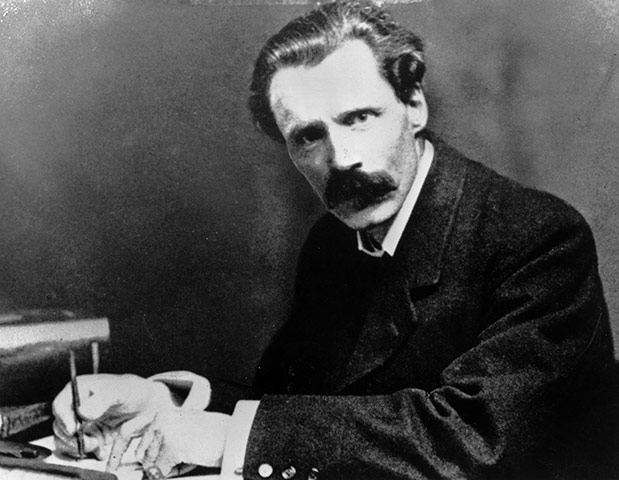

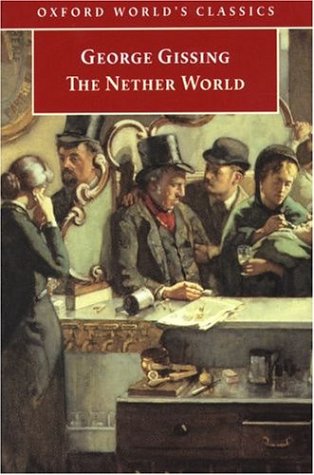

George Gissing is, in many ways, a forgotten author. His subject matter was unrelentingly grim, his world view invariably pessimistic and his work lacked any hint of literary experimentation. Perhaps, then, he deserves to be forgotten. But that would be to overlook his achievements as one of the most resonant voices of the neglected margins of late Victorian society and, above all, as one of the first great London writers.

Gissing was born in Wakefield in 1857 to middle-class parents. A brilliant scholar, he attended university but was sent down after stealing from fellow students to fund his affair with a prostitute with whom he had fallen in love. Gissing spent much of his working life in penury in the Clerkenwell and Islington areas of London. But a late blossoming of his career brought him literary acceptance and some degree of financial security in his final years. George Gissing died in France at the age of 46.

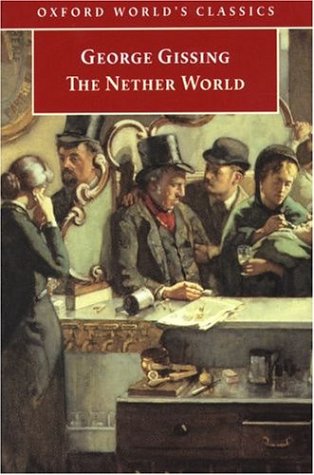

The Nether World (TNW) was written in the late 1880s, and yet its themes are startlingly contemporary, being a novel about London’s simmering underclass. Gissing writes about London. In contrast to the pervading confidence of his era, he characterises London, not as the vibrant hub of a great empire, but as a place of loneliness, alienation and spiritual despair:

Opposite, the shapes of poverty-eaten houses and grimy workshops stood huddling in the obscurity. From near at hand came shrill voices of children chasing each other about – children playing at midnight between slum and gaol! (TNW)

The Nether World presents us with a panorama of working class life in Clerkenwell. The central characters are Sidney Kirkwood, an embittered but sensitive young craftsman, and Jane Snowdon, who has spent her childhood as a bullied and unpaid domestic help in the household of the Peckover family. As in his other great novel, New Grub Street, Gissing uses an elderly man’s will as his plot device. The will in this case is that of Michael Snowdon, Jane’s grandfather, who returns from Australia intent on using his wealth for the betterment of London’s poor. He wishes Jane to be the instrument of this bequest, but Jane feels weighed down by the enormity of her grandfather’s plan. In the end she loses both the money and her soul mate, Sidney.

