Not so long ago The Guardian called Wrexham ‘a veritable Paris of what is lost’. For, despite the city’s rich history as a market town and the UNESCO World Heritage Site status of its Pontcysyllte aqueduct, Wrexham is most notable for the significant buildings it has destroyed. But it is not unique in this regard: the post-war city planners of Glasgow, Newcastle-upon-Tyne, Birmingham and many other towns and cities continued the destruction of British urban heritage started by the Luftwaffe.

This is not a simple ‘old buildings are good and modern ones are bad’ knee-jerk reaction. Indeed, one of the saddest losses from Wrexham’s skyline in recent years was the demolition in 2020 of the brutalist concrete masterpiece that was formerly the city’s police headquarters.

In a similar fashion, a slew of other buildings have been reduced to rubble in recent decades. When the Hightown flats were built in the 1960s they were praised for their innovative design concept. The concrete components of the 191 flats were factory-built and assembled on site creating light, airy homes each forming part of a small, neighbourly cluster. Lack of investment in the 1980s and 1990s, however, caused the fabric of the flats to steadily deteriorate and they were demolished in 2011.

In a similar fashion, a slew of other buildings have been reduced to rubble in recent decades. When the Hightown flats were built in the 1960s they were praised for their innovative design concept. The concrete components of the 191 flats were factory-built and assembled on site creating light, airy homes each forming part of a small, neighbourly cluster. Lack of investment in the 1980s and 1990s, however, caused the fabric of the flats to steadily deteriorate and they were demolished in 2011.

From a much earlier era, several of the Wrexham area’s large country houses have met a similar fate. Acton Hall was formerly the home of the Jeffreys family including the notorious ‘hanging judge’, George Jeffreys. The most recent iteration of the house was built in 1786 and passed through various hands, including the US military in World War Two, until it fell into disrepair and was demolished in 1955.

From a much earlier era, several of the Wrexham area’s large country houses have met a similar fate. Acton Hall was formerly the home of the Jeffreys family including the notorious ‘hanging judge’, George Jeffreys. The most recent iteration of the house was built in 1786 and passed through various hands, including the US military in World War Two, until it fell into disrepair and was demolished in 1955.

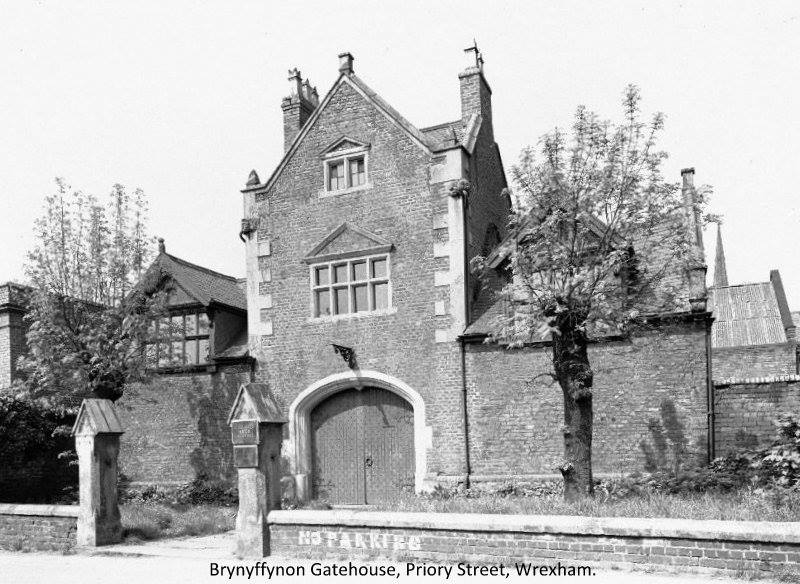

Nothing remains of the house, but part of the estate became a public park and the rest was sold off for housing. An even older building, the Priory Gatehouse from the late sixteenth-century was demolished in 1966.

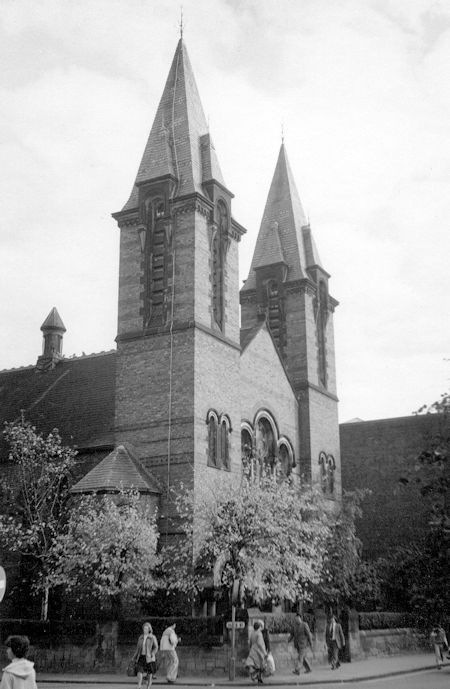

Seion Welsh Presbyterian Chapel in Regent Street was built in 1867 in the Romanesque style and its twin spires were a prominent feature of Wrexham’s skyline for over a 100 years. With a capacity for over 800 worshippers, Seion catered for a large proportion of the town’s Welsh-speaking non-conformist community. Structural problems were identified in the 1970s and the building was demolished in 1979.

