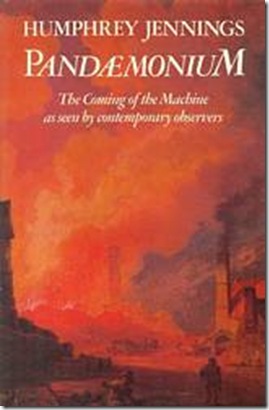

I first read Pandaemonium shortly after it was published in 1985 and have enjoyed dipping into it from time to time ever since. I have the Andre Deutsch version, the one with the cover featuring P.J. de Loutherbourg’s ‘Coalbrookdale at Night’; a picture which gives me a frisson of sulphur-charged excitement whenever I look at it.

Humphrey Jennings was a British documentary film-maker whose career was cut tragically short in 1950 when, at the age of just forty-three, he fell from a cliff in Greece when scouting film locations. Jennings was a socialist, a champion of surrealism and one of the founders of Mass Observation. He was also a pioneer of neo-realism, coaxing extraordinary performances from non-professional actors in several of his works. His best known films are Fires Were Started, The Silent Village and A Diary for Timothy. Lindsay Anderson described Jennings as ‘the only real poet that British cinema has produced’.

Jennings first started the Pandaemonium project in 1938, initially as a series of talks for miners in South Wales when filming The Silent Village. But the anthology was not completed until nearly forty years after his death, in a collaboration between his daughter, Mary-Lou Jennings, and his former Mass Observation colleague, Charles Madge.

Pandaemonium is a history of Britain’s Industrial Revolution told through the words of those who witnessed it; ordinary men and women, industrialists, politicians and artists. Jennings’s collection is eclectic: books, articles, diaries and letters spanning a period of more than two hundred years. Many of the extracts featured are written by names with whom we are still familiar: Shelley, Carlyle and Charles Kingsley, for instance. Others who are quoted, the people of no property, would otherwise be long forgotten.

Jennings’s vision was a filmic one. Indeed, he refers to the extracts he compiled as ‘images’. But this is not just reportage, Jennings aimed to create a work that was of the imagination; a word film which captures the full range of human responses to a period of cataclysmic change in British society.

The book’s title is taken from Book 1 of Milton’s Paradise Lost, The Building of Pandaemonium. The noise, the smell and the heat of coal, iron and engines pervade this book. A nation, a society and a people turned upside down. The coming of The Machine.

Many of those whose words are featured in Pandaemonium lament for something they see being lost in the furnace of industrialisation:

A frightful scene ….. a dense cloud of pestilential smoke hangs over it forever ……. and at night the whole region burns like a volcano spitting fire from a thousand tubes of brick. But oh the wretched thousands of mortals who grind out their destiny there!

Thomas Carlyle, 1824

Others bemoan the foul streets and smoking factories which spring up where once there were trees and fields:

Pimlico and Knightsbridge are now almost joined to Chelsea and Kensington; and if this infatuation continues for half a century, I suppose the whole county of Middlesex will be covered with brick.

The Expedition of Humphrey Clinker, Tobias Smollett, 1771.

At least as many, however, discern hope for the future amongst all the trials of the present:

There is a time coming when realities shall go beyond any dreams that have been told of these things. Nation exchanging with nation their products freely… universal enfranchisement, railways, electric telegraphs, public schools… the greatest of the moral levers for elevating mankind.

The Autobiography of a Working Man, Alexander Somerville, 1848

This duality, the need to pass through fire to forge a new Jerusalem, is perhaps what Frank Cottrell Boyce had in mind when he scripted the Olympic opening ceremony. In Milton’s vision of Pandaemonium the power of iron and fire is wrested from the Devil to be used by mankind. Boyce and Jennings are seemingly joined in a Promethean bond. Indeed, Boyce gives specific credit to the influence of Jennings’s book on the ideas and imagery he brought to the 2012 project.

Jennings’s approach to the texts that he selects betrays his leaning towards Marxism and Romanticism. But, above all else, this is the vision of film-maker, a man who loved to frame images and paint pictures, in this case with words. So how does one set about reading such a labyrinthine set of texts? Humphrey Jennings foresaw this issue and advised:

There are at least three different ways in which you may tackle this book. First, you may read it straight through from the beginning as a continuous narrative or film on the Industrial Revolution. Second, you may open it where you will, choose one or a group of passages and study in them details of events, persons and thoughts as one studies the material and architecture of a poem. Third way, you begin with the index – look up a subject or idea, and follow references, skipping over gaps of years to pursue its development.

Jennings never lived to construct this index, but we have Charles Madge to thank for doing so posthumously from his friend’s notes. Madge’s ‘theme sequence’ provides the key to help unlock the treasures within Jennings’s work.

London 2012 image courtesy of the Daily Telegraph