Other characters in the book fare no better; they seem ensnared by the power of The Nether World. Joseph Snowdon, Jane’s father who abandoned her when she was an infant, ingratiates himself with Jane’s grandfather and is rewarded when Michael’s will is changed to favour him. But he loses his money in a speculative venture in America and dies penniless, a broken man. Clem Peckover marries Joseph, despite feeling nothing but contempt for him, in an ill-conceived attempt to get at Michael’s Snowdon’s legacy. Sidney marries Clara out of a sense of duty and takes on the burden of caring for John Hewett’s children. Bob Hewett is struck by a cart when running from the police and dies. Mrs Candy drinks herself to death. Jane and Sidney resign themselves to a life of poverty and thwarted hopes without even the comfort of each other. All Michael Snowdon’s plans end in failure; nothing changes. His money is lost and his hopes for Jane evaporate:

She, no saviour of society by the force of a superb example; no daughter of the people, holding wealth in trust for the people’s needs. (TNW).

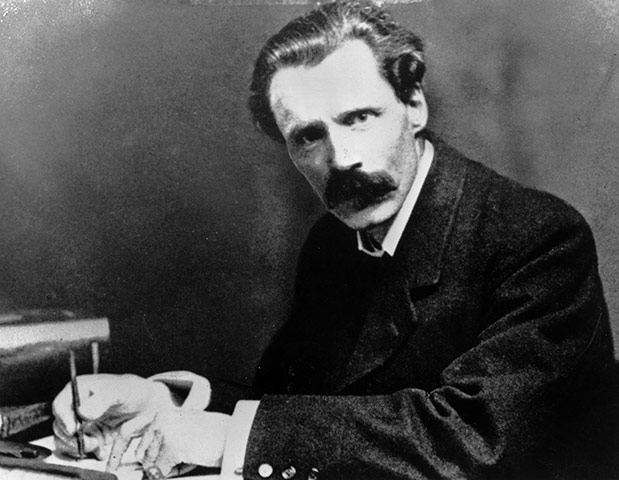

George Gissing

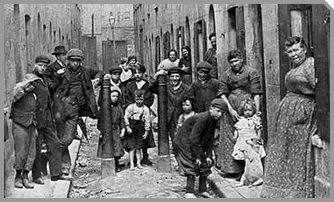

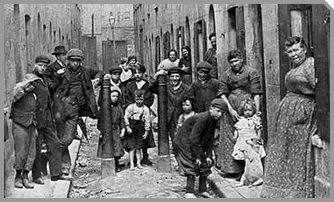

At the time that Gissing wrote The Nether World, the population of Britain’s cities, in particular London, was rapidly increasing, with many of the new inhabitants having moved to the city in an attempt to escape rural poverty. The divide between rich and poor was expanding and there was a rise in political radicalism. Dickens had written about such urban poverty in a previous generation but, unlike Gissing, he brought a sense of optimism and sentimentality to his subject. In Gissing’s time, James Thomson explored the writer’s experience of the city in The City of Dreadful Night, in which he represented the city as a place of death and destruction. But, whilst Thomson’s poem is a Dante-influenced circular journey through the dreamscape of a city at night, Gissing relies on detailed realism to convey the power of his vision of London.

The Nether World immerses the reader into the urban poverty of that time. Very few characters of higher social classes are featured; the upper world is distant, anonymous, rarely glimpsed. Sidney Kirkwood makes jewellery, to be bought by people with the money to do so, but their presence is a mere abstraction. The Nether World also shows Gissing’s pessimism about the ability of the poor to overcome their circumstances. Indeed, he bemoans their lack of ambition. Writing of a bank holiday outing to the Crystal Palace, Gissing despairs over the coarseness and vulgarity of his characters:

See how worn-out the poor girls are becoming, how they gape, what listless eyes most of them have! The stoop in the shoulders so universal among them merely means over-toil in the workroom. Not one in a thousand shows the elements of taste in dress; vulgarity and worse glares in all but every costume….. Mark the men in their turn: four in every six have visages so deformed by ill-health that they excite disgust; their hair is cut down to within half an inch of the scalp; their legs are twisted out of shape by evil conditions of life from birth upwards. (TNW).

