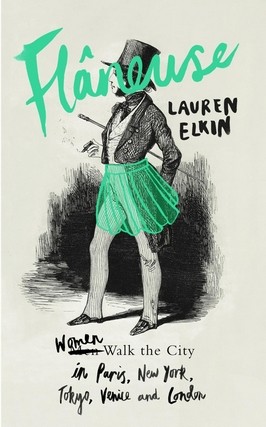

The flâneuse does exist, whenever we have deviated from the paths laid out for us, lighting out for our own territories.

Lauren Elkin is well-qualified to write this book, not only has she lived in Paris, London, New York, Tokyo and Venice, but she has walked the city streets of all of them. If the female manifestation of Baudelaire’s flâneur really does exist, and Elkin contends that she does, then the writer herself is a personification of the idea.

Lauren Elkin is well-qualified to write this book, not only has she lived in Paris, London, New York, Tokyo and Venice, but she has walked the city streets of all of them. If the female manifestation of Baudelaire’s flâneur really does exist, and Elkin contends that she does, then the writer herself is a personification of the idea.

Elkin is an American cultural critic and is currently an academic at the University of Liverpool. Her book is an exhilarating conflation of her personal journey and her wanderings blended with a wider reflection on the female experience of the modern city. In doing so she invokes the works of a host of female writers, including Virginia Woolf, Jean Rhys, Mavis Gallant, Martha Gellhorn and Doris Lessing and, with a refreshingly light touch, she draws on the works of academics such as Griselda Pollock and Homi Bhabha.

Walking is mapping with your feet. It helps you piece a city together, connecting up neighbourhoods that might otherwise have remained discrete entities, different planets bound to each other, sustained yet remote.

Baudelaire’s flâneur, of course, was invariably male. He had leisure time and displayed a somewhat detached attitude, being characterised by his creator as a dandy or dilettante. The flâneur, therefore, was a device that examined the city through exclusively male eyes. Chris Jenks, in his Visual Culture, refers to an ‘imbalance of ocular practice’ in nineteenth-century writing whereby ‘women do not look, they are looked at’. Until the rise of modernism there was little or no literary depiction of urban street-life from a female viewpoint. Until the early twentieth-century and writers like Woolf, Elkin seems to suggest, the flâneuse was invisible and her narrative was silent.

Women have always featured in the street-life of the city, but these were almost exclusively working-class women going about their work and, in a society dominated by wealthy men, their voices went largely unheard. Women were excluded from the literary streetscape of the nineteenth-century city; only those women whose sexuality could be commodified attracted the attention of male writers.

Unwanted attention: American woman in Florence, 1951. Ruth Orkin, Orkin/Engel film and photo archive

Woolf, Dorothy Richardson, Djuna Barnes and other female modernist writers broke new ground by presenting female characters who were free to move through, to gaze at and to explore the streets of the city. The early twentieth-century was a time of rapidly expanding horizons for women, or at least for middle-class women. They moved from the drawing room to the thoroughfares of the city and, soon, fiction began to reflect this development. The change encompassed expanding opportunities in work and leisure activities and included everything from transport, shopping, and fashion to employment, education, and politics.

Elkin takes issue with those commentators who suggest that the word flâneuse is meaningless because flânerie, by its very nature, is an exclusively male occupation, as indeed are all other practices of psychogeography. It’s true that this was the case in the time of Baudelaire and with the leisured wanderers of the arcades of nineteenth-century Paris. But Elkin offers ample evidence to suggest that the flâneuse was alive, well and walking in twentieth-century London, Paris, Tokyo and New York.

A woman strolls past the Trocadero and Eiffel Tower in 1920s Paris, H Armstrong-Roberts Classicstock/Getty Images

Lauren Elkin suggests that flânerie, in its guise of psychogeography, has become something of a male club in recent years. More specifically middle-aged British men, Will Self concedes, each of them to a man Gore-Tex clad and prostate-swollen. But women walkers are still there she argues, citing Laura Oldfield Ford as a contemporary London example. But perhaps it is the case that the flâneuse does not shout about it as loudly as her male counterpart. Women city wanderers, Elkin contends, still feel themselves to be the object of the male gaze and their bodies subjected to sexual commodification:

And it’s the centre of cities where women have been empowered, by plunging into the heart of them, and walking where they’re not meant to. Walking where other people (men) walk without eliciting comment. That is the transgressive act. You don’t need to crunch around in Gore-Tex to be subversive, if you’re a woman. Just walk out your front door.