Damp, clinging blanket

Icy wheedling fingers

Into every crevice and crack

The trees a hazy, spectral vision

Winter-breathed image upon smoked glass slide

Damp, clinging blanket

Icy wheedling fingers

Into every crevice and crack

The trees a hazy, spectral vision

Winter-breathed image upon smoked glass slide

The Croft Peace Garden is a small parcel of land in Holt Street, Wrexham. It is built on ground that was formerly a burial site for members of the Society of Friends (Quakers). In 1963 the site was gifted to the local authority in exchange a piece land nearby in Holt Road where a new Friends’ meeting house was built.

A Friends congregation was first established in Wrexham in 1661 and meetings were held in a house they hired. In 1708 they purchased premises in Holt Street to be used as a meeting house and burial ground. The Friends ceased meeting in Holt Street in the mid-eighteenth century and by 1800 the old meeting house had been demolished. The burial ground, however, remained in use.

Today the Peace Garden is a small, green oasis of trees, shrubs and grass in the centre of town. Up until 2002 it was a regular haunt for the town’s outdoor drinkers, but that year the garden became part of the town centre alcohol exclusion zone and the drinkers had to move elsewhere.

Today the Peace Garden is a small, green oasis of trees, shrubs and grass in the centre of town. Up until 2002 it was a regular haunt for the town’s outdoor drinkers, but that year the garden became part of the town centre alcohol exclusion zone and the drinkers had to move elsewhere.

When I visited the garden on a dry, bright January morning the place was completely deserted. Perhaps the lack of any seats or benches makes taking time-out in the Peace Garden a difficult proposition. A sleeping bag and bivi behind one the trees was evidence of some poor soul sleeping rough the previous evening on one of the coldest nights of the winter. In Britain, in 2019.

When I visited the garden on a dry, bright January morning the place was completely deserted. Perhaps the lack of any seats or benches makes taking time-out in the Peace Garden a difficult proposition. A sleeping bag and bivi behind one the trees was evidence of some poor soul sleeping rough the previous evening on one of the coldest nights of the winter. In Britain, in 2019.

The Croft Peace Garden is still occasionally used for peace-related events such as this one in 2007.

We live in a stocking which is in the process of being turned inside out, without our ever knowing for sure to what phase of the process our moment of consciousness corresponds.

Vladimir Nabokov, Bend Sinister

He especially liked the underpass and the way it took him from one side of the main road to the other. Straight down the slope on one side and then a long stretch of passageway under the road, with the traffic rumbling overhead, before he reached the ramp on the other side and emerged into the daylight.

But if you concentrated very hard as you approached the end of the tunnel, screwing up your eyes and letting them drift out of focus, you could sometimes catch the passageway unawares and manage to make a left turn at its end where normally there was only the slope straight ahead.

That was how he accessed the steps on the left. He called it his sinister turn and always experienced a slight lurch in his stomach as he ascended the staircase. At the top you reached… nowhere, just a patch of scrubby ground with grass and trees.

If you looked above the trees you could see the rooftops and familiar skyline of the town, but there was no way out of this small, enclosed area, other than back down the steps by which he had arrived.

He never met anyone else in this place, though the odd can and wrapper on the ground suggested there had been other visitors. If you listened hard you could just about hear birdsong, traffic and the urban hum, but all seemed distant as if projected through an old-style telephone line.

He never met anyone else in this place, though the odd can and wrapper on the ground suggested there had been other visitors. If you listened hard you could just about hear birdsong, traffic and the urban hum, but all seemed distant as if projected through an old-style telephone line.

He never lingered long when he came here; this place was peaceful, but not in a pleasant way. Soon a feeling would rise in his chest and start to become unbearable. Immediately he felt this way he would turn and make for the steps; relieved, every time, to find they were still there.

He never lingered long when he came here; this place was peaceful, but not in a pleasant way. Soon a feeling would rise in his chest and start to become unbearable. Immediately he felt this way he would turn and make for the steps; relieved, every time, to find they were still there.

Essex, the Fens, Suffolk, Sussex and London; 2018 has been a good year for books in which the landscape, be it the countryside or city streets, plays a prominent role. There is no such thing as psychogeographic fiction. However, there are novels in which the natural or built environment leaves an indelible mark upon the writer’s characters. Books in which the accumulated echoes of the past, of those who lived and died in a particular location, generation upon generation, make their presence known to those who live there today. Some such books are conscious explorations of the influence of landscape: the works of Iain Sinclair, Rebecca Solnit and W.G. Sebald come to mind. In other books I’m thinking about, most others in fact, the landscape plays the role of a major character inhabiting the narrative structure of the writer’s world.

One thing that strikes me when I consider the books I have read in 2018 is the preponderance of female writers. This was, in part, conscious and deliberate: I feel compelled to listen to those voices that were once drowned out. Pat Barker’s feminist reimagining of The Iliad is a perfect example of this. But it is also representational of the fact that more and more female writers are taking their creative imagining out into the fields and streets and claiming that territory as their own, or at least as much as it is that of male writers.

The flâneuse is alive and well: Lauren Elkin, on foot and in words, explored this concept in 2016. Several years before, Karen Van Godtsenhoven, now curator at the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Costume Institute in New York, covered much of the same ground in her dissertation. My own interest in the idea of the flâneuse goes back even further: my dissertation for my English MA looked at this concept in the works of Virginia Woolf and Dorothy Richardson. Some of this exploration has resurfaced within this blog here, here and here.