Indeed it is, in Gissing’s eyes, this very acceptance of a debased way of living, a willingness to embrace degradation on the part of most of his working class characters, that causes him such anguish.

A mood of pessimism hangs over the London of Gissing’s novels. In The Nether World he sees no way out of the cycle of poverty. Underlying his work is the writer’s experience of the city. For Gissing, who learned about hardship at first hand and experienced artistic disappointment during his time in London, the city represents nothing but ugliness and despair. Casting a narrative eye over the Farringdon Road Buildings in The Nether World, he comments:

Pass by in the night, and strain imagination to picture the weltering mass of human weariness, of bestiality, of unmerited dolour, of hopeless hope, of crushed surrender, tumbled together within those forbidding walls. (TNW)

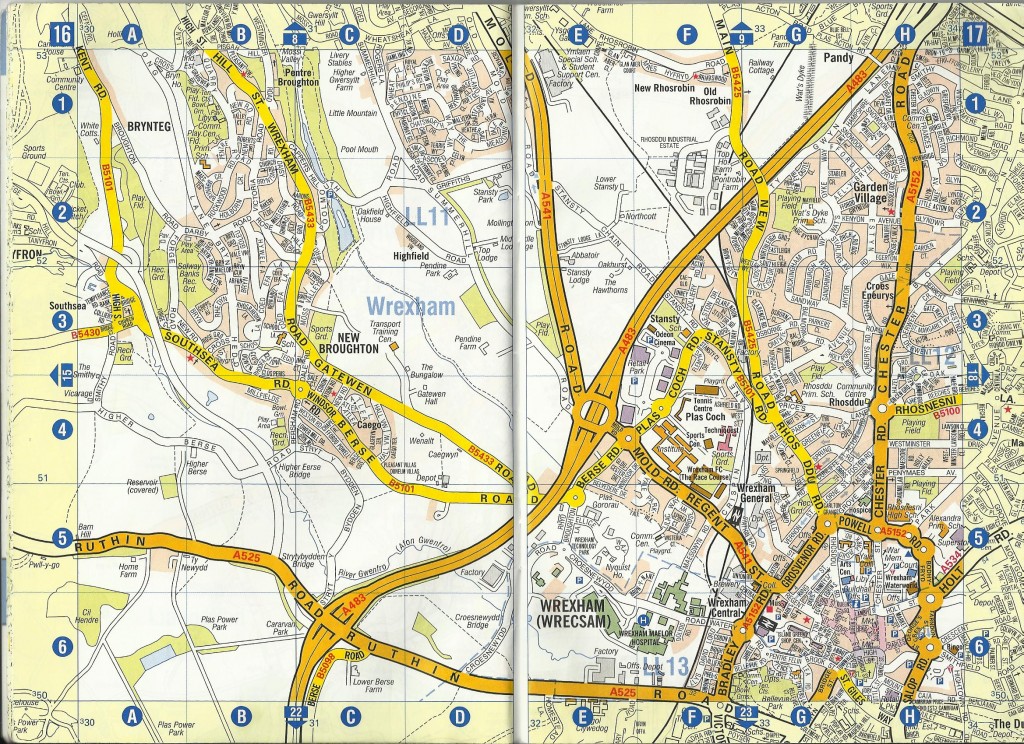

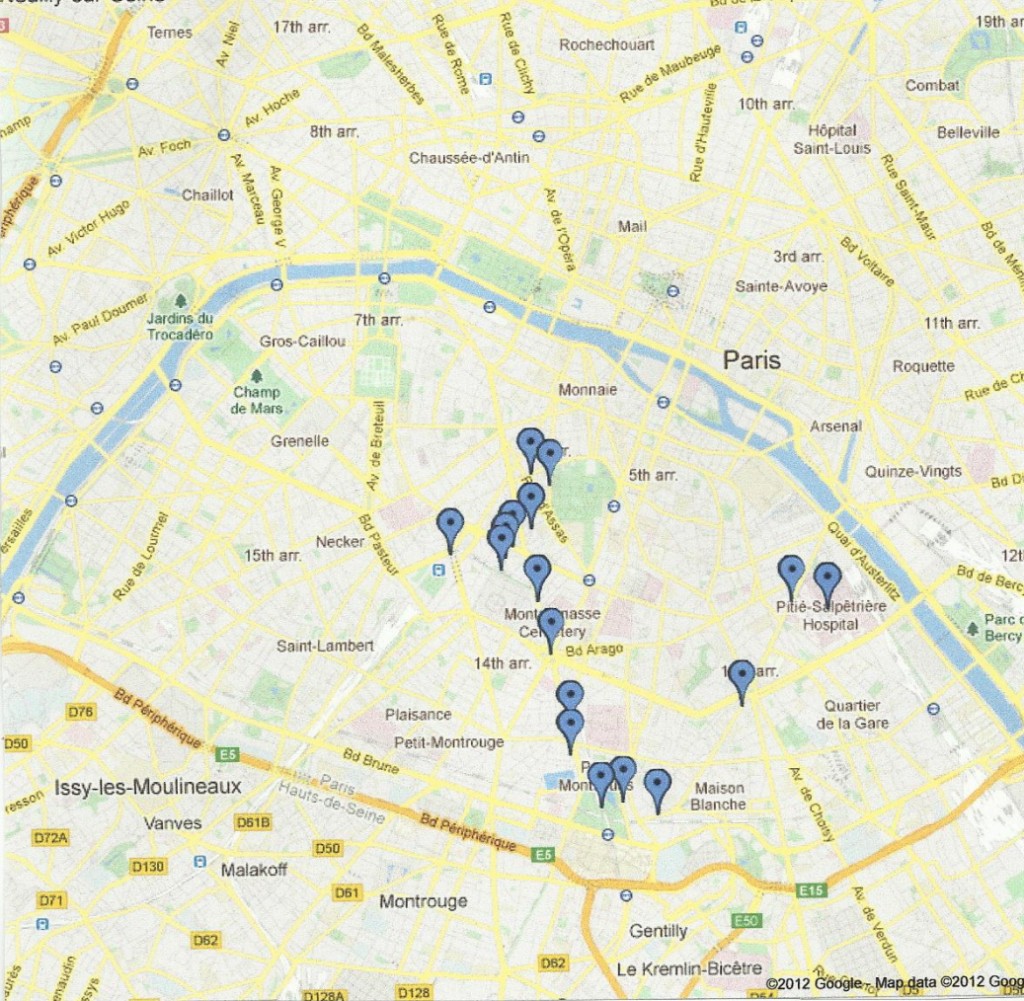

One key point in the novel is that the London street names used are ‘real’ streets in the areas featured and their names would be familiar to many of Gissing’s readers at the time of publication. Indeed, many of these streets still exist.

Of particular interest to contemporary psychogeographers, is the fact that The Nether World offers numerous examples of the plot being moved forward by a character walking the city streets. John Hewett, for instance, in the hope of finding his daughter Clara, obsessively ‘walked about the streets of Islington, Highbury, Hoxton, Clerkenwell’. (TNW).

Public transport is only used on special occasions. It is a public holiday and the occasion of their marriage that brings Bob and Pennyloaf Hewett to join the throngs on the train to visit the Crystal Palace. Most of the action takes place within a mile or two of Clerkenwell Green. When characters move about, invariably on foot, the streets they pass along are systematically named, as if to lay down the markers of the territory to which they are bound. Even Sidney and Clara’s holiday in Essex is a mere interlude before returning to London, the ‘city of the damned’ (TNW), and the confines of their life in Clerkenwell.

