Washington Irving was an American writer who spent much of his early literary career living in England. But I only discovered recently, while doing some research for a piece on the Old Dee Bridge, that he was also a frequent visitor to Chester. When he first visited the city in 1825 he would have travelled from London by coach; an uncomfortable journey lasting several days. At least he was able to find some comfort in the inns he stayed at along the way:

…that picture of convenience, neatness and broad honest enjoyment, the kitchen of an English inn.

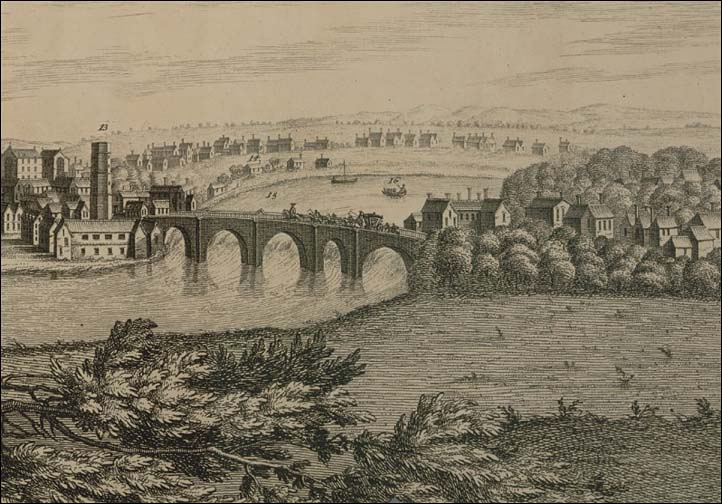

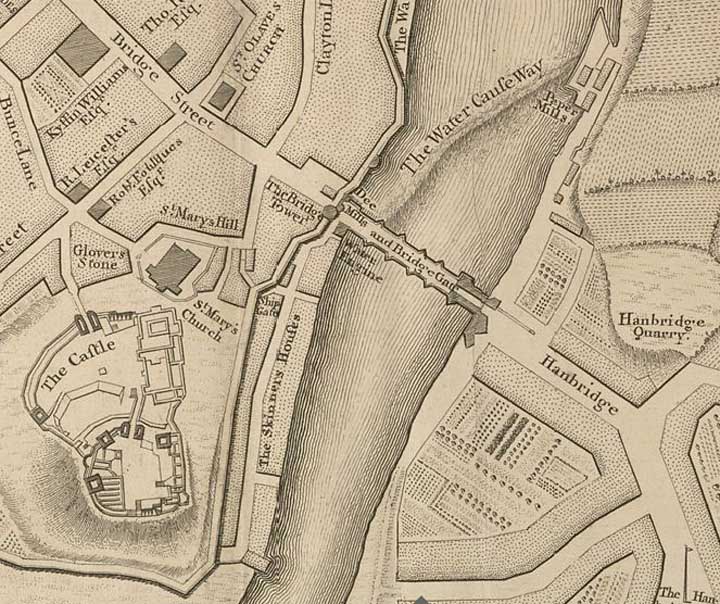

Irving was impressed by Chester and loved to explore its Roman ruins and medieval streets. As a student of European folklore, he also found much to pique his interest. Taking a stroll one day from the centre of Chester across the sandstone arches of the Old Dee Bridge he came across a maypole on the Handbridge side of the river:

I shall never forget the delight I felt on first seeing a May-pole. It was on the banks of the Dee, close by the picturesque old bridge that stretches across the river from the quaint little city of Chester. I had already been carried back into former days by the antiquities of that venerable place… the May-pole on the margin of that poetic stream completed the illusion. My fancy adorned it with wreaths of flowers and peopled the green bank with all the dancing revelry of May-day. The mere sight of this May-pole gave a glow to my feelings and spread a charm over the country for the rest of the day.

Sadly, the maypole, although once a fixture at the Handbridge end of the bridge for many years, is now long gone.

Irving’s interest in folklore and the uncanny manifested itself in many of his short stories; Rip Van Winkle and The Legend of Sleepy Hollow being amongst the best known.

The Legend of Sleepy Hollow is set in 1790 in a secluded valley called Sleepy Hollow in a predominantly Dutch area of upstate New York. The area is alive with tales of ghosts and hauntings, the most terrifying of which is the legend of the Headless Horseman. The horseman, as explained by locals to Ichabod Crane, a newly-arrived schoolmaster from Connecticut, was a soldier who lost his head in battle to a stray cannon-ball. On dark nights he rides through the valley still, they insist, with his head tucked under his arm.

One night, riding home from the farm of Katrina Van Tassel, the young woman he intends to marry, Crane is chased by the Headless Horseman and, in fear for his life, flees Sleepy Hollow never to be seen in the area again. The reader is left to ponder whether Crane’s pursuer was really a terrifying spectre, or merely a love-rival in disguise.

Irving’s tale has endured and, indeed, it has been filmed on several occasions, the most recent being Tim Burton’s adaptation in 1999. But he did not invent the idea of the headless horseman; folk tales of headless earth-bound spirits on horseback abound throughout Europe. In England Cheshire seems to be particularly cursed by such legends. No doubt Irving, with his active interest in folklore, would have encountered many of these tales during his visits to Chester.

Wybunbury, some twenty-seven south of Chester, has long been home to a widespread headless horseman myth. He is said to ride across Wybunbury Moss, a boggy area just outside the village. The Moss is also home to one of the North of England’s many Ginny Greenteeth legends: the green-skinned, sharp-toothed hag who emerges from ponds and pools and pulls the unwary in to their doom. Another headless horseman, allegedly the ghost of a slain Royalist from the English Civil War, is said to ride out on a lonely lane near Halton, to the north of Chester.

However, Irving’s interest in headless spirit mythology seems to have been ignited by one particular encounter that occurred when he was travelling by coach from Birmingham to Chester. The coach stopped at a village called Duddon, eight miles or so east of Chester. Irving was intrigued as to why the village inn was called The Headless Woman. The landlord explained to him that it was named after a woman called Grace Trigg, a servant to a local Royalist family, who was beheaded in the attic of the inn by rampaging Parliamentary troops. She regularly haunts the inn, the landlord warned, and seeing her was a sign of impending disaster for the person concerned.

Against the landlord’s advice, Irving insisted on staying the night at the inn and had a bed made up in the attic room. He kept a vigil all night, but did not see the headless woman. He did, however, claim to have heard a woman sobbing in the night and, in the morning, found a patch of blood on the floor of the attic.

Prompted by his experience in Cheshire, Irving spent several months researching headless ghost tales. He found that that their incidence was ubiquitous throughout the British Isles. Many of the legends involved headless horsemen, tales of which have persisted right through until the present day. Irving would be amused, no doubt, to learn that his fictional The Legend of Sleepy Hollow is still the best-known of these stories.

Pingback: The Last Drop & The Bucket of Blood: The Folklore of Odd Pub Names