There is a common misconception, even among people who are reasonably well-read and should know better, that it is only men who write about landscape. From Thomas Hardy to Iain Sinclair the literature of rural and urban topography is dominated by men, or so the argument goes. Women, if one is to stretch the argument ever more thinly, only write about interiors; the interior of the home and the heart. This, of course, is nonsense, and twentieth-century writers such as Mary Austin, Nan Shepherd and Annie Dinnard provide ample evidence of this point. Casting one’s net further back to include the preceding century, a time before any legislation promoting female emancipation, Emily Brontë made the Yorkshire Moors a powerful, brooding presence in Wuthering Heights and George Eliot’s Middlemarch provided a vivid evocation of provincial England.

So here is Psychogeographic Review’s list of recommendations for the year:

The Silence of the Girls – Pat Barker (Hamish Hamilton, 2018)

All Among the Barley – Melissa Harrison (Bloomsbury, 2018)

The Pisces – Melissa Broder (Bloomsbury, 2018)

The Great Level – Stella Tillyard (Chatto & Windus, 2018)

A View of the Empire at Sunset – Caryl Phillips (Vintage, 2018)

The Gloaming – Kirsty Logan (Harvill Secker, 2018)

Girl Balancing and Other Stories – Helen Dunmore (Hutchinson, 2018)

Crudo – Olivia Laing (Picador, 2018)

Modern Nature: The Journals of Derek Jarman, 1989 – 1990 – Derek Jarman (Vintage Classics, 2018)

The Pisces – Melissa Broder (Bloomsbury, 2018)

The Tunnel Through Time: A New Route for an Old London Journey – Gillian Tindall (Chatto & Windus, 2018)

Bird Cottage – Eva Meijer (Pushkin Press, 2018)

Trans-Europe Express: Tours of a Lost Continent – Owen Hatherley (Allen Lane, 2018)

The Immeasurable World: Journeys in Desert Places – William Atkins (Faber, 2018)

Ground Work: Writings on Places and People – ed. Tim Dee (Jonathan Cape, 2018)

Arkady – Patrick Langley (Fitzcarraldo, 2018)

Ghost Wall – Sarah Moss (Granta, 2018)

The Stone Tide – Gareth E Rees (Influx Press, 2018)

Milkman – Anna Burns (Faber, 2018)

Low Country: Brexit on the Essex Coast – Tom Bolton (Penned in the Margins, 2018)

Of course there are always other books to be read. Here are some of those not published in 2018, but which were read by this blog writer during the year. In this regard I’d like to recommend a literary podcast I’ve discovered during the course of this year which has become a firm favourite. Backlisted is hosted by John Mitchinson (publisher at Unbound) and Andy Miller (author of The Year of Reading Dangerously) and aims to give ‘new life to old books’.

Walter Benjamin: A Critical Life – Howard Eiland and Michael W Jennings (Harvard, 2014)

The Outrun – Amy Liptrot (Canongate, 2016)

Elmet – Fiona Mozley (Hodder & Stoughton, 2017)

Wise Blood – Flannery O’Connor (Faber & Faber, 1952)

A Good Man is Hard to Find – Flannery O’Connor (Faber Modern Classics, 1955)

The Sense of an Ending – Julian Barnes (vintage, 2011)

Alma Cogan – Gordon Burn (Secker & Warburg, 1991)

My Favourite London Devils – Iain Sinclair (Tangerine Press, 2016)

The Loney – Andrew Michael Hurley (John Murray, 2015)

Reservoir 13 – Jon McGregor (Harper Collins, 2017)

Two Serious Ladies – Jane Bowles (Alfred A Knopf, 1943)

Watling Street – John Higgs (Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 2017)

The Tiger in the Smoke – Margery Allingham (Penguin, 1952)

He Died With His Eyes Open – Derek Raymond (Secker & Warburg, 1984)

Look at Me – Anita Brookner (Penguin, 1983)

A State of Denmark – Derek Raymond (Serpent’s Tail, 1970)

Beyond Black – Hilary Mantel (Fourth Estate, 1975)

One Man & His Plot – Michael Leapman (Faber & Faber, 1975)

History of Britain in Maps – Philip Parker (Harper Collins, 2017)

So Long, See You Tomorrow – William Maxwell (Vintage, 1980)

The Goldfinch – Donna Tartt (Abacus, 2013)

The Underground Railroad – Colson Whitehead (Fleet, 2016)

Books

Crudo – Olivia Laing (Picador, 2018)

Kathy Acker did not die in 1997. She, or someone very much like her, lives on to witness the recent rise of right-leaning populism in Europe and the United States and, when we meet her in 2017, is on the verge of getting married to an older, somewhat conventional man.

This is the premise of Olivia Laing’s latest book, but it is much more than a speculative fiction about where two decades more life might have taken Kathy Acker. Like her previous works, Crudo is a book which Olivia Laing inhabits and which provides her with a vehicle to explore elements of her own life and experience. She recreates the rawness and urgency of the best of Kathy Acker’s work and adds her own style, wit and story-telling powers to this heady mix.