- Clerkenwell Green

When we read an earlier great writer of London, William Blake, we discover a city that offers transcendent, spiritual possibilities. But, for Gissing, the city represents only loneliness and alienation. Bob Hewett, in The Nether World, sees crime as a way out, but dies from injuries he receives when fleeing from the police. Clara’s attempt at a career in the theatre ends in physical disfigurement and self-loathing. Mrs Candy makes a kind of escape, but only into the oblivion of the bottle:

Rage for drink was with her reaching the final mania. Useless to bestow anything upon her; straightway it or its value passed over the counter of the beershop in Rosoman Street. She cared only for beer, the brave, thick, medicated draught, that was so cheap and frenzied her so speedily. (TNW).

The city empowers some: Clem Peckover, with her animalistic energy, is, in Darwinian terms, very much fitted to her environment. However, Gissing’s London ensnares others. The Nether World opens outside a prison and ends in a graveyard, as if to emphasise that, from start to finish, life offers one no escape from one’s fate.

Victorian social investigators often suggested that London was divided into a prosperous West End and a downtrodden East End. For Gissing the divide was much more complex, with overlapping divisions on a psychological, sexual and social basis. Indeed, some commentators refer to Gissing’s ‘zoning’ of London. The Nether World is an exploration of these divisions.

In The Nether World, Gissing portrays a working class prolific in its reproductive capacity; growing and spreading outwards from the centre of the city:

Look at a map of greater London, a map on which the town proper shows as a dark, irregularly rounded patch against the whiteness of suburban districts, and just on the northern limit of the vast network of streets you will distinguish the name of Crouch End. Another decade, and the dark patch will have spread greatly further; for the present, Crouch End is still able to remind one that it was in the country a very short time ago. (TNW)

Hurrying to work, thronging through the streets of Clerkenwell; the unconscious, undirected power of Gissing’s mass is embodied in its very numbers. This under class, many conservative writers of that time suggested, was not just feckless and debased, but a real threat to the rest of society by the seemingly exponential growth in its numbers.

Gissing’s research for The Nether World was meticulous. He filled several notebooks with his observations of how people in Clerkenwell lived and worked. Then, in the finished novel, he concentrated on the small details but, in doing so, he gave clues as to social change and provided cultural resonance. Be it the Hewett’s lodgings in the Peckover house or Mrs Candy’s sordid room in Shooter’s Gardens, the details are described with clinical precision:

The room contained no article of furniture. In one corner lay some rags, and on the mantel-piece stood a tin teapot, two cups, and a plate. There was no fire, but a few pieces of wood lay near the hearth, and at the bottom of the open cupboard remained a very small supply of coals. A candle made fast in the neck of a bottle was the source of light.(TNW).

Shooter’s Gardens represents the bottom-most pit of Clerkenwell’s slums and features in several of the most harrowing scenes in The Nether World. It is a backdrop to death and despair:

The slum was like any other slum; filth, rottenness, evil odours, possessed these dens of superfluous mankind and made them gruesome to the peering imagination. (TNW).

As Adrian Poole puts it, ‘the hell within a hell at the heart of the nether world is a slum called Shooter’s Gardens’ (Adrian Poole, Gissing in Context (London, Macmillan, 1975) p. 92). And Mad Jack, a homeless character, is the demented chronicler of this hell.

This life you are leading is that of the damned; this place to which you are confined is Hell! …. This is Hell – Hell – Hell! (TNW).

But Gissing is less concerned with the causes of poverty than with its human face. He drives home the every day indignities resulting from lack of money. Gissing is consistent in his pessimism. Just as there is no escape for all but the most exceptional individual, so there seems to be no answer to the grinding poverty afflicting huge areas of London. Gissing rejects both political radicalism and religion as impractical and doomed to failure and he mocks the efforts of those who offer charity. Miss Lant, a ‘charitable lady’ in The Nether World, is described in unflattering terms:

Unfortunately the earlier years of her life had been joyless, and in the energy which she brought to this self-denying enterprise there was just a touch of excess, common enough in those who have been defrauded of their natural satisfactions and find a resource in altruism. She was no pietist, but there is nowadays coming into existence a class of persons who substitute for the old religious acerbity a narrow and oppressive zeal for good works of purely human sanction, and to this order Miss Lant might be said to belong. (TNW).

