With this latest publication, and his three previous books (1), Gareth Rees is building up a body of work that represents an alternative vision of Britain: a vision that reveals the fantastical that lies beneath the mundane. Unofficial Britain takes us on a journey through this island and embraces the kind of things we encounter every day, motorways, council houses, multi-storey car park, pylons and disused factories, but below the surface he reveals a seething cauldron of the decidedly weird.

In some ways Unofficial Britain is Rees’s most unrelentingly strange book. Its language has none of the hallucinogenic flights of fancy of earlier works, such as Marshland. This latest book’s prose is, in fact, resolutely straightforward and is interwoven with much of Rees’s backstory, including his early life. His subject matter, however, is anything but straightforward and he succeeds in summoning up a Gothic vision of modern Britain.

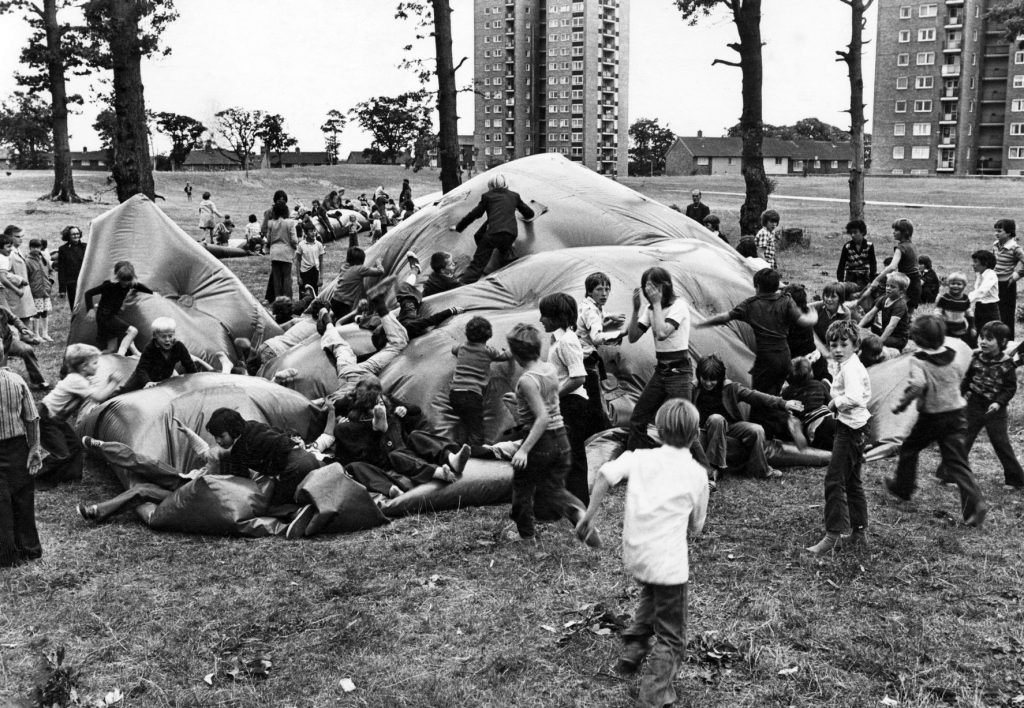

But this is not a Gothic of ruined castles, windswept moors, ill-fated heroines and tainted bloodlines. Rees’s Gothic is one rooted in the late twentieth century, an era whose time has come and gone but whose artefacts still dominate the landscape of present-day Britain. There is a folklore, a new mythology, Rees argues, that embraces tower blocks, motorways and the remnants of our heavy industries. These are narratives lodged in an analogue world of concrete and wires, an era fuelled by fossilised forests ripped from the earth.

Many of the places Rees visits comprise artefacts of the 1960s and 1970s, an era when Rees, and most of the contemporary influences he refers to in this book, were growing up. This is the world we were bequeathed, he suggests, and in many ways it is the one we live in still. In a nod perhaps towards Derrida, Rees also laments the world we were promised, but which never came to be. The 1960s vision of a modernism of technology, welfare and equality was strangled at birth, but it haunts us still, though it remains just a memory of a possibility.

Older folklore that grew up in our rural past, from a time when our very lives depended on the land and seasons, has somehow survived the industrial revolution and our transition into a largely urban society. This folklore survives in the form of ‘nursery rhymes, aphorisms, myths and legends of witches, boggarts, phantom dogs that roam the hills, and ghosts of grieving widows and long-dead soldiers’. But, Rees argues, it has been incorporated into new mythical narratives which were born in the industrial and post-industrial age:

What I learned on this journey is that everything changes and yet little does. Landscapes overlay landscapes, in ever-turning cycles. The flyover where a viaduct once stood. The Victorian workhouse that became a hospital. The steelworks on the site of a monastery. The burial cairn surrounded by a busy interchange. Motorway earthworks that rise alongside their Stone Age predecessors. The pretty bend on the river that became a dirty dockland then a ramshackle trading estate then an artist’s hub then an estate of luxury waterside high-rises. After each new manifestation replaces the old, it too becomes worn, decayed and saturated with nostalgia, to the point where some mourn its passing as much as others once lamented its coming. So the circle turns.

Unofficial Britain is a powerful and convincing contribution to this new mythology and should be required reading in every motorway service station coffee shop up and down this land. By way of full disclosure, I should also mention that a piece I wrote for the Unofficial Britain website about the Valley Works in Flintshire is featured in the book, together with subsequent conversations Gareth and I had about its history and a walk we both took around the perimeter of the disused works. This is the first time I have, knowingly, been a character in someone else’s book!

Unofficial Britain: Journeys Through Unexpected Places by Gareth E Rees (Elliott & Thompson, 2020)

(1) Marshland (Influx Press, 2013); The Stone Tide (Influx Press, 2018); Car Park Life (Influx Press, 2019)