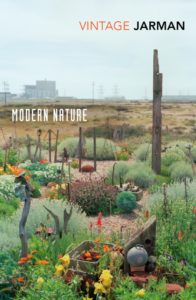

Modern Nature: The Journals of Derek Jarman, 1989 – 1990 – Derek Jarman (Vintage Classics, 2018)

The late 1980s were a bleak time in this country. Margaret Thatcher’s economic policies were ripping out manufacturing jobs and devasting working-class communities whilst new legislation, enforced by police power, was emasculating the trade unions. HIV/AIDS was killing people every day, yet Section 28 prevented young people from asking questions about their sexuality and teachers from providing them with answers.  This newly reissued journal covers this period in Derek Jarman’s life and is framed by his efforts to create a garden in the unpromising soil of his cottage near the sea in Dungeness. His sand and shingle garden sits in the shadow of a nuclear power station and is assailed by wind and spray. And yet, in this most unpromising of locations, and with his health steadily failing, he creates a place of beauty. Jarman continues to make films in this period, and gives the reader fascinating insights into his working methods.

This newly reissued journal covers this period in Derek Jarman’s life and is framed by his efforts to create a garden in the unpromising soil of his cottage near the sea in Dungeness. His sand and shingle garden sits in the shadow of a nuclear power station and is assailed by wind and spray. And yet, in this most unpromising of locations, and with his health steadily failing, he creates a place of beauty. Jarman continues to make films in this period, and gives the reader fascinating insights into his working methods.  While throughout the journal he rails against the cruelty of attitudes towards gay people and others affected by HIV/AIDS. Modern Nature is a beautiful, compelling and angry work, and this edition has the added bonus of superb introduction by Olivia Laing.

While throughout the journal he rails against the cruelty of attitudes towards gay people and others affected by HIV/AIDS. Modern Nature is a beautiful, compelling and angry work, and this edition has the added bonus of superb introduction by Olivia Laing.

Music

Shildam Hall Tapes – A Year in the Country (2018)

Shildam Hall, we are led to believe, is a manor house in rural England and in the late-1960s it was the setting for a film that was never completed. The film became mired in alleged drug use and occult practices and all funding was withdrawn. Sadly, the script and all footage have since disappeared without trace.

Shildam Hall Tapes is an imagined soundtrack for the film and includes tracks by several artists who have featured on other A Year in the Country releases. Indeed, the collective is steadily building up a body of work that presents an alternative view of rural Britain. A Year in the Country’s lens both distorts and illuminates its subject matter, but the project’s output is consistently fascinating.

Inspirational Talks – HMS Morris (2018)

Other reviewers have compared the work of HMS Morris with the early psych-pop of Gruff Rhys and the band themselves cite Syd Barrett as a major influence.  But with this release the Cardiff three-piece show that they have evolved into a unit that creates a sound which is very much their own. Inspirational Talks features tracks in both English and the Welsh and lead singer/guitarist Heledd Watkins showcases her perfect pop voice in both languages.

But with this release the Cardiff three-piece show that they have evolved into a unit that creates a sound which is very much their own. Inspirational Talks features tracks in both English and the Welsh and lead singer/guitarist Heledd Watkins showcases her perfect pop voice in both languages.

But, using the format of the pop song as a launch pad, HMS Morris head out into realms of synth-led experimentation, particularly with the stand-out tracks Cyrff and (On Our Way From) Earth.

Film

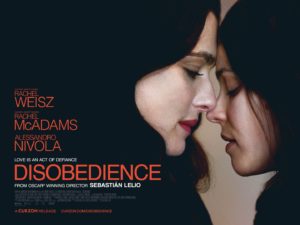

Disobedience – Sebastián Lelio (2018)

I watched Disobedience because it was an adaptation of the Naomi Alderman novel, which I enjoyed when I read it in 2006.  In my experience, films of well-loved novels are not always a success, but I’m pleased to say that in this case I was not disappointed. Sebastián Lelio, as a male Chilean-Argentine director is not perhaps the obvious choice to direct this story of a lesbian love affair within the North London orthodox Jewish community.

In my experience, films of well-loved novels are not always a success, but I’m pleased to say that in this case I was not disappointed. Sebastián Lelio, as a male Chilean-Argentine director is not perhaps the obvious choice to direct this story of a lesbian love affair within the North London orthodox Jewish community.

However, he handles his subject matter with grace and sensitivity, helped, no doubt, by Alderman’s role as an adviser to the production process. The three leads, Rachel Weisz, Rachel McAdams and Alessandro Nivola also make a major contribution to the success of this adaptation.

The Bookshop – Isabel Coixet (2017)

The Bookshop is an odd somewhat sombre film set in a Suffolk seaside town in the 1950s. Florence Green (played by Emily Mortimer) opens a bookshop in the town and faces opposition from several of the locals.  The England we are presented with by the Catalan film-maker, Isabel Coixet, is a deeply strange place. But perhaps it is only through the eyes of an outsider that we can gain new insights and learn new truths about a time and a place we thought we already knew.

The England we are presented with by the Catalan film-maker, Isabel Coixet, is a deeply strange place. But perhaps it is only through the eyes of an outsider that we can gain new insights and learn new truths about a time and a place we thought we already knew.

The atmosphere of Coixet’s film puts me in mind of a snippet of lyrics from Pink Floyd’s Time: ‘Hanging on in quiet desperation is the English way’. Emily Mortimer captures this mood beautifully and Bill Nighy, as one might expect, is excellent as her eccentric local supporter.