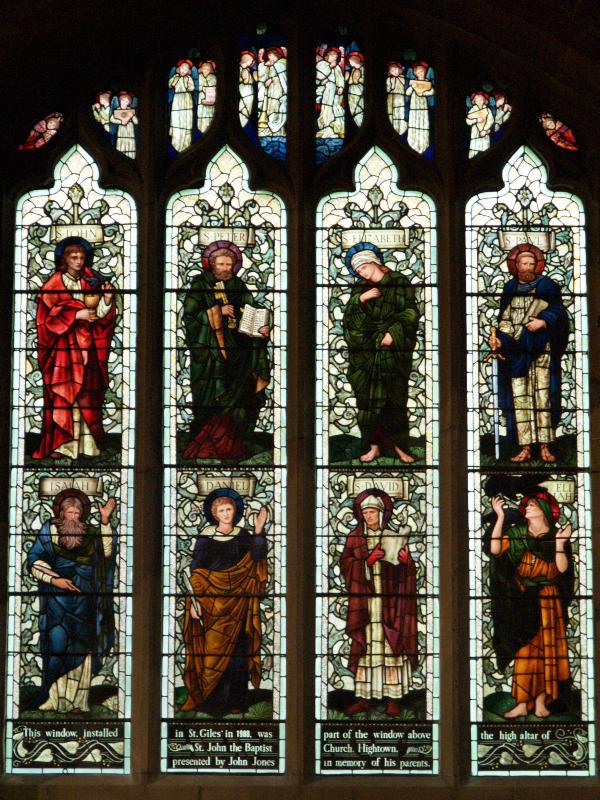

Ten years later another of Wrexham’s churches, St John the Baptist in Hightown, was razed to the ground.

Built in 1908, St John’s was notable for its stained glass window designed by the prominent Pre-Rapaelite artist, Burne-Jones. Fortunately, the window was removed prior to the demolition of the church and now has a new home in St Giles parish church in the town centre.

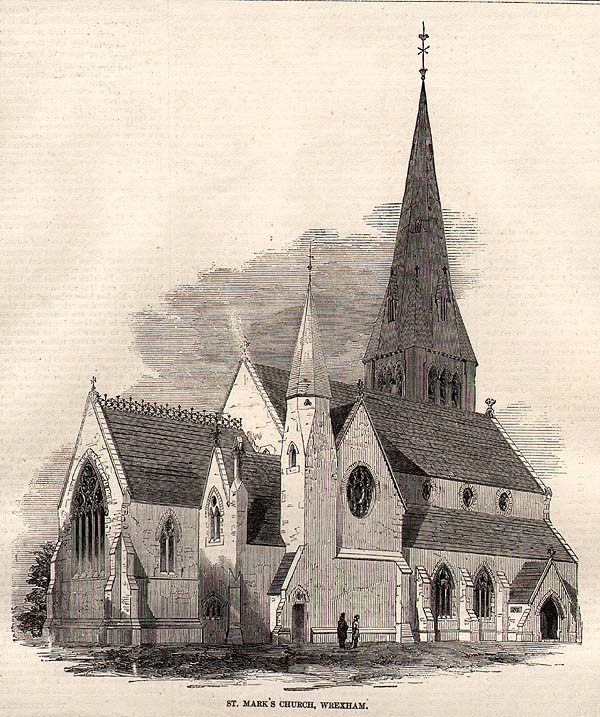

St Mark’s Church, a building of arichitectural-note built in 1862, was visited by the wrecking ball in 1959.

The Opera House in Henblas Street was built in 1909 . It seated an audience of 800 and was regularly used for concerts and plays. In 1929 it was converted into a cinema known as the Hippodrome.

In 1988 it was split into two screens to try to keep up with multiplex trend but, by 1997, it finally closed its doors as it could not compete with the major cinema chains. The site is now a vacant lot with plans to make it into a town centre park.

Historically, Wrexham grew up and expanded as a market town. It served a rich agricultural hinterland and was situated on a major trade route on the Welsh/English border. Several of the old market halls from the Victorian era and before remain, but others are no more. The Beast Market, where livestock was traded, has gone, as has Manchester Hall, Birmingham Square and Yorkshire Square,well-known for linen, hardware and woolen goods repectively.

The Vegetable Market, an indoor market hall built in 1898 with a mock-Tudor frontage was demolished in the 1980s to make way for a shopping centre.

The Vegetable Market, an indoor market hall built in 1898 with a mock-Tudor frontage was demolished in the 1980s to make way for a shopping centre.

Further information about all of these buildings, and many others, can be found in W. Alister Williams’ excellent The Encyclopaedia of Wrexham.

I didn’t know any of this! Fascinating – thank you

Thanks Liz 😊

Oh no, that amazing brutalist police building – devastating!