Whilst highlighting the plight of the urban poor, Gissing also expresses his distaste for their degradation and his frustration with their lack of imagination in conceiving of a better way of living:

Well, as every one must needs have his panacea for the ills of society, let me inform you of mine. To humanise the multitude two things are necessary – two things of the simplest kind conceivable. In the first place, you must effect an entire change of economic conditions: a preliminary step of which every tyro will recognise the easiness; then you must bring to bear on the new order of things the constant influence of music. (TNW).

Gissing’s city is oppressive and monotonously utilitarian:

Acres of these edifices, the tinge of grime declaring the relative dates of their erection; millions of tons of brute brick and mortar, crushing the spirit as you gaze. (TNW).

A train journey through the ‘pest-stricken regions of East London’ reveals the:

streets swarming with a nameless populace, cruelly exposed by the unwonted light of heaven; stopping at stations which it crushes the heart to think should be the destination of any mortal. (TNW).

The effect Gissing creates, so it seems to the reader, is that the very streets and houses stifle one’s soul. Only the exceptional individual can break free. But more often than not he will go under, as does John Hewett, or prosper but deteriorate morally, such does Clem Peckover.

Again and again in The Nether World Gissing suggests that the city is a place of loneliness and isolation. Indeed, an isolated person sitting in his or her lonely room at night is an iconic image in both these works and can be viewed as a metaphor for the alienating experience of the city as a whole. For Clara, brought home by her father, physically and mentally scarred from her time in the theatre, her little room in the Hewett’s lodgings becomes ‘her cell throughout the day’. (TNW).

Gissing, I would argue, changed the way we view cities. In setting The Nether World and New Grub Street, two of his most important novels, in London he emphasised the unique importance of that city. But Gissing neither proselytised for social change nor did he hark back to some notional rural idyll. Instead he presented the city, and all the grimy details of life as it affected the ‘mass’ and the individual, in realistic detail. As John Spiers puts it:

Just as JMW Turner changed the way we look at skies and their ‘reality’ and John Ruskin how we view Venice, Gissing is one of those who has shaped how we see and experience ‘the city’. (John Spiers (Ed), Gissing and the City (London, Palgrave Macmillan, 2005) p. 8).

References

George Gissing, The Nether World (Oxford, Oxford University Press, 1992)

Paul Delany, George Gissing: A Life (London, Weidenfeld & Nicholson, 2008)

Nicholas Freeman, Conceiving the City: London, Literature, and Art 1870-1914 (Oxford, Oxford University Press, 2007)

Albert Fried and Richard M Elman (eds), Charles Booth’s London: A Portrait of the Poor at the Turn of the Century, Drawn from His ‘Life and Labour of the People of London’ (London, Hutchinson, 1969)

John Goode, George Gissing: Ideology and Fiction (London, Vision Press, 1978)

Jacob Korg, George Gissing: A Critical Biography (Brighton, Harvester Press, 1980)

Sally Ledger and Roger Luckhurst (Eds), The Fin de Siecle: A Reader in Cultural History c.1880 – 1920 (Oxford, Oxford University Press, 2000)Adrian Poole, Gissing in Context (London, Macmillan, 1975)

Adrian Poole, Gissing in Context (London, Macmillan, 1975)

John Spiers (Ed), Gissing and the City (London, Palgrave Macmillan, 2005)

James Thomson, The City of Dreadful Night (Edinburgh, Canongate Classics, 2000)

Like this:

Like Loading...

![FieldsBeneathFront[1]](https://psychogeographicreview.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/03/FieldsBeneathFront11-191x300.jpg)