Books

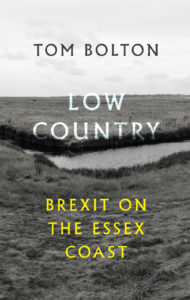

Low Country: Brexit on the Essex Coast – Tom Bolton (Penned in the Margins, 2018)

Think of Essex and what comes to mind? For many it will be Norman Tebbit, Teddy Taylor and that peculiarly Essex-led brand of working-class Toryism that brought Thatcher to power in 1979 and sustained her through the 1980s. Or maybe it’s the unbridled aspiration, conspicuous consumption and cheerful anti-intellectualism of Essex Girl, Essex Man and TOWIE? But Essex, we should remember, has a proud history of dissent and radical politics: it was the seedbed of the Peasants’ Revolt and, since the nineteenth century, it has been home to a number of experimental communities that sought to reject capitalism and conventional notions of patriarchy.

Tom Bolton sets out to explore this history by walking the entire length of the Essex coast; and, as we learn, it is a very long coastline, one that meanders drunkenly through creeks, mudflats and low-lying islands. But for Bolton, and his walking companion Jo Healy, the quest is not so much about history but about the present day. Geographically close to London, but far-removed in so many other ways, Essex is at once a point of access for those wishing to enter England peacefully and along its coast we are frequently reminded of its role as a key front line of defence against those who wished to invade. Crucially, the county was one of the heartlands of the pro-Brexit campaign with some 62.3% of those who took part in the 2016 referendum voting to leave the EU.

Tom Bolton sets out to explore this history by walking the entire length of the Essex coast; and, as we learn, it is a very long coastline, one that meanders drunkenly through creeks, mudflats and low-lying islands. But for Bolton, and his walking companion Jo Healy, the quest is not so much about history but about the present day. Geographically close to London, but far-removed in so many other ways, Essex is at once a point of access for those wishing to enter England peacefully and along its coast we are frequently reminded of its role as a key front line of defence against those who wished to invade. Crucially, the county was one of the heartlands of the pro-Brexit campaign with some 62.3% of those who took part in the 2016 referendum voting to leave the EU.

Bolton’s walk takes him from Purfleet on the Thames Estuary to Manningtree on the Suffolk border. But his odyssey is not unbroken: work commitments and the practical limitations of public transport mean that the journey needs to be made in stages and on weekends often weeks apart. But this does not seem to affect the continuity and power of Bolton’s narrative, indeed there is a hypnotic quality to his landscape descriptions in this book; something to do, perhaps, with the way that the writer conveys how it seems the three elements of the coastline of Essex, sky, sea and sand, constantly coalesce at the vanishing point forming an unreachable fourth place.

We pass through mudflats and along crumbling sea walls, taking in retail parks, sewage outfalls and coastal forts. At a line of concrete tank obstacles just beyond Manningtree we reach Suffolk and the end of Bolton’s journey.

And as he walks Bolton mediates on Essex past and present. It is a Janus-faced county, divided in its nature. Divided, Bolton seems to suggest, in much the same way as Britain as a whole has turned in upon itself.

(Low Country: Brexit on the Essex Coast is launched on 30 October 2018 and my review copy was kindly provided by the publisher)

Trans-Europe Express: Tours of a Lost Continent – Owen Hatherley (Allen Lane, 2018)

I first came across Owen Hatherley’s writings on architecture, society and politics in 2009. In Militant Modernism he wrote scathingly about the British take on modernism with his starting point being his own upbringing on an estate in Southampton, a place that was ‘impoverished, violent and desolate.’ Trans-Europe Express: Tours of a Lost Continent is an anthology that attempts to take a much broader scope, but once more he starts his story in his home city of Southampton.

A few days after the Brexit referendum he returned home and ended up having a heated exchange with his mother over the result. She supported the leave campaign from an old-style socialist perspective, whereas Hatherley voted to remain. His reasons for wanting to stay in the EU, however, were primarily architectural rather than economic or political. Hatherley associates Europe, we learn, with good architecture, of both the traditional and modern variety, whereas so much of the architecture of Britain, he argues, is blighted by the primacy of the economic bottom line.

Trans-Europe Express is not a systematic review of European architecture, but more an anthology of essays based on a series of journeys through the continent. It is also a lament for the way that Britain’s few brave attempts at European-style communal cityscapes has given way to our more ubiquitous privatisation of public spaces. Hatherley presents the cities of Łódź, Hamburg and Rotterdam as models, but also as lost opportunities.

Trans-Europe Express is not a systematic review of European architecture, but more an anthology of essays based on a series of journeys through the continent. It is also a lament for the way that Britain’s few brave attempts at European-style communal cityscapes has given way to our more ubiquitous privatisation of public spaces. Hatherley presents the cities of Łódź, Hamburg and Rotterdam as models, but also as lost opportunities.

Music

Audio Albion – A Year in the Country (2018)

A Year in the Country is an ongoing project exploring the mythical underbelly of Britian’s rural topography. Through music, writing and visual art we are invited to dream, and in doing so take a deep dive into an ‘otherly pastoralism’.

Blending music and field recordings Audio Albion maps out the countryside and edgelands of this island and immerses us in the myths and legends that inhabit even the most mundane landscapes. The album comprises the work of fifteen different artists. But this is not a collection of tracks: it is a carefully constructed aural journey.

Blending music and field recordings Audio Albion maps out the countryside and edgelands of this island and immerses us in the myths and legends that inhabit even the most mundane landscapes. The album comprises the work of fifteen different artists. But this is not a collection of tracks: it is a carefully constructed aural journey.

Joy’s Reflection is Sorrow – Sharron Kraus (Nightshade, 2018)

Sweet and sour, light and shade, happiness and despair, Joy’s Reflection is Sorrow is underpinned, as its cover illustration suggests, by a Jungian shadow-self and a mix of contrasting styles to match Kraus’s sweeping gamut of emotional reflections.

The ethereal opener My Danger gives way to the rockier, anthemic Figs and Flowers. The Man Who Says Goodbye follows with a joyous melody and lush instrumentation whereas Joy’s Reflection is Sorrow returns us inevitably to a more introspective mood. Sorrow’s Arrow and Secrets are achingly poignant and When Darkness Falls and Death and I are both as dark as their titles suggest.

The ethereal opener My Danger gives way to the rockier, anthemic Figs and Flowers. The Man Who Says Goodbye follows with a joyous melody and lush instrumentation whereas Joy’s Reflection is Sorrow returns us inevitably to a more introspective mood. Sorrow’s Arrow and Secrets are achingly poignant and When Darkness Falls and Death and I are both as dark as their titles suggest.

Kraus’s songs are subtle and heart-felt and her influences are clearly very eclectic. With the musicians she has gathered around her for this release and with the quality of her own performance Sharron Kraus is clearly an artist who has reached her musical prime. Long may it last.

Film

Arcadia – Paul Wright (2018)

Arcadia could so easily have ended up as nothing more than a cobbled-together and vaguely diverting compilation of archive footage of the British countryside; something that might find a comfortable home in the early evening schedule of BBC Four. Instead, with his inspired selection of footage and skilled editing, together with an atmospheric soundtrack by Adrian Utley and Will Gregory, Paul Wright has produced a folk-horror classic. A film that is all the more disturbing because it is not a work of fiction.

Arcadia could so easily have ended up as nothing more than a cobbled-together and vaguely diverting compilation of archive footage of the British countryside; something that might find a comfortable home in the early evening schedule of BBC Four. Instead, with his inspired selection of footage and skilled editing, together with an atmospheric soundtrack by Adrian Utley and Will Gregory, Paul Wright has produced a folk-horror classic. A film that is all the more disturbing because it is not a work of fiction.

Watching Arcadia one is left with the impression than nothing but a thin veneer of rational modernity covers up the essentially pagan nature of life in rural Britain. Customs, rituals, protests and the daily routines of rural life are all recontextualised through Wright’s lens into a film that is decidedly eerie in its effect. Viewing this montage of images and voices in 2018, one is left with the uneasy feeling that our current Brexit woes are the revenge of deep rural Britain against a metropolitan-led nation.

You Were Never Really Here – Lynne Ramsay (2017)

Lynne Ramsay has directed some of the most innovative and compelling British films of the past two decades, most notably Ratcatcher and Morvern Callar. You Were Never Really Here is her first feature film since 2011’s We Need to Talk About Kevin and received awards at the 2017 Cannes Film Festival for Joaquin Phoenix’s central performance and Ramsay’s screenplay.

Lynne Ramsay has directed some of the most innovative and compelling British films of the past two decades, most notably Ratcatcher and Morvern Callar. You Were Never Really Here is her first feature film since 2011’s We Need to Talk About Kevin and received awards at the 2017 Cannes Film Festival for Joaquin Phoenix’s central performance and Ramsay’s screenplay.

Released in the UK this year You Were Never Really Here is a taut psychological thriller and features a standout musical score by Radiohead’s Jonny Greenwood. Phoenix is excellent as a hitman unwittingly caught up in a web of political corruption and human trafficking. But it is Ramsay’s tight, uncompromising direction that drives this film forward.

Why can’t I write something that would awake the dead? That pursuit is what burns most deeply.

Patti Smith Just Kids

The streets haunt you, just as echoes of you haunt them. You walk past the bell foundry, an insinuation of holy smoke and sonorous alchemy, and into Fieldgate Street. Drunken nights walking home arms around shoulders, your talk bubbling out excitedly with butterfly ideas and suddenly-clear insights, all forgotten by the morning. You tell Sarah about the book on relativity that you just read: words, unmediated and ill-understood tumble from your mouth and vanish like soap bubbles in the night air. She feels sorry for Nixon over yesterday’s resignation, she says, despite everything he’s done. He’s just a flawed human being like the rest of us. You come to the ghost-signed shop fronts at the turning into Settles Street. Store fronts that are never open, whatever time of day you pass, yet often they echo with the sound of voices within. On the next corner a fruit and vegetable distributor, its doors always shut fast, yet still the redolent smell of ripe onions. No longer able to resist, your eyes are drawn to the other side of the road, a monolith of red brick, the fingers of its Gothic corner towers scratching at the sulphurous sky, a low canopy of purple and grey. Rowton House, Jack London’s ‘monster doss house’, stares back at you, daring you to blink. Men queue to be allowed in: a still, silent line, an air of resignation hanging over them like the aroma of an unbidden fart. Meanwhile others, occasional and individual, burst out through the doss house doors, desperate to shake off its fetid air. Here and in the surrounding streets émigré Bolsheviks still debate with Mensheviks and, smiling, secretly plot their moment of vengeance each upon the other. Silent yet wakeful, Joseph Stalin lies in his bunk listening to the snores of Litvinov in the next cubicle. While before you on the street, his head bowed, the boots of a passing dosser beat a loose-soled tattoo against the greasy paving slabs.

This is a short extract from an extended deep memory trip by Bobby Seal with pictures of Whitechapel in the 1970s by David Hoffman. The full piece and photographs can be seen at Unofficial Britian.

I have to confess that when I first heard that Gareth Rees was moving from his home in East London to the Sussex coastal resort of Hastings it seemed to me odd for a relatively young writer to be forsaking the vibrant metropolitan cultural hub in order to settle in a quiet provincial backwater. Particularly so when Rees had just spent several years developing Hackney Marshes and the River Lea as his personal genius loci and the setting for his first novel, Marshland. However, while Hastings is very much part of England’s provincial outlands, one thing we learn from The Stone Tide is that it is a decidedly unquiet place.

The Hastings of this, Gareth Rees’s second book, is haunted by ghosts: emanations of the town’s past, present and, indeed, its precognitive future. Perhaps this is hardly surprising given that Aleister Crowley, the so-called Great Beast, spent his final days in Hastings and ever since the place has attracted a variety of mystics, occultists, visionaries and shysters. But Rees is also haunted by the ghosts that he brings with him, memories and presences that take root and grow in the fertile loam of Hastings’ psychic vortex.

The Stone Tide is peopled with a cast of strange and compelling characters, past and present. Charles Dawson of the infamous Piltdown Man hoax rubs shoulders with Sir Arthur Conan Doyle and Teilhard de Chardin, the Jesuit priest who predicted the World Wide Web. Robert Tressell, one-time Hastings resident and author of the Ragged Trousered Philanthropists gets a mention, as does Rod Hull and Emu. John Logie Baird lived here for a time, arriving in 1923 to recover from a period of ill health. Whilst in the town he continued to experiment with the transmission of moving images. There is little evidence that Baird and Aleister Crowley ever met, but in Gareth Rees’s alternative history they do. Crowley confronts Baird on Hastings seafront accusing him of stealing his transmission idea, corrupting it from a medium to accumulate and raise human consciousness to another level into a device for mere entertainment:

Unbeknown to you, this technology was being developed in secret by adepts, like Promethean fire, for the liberation of mankind….if only your greedy little mind could imagine such a thing – to see across dimensions, to commune with the spirits, to wield influence in the universe!

The Stone Tide starts off in conventional enough fashion. Burdened by debts Rees, his wife Emily and their two young daughters move from London to a large, end-of-terrace Victorian house on the south coast. The house has potential but is badly in need of renovation, so the couple have the idea of gradually doing it up into their idyllic family home at the same time as Emily pursues her burgeoning career in digital marketing and Rees works on his second novel.

In a parallel universe this book could be the simple tale of a shiny, happy couple transforming a wreck of an old house into their shiny, happy new home: the dross of dereliction transmuted into designer chic, no doubt with numerous asides about local characters and colour. But from their first evening in Hastings we realise this is not going to be the case. It is even more run down and unloved than they remember it from their first viewing:

Above the front door, a cracked stone lintel was the house’s broken heart. Its subsiding interior had the wonk of an eighteenth-century galleon. There was an oppressive gravity to the place, as if it could no longer bear the weight of its own existence.

The house is peopled with odd noises and distant voices. It seems to be alive with creatures revelling in its decay: swarms of flies and rats and one particularly evil-seeming herring gull. Everywhere there is dust: the accumulated residue of decades, a shedding of generations of human skin. They clean up one lot of dust and more appears by the next day.

I enjoyed Marshland, Gareth Rees’s previous book, but this is something entirely different. Whereas his earlier novel sat comfortably in the oeuvre of London psychogeographic writing that has become so ubiquitous in the last decade or so, The Stone Tide, although clearly from the same writer, is instead a work of breathtaking originality. If Marshland was Gareth Rees’s With the Beatles novel, then The Stone Tide is definitely his Rubber Soul project. In other words, he has progressed from the competently entertaining to something strikingly new and exciting. I look forward to his Sergeant Pepper moment in the not too distant future.

Nothing is solid in The Stone Tide: everything is permeable and subject to the ravages of time and nature. Rees’s grip on reality begins to falter, his marriage shows cracks and their new home continues to crumble and decay. Even the very rock upon which Hastings is built proves to be neither solid nor permanent; the actions of tide and river cause whole chunks to fall into the sea. Indeed, the sea is ever present; it is vast, brooding and threatening and is a constant reminder to Rees that it was beside this same sea, in another part of this island, that his best friend died two decades earlier.

The only place to go was the sea. The indifferent, angry, calm, fucked-up sea. The sea that began life on earth. The sea that would finish us all off. The sea that took Mike then brought him back again.

But it is not just the crumbling cliffs of Hastings where a rift is opened up, the linear flow of time itself seems to have been disturbed. When he arrives in Hastings Gareth Rees seems to be secure on the rock upon which his life is built: his sense of himself, his marriage, family and his career, all of which seem to be going well. Even the greatest sadness of his life, the tragic loss of his best friend, Mike, some twenty years before, seems to be something that Rees has now dealt with, something with which he has come to terms. But in Hastings he assailed by forces which open-up the crusted wound of his grief.

Rees writes with painful honesty:

Our family was falling apart and I had failed to see it. I’d let it happen. I’d walked away from the truth.

There is much sorrow in this book, but its overall effect is not entirely bleak or self-indulgent; the sadness at the heart of The Stone Tide is leavened by the verve of Rees’s prose and his self-deprecating humour. Amid the despair and aching loss in this book there is hope and a determination to carry on:

Humankind is not locked into some ordained destiny. Consciousness is a force as powerful as time, strong as gravity. It moves through the universe, through the earth, through animals, vegetation and rocks. It mutates and evolves. It creates its own reality. The human mind, with its extraordinary imagination and capacity for invention, has unlimited potential, both to create catastrophe and avert it.

Rees worries throughout the time covered by this book if he will ever complete his current writing project and, if he does, whether it will be any good. Clearly, he does finish it and, equally clearly, it is indeed very good.

The Stone Tide: Adventures at the End of the World is available to pre-order from the publishers, Influx Press

A collection of seasonal reading loosely connected by the themes of landscape, time and memory…

The Last London: True Fictions from an Unreal City – Iain Sinclair

The Last London: True Fictions from an Unreal City – Iain Sinclair

This is the eighteenth and supposedly final chapter of Iain Sinclair’s London novel. Or it is if, like me, you view Sinclair’s London writings as a single body of work. From the moment Sinclair arrived in London in the late-1960s he walked. He traversed the city’s streets, footpaths and forgotten spaces creating in his mind an ever-evolving map of the place London occupied in time and space. Sinclair has explored the occult significance of the alignment of Hawksmoor’s churches in Lud Heat, circled the city’s outer cordon in London Orbital and traced John Clare’s escape route from the city in Edge of the Orison. In these and his other London writings he has created a body of work that has altered the way we look at and write about London and, indeed, cities in general. With a heavily-weighted allusion to Eliot, London is presented as an ‘unreal city’. The Last London is a collection of essays each of which has its conception in a series of walks through the city but most of which then branch out into a host of other reflections and speculations. The collection has the tone of an elegy: a marking of something coming to an end. Indeed, Sinclair has already returned to his South Wales roots with 2015’s Black Apples of Gower and has placed one foot outside of London by buying a flat in Hastings. But for now he remains a resident of Hackney and, I suspect, The Last London will not be his final word on the capital.

and write about London and, indeed, cities in general. With a heavily-weighted allusion to Eliot, London is presented as an ‘unreal city’. The Last London is a collection of essays each of which has its conception in a series of walks through the city but most of which then branch out into a host of other reflections and speculations. The collection has the tone of an elegy: a marking of something coming to an end. Indeed, Sinclair has already returned to his South Wales roots with 2015’s Black Apples of Gower and has placed one foot outside of London by buying a flat in Hastings. But for now he remains a resident of Hackney and, I suspect, The Last London will not be his final word on the capital.

Devil’s Day – Andrew Michael Hurley

Devil’s Day – Andrew Michael Hurley

Andrew Michael Hurley is the author of The Loney, a surprise best-seller from 2014 and winner of the Costa first novel award. As with his previous book, Devil’s Day risks being saddled with the genre fiction label ‘British folk-horror’, which is a little unfair to a writer of Hurley’s originality. The Endlands is a remote corner of upland Lancashire. Farming families struggle for generation after generation, trying to eke out a living from the unforgiving land. Yet somehow it all works: the land always provides and its inhabitants live in balance with it and with each other. But something else lurks beneath the surface. It is to this wind-blasted corner of the north that John Pentecost, having given up a teaching job in the south, brings his reluctant, pregnant wife. They encounter suspicion and have to come to terms with loyalties based on blood ties and tradition, all set within a landscape mediated by ageless ritual. Throughout it all Hurley successfully nurtures a growing sense of unease and deep-rooted evil.

other. But something else lurks beneath the surface. It is to this wind-blasted corner of the north that John Pentecost, having given up a teaching job in the south, brings his reluctant, pregnant wife. They encounter suspicion and have to come to terms with loyalties based on blood ties and tradition, all set within a landscape mediated by ageless ritual. Throughout it all Hurley successfully nurtures a growing sense of unease and deep-rooted evil.

Linescapes: Remapping and Reconnecting Britain’s Fragmented Wildlife – Hugh Warwick

Linescapes: Remapping and Reconnecting Britain’s Fragmented Wildlife – Hugh Warwick

Since these islands were first inhabited, human beings have traced lines across the landscape: hedgerows, dry stone walls, green lanes, drovers’ tracks, corpse roads, canals, railways and ley lines, all have placed their mark upon the land. For thousands of years humans have drawn lines across the landscape, destroying wildlife habitats in some cases but offering new opportunities to some species in others. Britain’s lines upon the landscape were comprehensively surveyed by Alfred Watkins as long ago as the 1920s with his seminal The Old Straight Track and again by others on many occasions since, including Robert Macfarlane’s recent The Old Ways. But along with the romance of the ancient trackway there was the warning of humankind’s damage to the land. Henry Williamson’s The Vanishing Hedgerows, a BBC film in 1972, documented the devastating effect mechanised farming, which required ancient hedges to be grubbed up to create giant fields, was having on the habitat of countless species of flora and fauna. Warwick provides a first-hand survey of Britain’s linescapes. Whilst the human-made marks on our landscape cannot be erased, he argues, opportunities to rewild and reconnect the countryside using these lines abound. He gives examples, both planned and accidental, of places where nature has been able to reassert herself and makes compelling proposals for how we might encourage this process.

Macfarlane’s recent The Old Ways. But along with the romance of the ancient trackway there was the warning of humankind’s damage to the land. Henry Williamson’s The Vanishing Hedgerows, a BBC film in 1972, documented the devastating effect mechanised farming, which required ancient hedges to be grubbed up to create giant fields, was having on the habitat of countless species of flora and fauna. Warwick provides a first-hand survey of Britain’s linescapes. Whilst the human-made marks on our landscape cannot be erased, he argues, opportunities to rewild and reconnect the countryside using these lines abound. He gives examples, both planned and accidental, of places where nature has been able to reassert herself and makes compelling proposals for how we might encourage this process.

Watling Street: Travels Through Britain and Its Ever-Present Past – John Higgs

Watling Street: Travels Through Britain and Its Ever-Present Past – John Higgs

One of the most ancient of Britain’s trackways was worn into being by the passage of human feet travelling back and forth from the cliffs of Dover across country to Anglesey. Dover has long been Britain’s point of contact with continental Europe and, since the Bronze age, Anglesey has been the site of mining for its rich copper and lead deposits as well as a sacred place in the Druidic tradition. The track was straightened by the Roman legions who also extended a branch eastwards from Chester to York. During the Roman occupation it became known as Watling Street. We can still trace Watling Street  today: it is shadowed by the A2, A5 and M6 toll road. But its presence is not just physical, argues Higgs. Watling Street, he suggests, has its own noosphere: a presence that is unique and palpable. The term noosphere was first coined by Pierre Teilhard de Chardin in 1922 to describe the realm of myth and tradition and its influence on the human mind. Higgs meets contemporary shamans, sages and other outcasts along the route of Watling Street and reminds us that the past, in both a physical and mythical sense, is always only just below the surface. Watling Street is part of the story of these islands and, Higgs argues, has the potential to inform our future.

today: it is shadowed by the A2, A5 and M6 toll road. But its presence is not just physical, argues Higgs. Watling Street, he suggests, has its own noosphere: a presence that is unique and palpable. The term noosphere was first coined by Pierre Teilhard de Chardin in 1922 to describe the realm of myth and tradition and its influence on the human mind. Higgs meets contemporary shamans, sages and other outcasts along the route of Watling Street and reminds us that the past, in both a physical and mythical sense, is always only just below the surface. Watling Street is part of the story of these islands and, Higgs argues, has the potential to inform our future.

Elmet is a Gothic-tinged slice of folk noir rooted in the landscape of the North of England, a land that, seen through Mozley’s eyes, is at once contemporary and mythical. The story is told from the point of view of 14-year old Daniel who lives with his older sister, Cathy, and their father, John, in a remote cottage in a wooded area of West Yorkshire, an area steeped in the myths of the ancient Brittonic kingdom of Elmet. John, known simply as Daddy, is a great brute of a man who makes his living with his fists. Cathy has been taught how to hunt and forage by her father while the gentler Daniel stays at home to look after their meagre, impoverished household. Elmet is a meditation on family, poverty, intolerance and the all-pervading power of memory. Above all it is a book that draws the reader into the brooding presence of an ancient landscape. Mozley’s prose is full of lyrical beauty and this, her first novel, rightly made it onto this year’s Man Booker shortlist.

taught how to hunt and forage by her father while the gentler Daniel stays at home to look after their meagre, impoverished household. Elmet is a meditation on family, poverty, intolerance and the all-pervading power of memory. Above all it is a book that draws the reader into the brooding presence of an ancient landscape. Mozley’s prose is full of lyrical beauty and this, her first novel, rightly made it onto this year’s Man Booker shortlist.

You Are Here: The Biography of a Moment – Matthew Watkins

You Are Here: The Biography of a Moment – Matthew Watkins

In the first and final second of forever, I thought of the long past that had led to now and never… never… never… never…

Robert Calvert: Ten Seconds of Forever

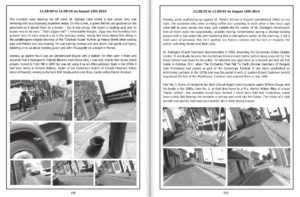

Matthew Watkins uses this quote as an epigraph to his You Are Here: The Biography of a Moment. On 30th December 1972 I see Bob Calvert and Hawkwind take to the stage at the Liverpool Stadium and perform their Space Ritual. I bare my chest and dance. Almost at the same moment, in Cambridge Massachusetts, Edward Lorenz delivers his Butterfly Effect paper to the 139th meeting of the American Association for the Advancement of Science. On the following day two leap seconds are added to the year, making 1972 the longest in human history. This may have very little to do with Watkins’ book, but it does help me to find a personal starting point for reviewing this satisfyingly strange volume. He describes You Are Here as ‘an accelerating history of Canterbury from the Big Bang to noon August 15th 2014’. It is, indeed, a book about time and place. The place is very small and specific: Canterbury in the county of Kent where Watkins currently lives and works. His temporal scope, however, is infinite: he encompasses the dawn of time right through to the (almost) present day. But what happens on 14th August 2014? The answer is small, specific and infinite, not to mention genuinely unsettling. Time is strange, we learn. It does not progress in a strictly linear fashion. Watkins is a mathematician and an exponent of the concept of retrocausality. And in his incessant patrolling of Canterbury’s streets he has seemingly joined the psychogeographic club too. In You Are Here, with barely an equation in sight, Watkins succeeds in conjuring up the poetry of mathematics.

noon August 15th 2014’. It is, indeed, a book about time and place. The place is very small and specific: Canterbury in the county of Kent where Watkins currently lives and works. His temporal scope, however, is infinite: he encompasses the dawn of time right through to the (almost) present day. But what happens on 14th August 2014? The answer is small, specific and infinite, not to mention genuinely unsettling. Time is strange, we learn. It does not progress in a strictly linear fashion. Watkins is a mathematician and an exponent of the concept of retrocausality. And in his incessant patrolling of Canterbury’s streets he has seemingly joined the psychogeographic club too. In You Are Here, with barely an equation in sight, Watkins succeeds in conjuring up the poetry of mathematics.