A guest post by Fernando Sdrigotti

Clerkenwell: a hectic hub in the centre of London. Today, as always, several times co-exist here. Today, the times of the media industry, the postal workers, the Italian Diaspora, and a (mostly white) working-class. I lived in Clerkenwell from late 2009 to late 2011; I was fascinated then; and I am fascinated now (I write these words under the same spell). I used to spend my mornings pushing a pram around the area; my daughter, now two, was an early drifter. Now this is arguably not the best place to push a pram; yet I hold dearly these times where we could dérivé around Clerkenwell, just the two of us, alone in the crowd of early morning workers and local drunks.

We would reproduce the same journey on a daily basis. The starting point would always be Mount Pleasant Sorting Office, around the corner from our flat.

Across the road from Mount Pleasant sorting office

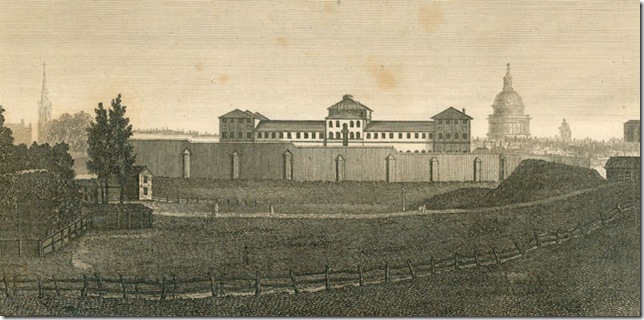

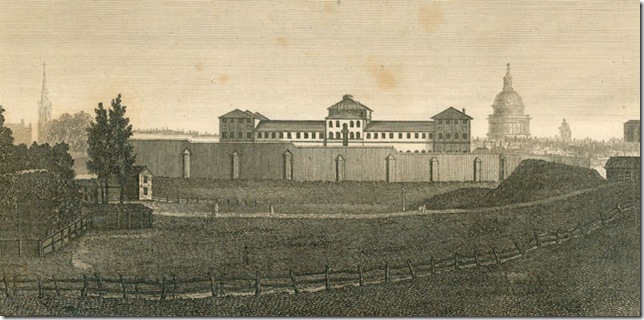

This space, currently housing one of the largest sorting offices in Europe, used to be known as Coldbath Fields Prison (1794 – 1885). Something of its past survives in the building. An imaginary palimpsest, perhaps; but there is something carceral about the place.

The sorting office as seen from Farringdon Road

Etching of Coldbath Field Prison (Source: The British Postal Museum & Archive)

The sorting office is a spiky, brutal, affair. The windows don’t let one see more than bits of postal clutter and the occasional postman (before the current redevelopment; the building is now covered in scaffolding and Christo-like fabric; I dread to think what will become of it once the redevelopment of the area is finished). I’ve always fantasised about asking to be led into the building; I understand this is possible; I don’t know why I never did it (perhaps the fear of ruining an ideal relationship with this building?).

Back of the building, intersection of Warner Street and Phoenix Place.

Towards the back there’s a huge parking lot frequently packed with red vans. And, although invisible to the eye, there are tunnels underneath the ground, tracing wanton trajectories across the city, connecting who knows which buildings with who knows which other underground spaces. In the past Royal Mail used to run their own underground train, carrying only letters. Letters being the most anthropologically charged of objects, the trajectories remain for whoever wants to feel them. You might imagine them being love letters; I prefer to imagine them as utility bills and junk mail, the kinds of epistolarity the city imposes on its citizens.

I have used this space in my fiction writing. Two of the stories of my upcoming book (Ordinary Stories in Minor English) take it as setting or background. In the first one, a group of black and Asian postal workers manage to prevent a plot to kill the Queen with a pair of exploding shoes sent to her by Mossad; on the second one a young barmaid who works in the pub across the road can’t sleep due to the vibrations (the charged letters) she perceives from the sorting office (her cocaine habit might contribute to her insomnia but she blames the sorting office nevertheless). The sorting office also has a secondary role in many other short stories I wrote around this time. I guess it was my way of taking something of this building with me when I left the area.

After Mount Pleasant it would be Spa Fields, just a couple of hundred metres east down Farringdon Road. Now home to mostly local winos, media clerks on lunch-break, and the staff of the London Metropolitan Archive, Spa Fields was a burial ground from 1777- 1849.

Back gate; Spa Fields

The crematorium used to occupy the space in which the park attendant’s house lies today. The burial ground was originally planned for +2700 interments. According to British History Online by “in fifty years it was carefully computed that 80,000 interments had taken place in this pestilential graveyard”. This practice was permitted by the constant exhumation, chopping-up, and cremation of older corpses. Due to the infectious smells that emanated from the place, all the corpses were finally removed and relocated to other cemeteries at the then outskirts of the city. This practice continues today in the expulsion – via extortionate rent – of the original inhabitants of the area. Gentrification is always a gory business. One might thing Clerkenwell is already fully gentrified; one should think carefully. There’s always the potential for further expulsions. The local council flats are today a mixed affair: working families cohabit with students, media people and City yuppies. There is nothing stopping the huge monster that is the City of London from conquering what it hasn’t already conquered. The soaring rents in the area, in addition to the housing benefit cap should do their part in contributing to this.

Formerly a crematorium and bone-house, now the park attendant’s house.

I used to spend several hours every morning walking in circles in this square. Babies are pram-fascists that only sleep while on moving wheels. Nevertheless I owe these lost hours the pleasure of re-reading W. G. Sebald’s The Rings of Saturn. I guess the only way this book can get any better is if one reads it while walking.

Sooner or later the young fascist child would wake up. We would then head to Saint James Clerkenwell church, just a hundred metres north from Clerkenwell Green, temporary home to Vladimir Lenin. The legend states that Lenin met Stalin at a pub just around the corner from this church. I ignore whether they walked on the churchyard; but I guess they did: atheists cannot resist religion’s call.

You don’t see any commies around here now. This is also mainly a place for media people on their lunch break and local drunks. The latter are a fixture in Clerkenwell. The area is close enough to Central London and far enough from Westminster’s and the Met’s Street Homelessness Unit. I used to talk to one of them, a guy with a northern accent. He had just been released from prison after many years; he shot a man but he failed to kill him; the man had abused him when the homeless guy was a child; he waited almost ten years and he took his revenge; he regretted not having killed him; he didn’t regret having spent time in jail. I used to hear all this from behind a pushchair; and so did my daughter (luckily she didn’t understand English back then).

Saint James Church, Clerkenwell

Now I am guilty of living in another gentrified area of London (is there any area that isn’t gentrified here?). But there are no industrial buildings over here; no prisons but the everyday; the postmen only turn up to deliver letters (bills); and you don’t see any homeless drinkers at the park.

I’m bored to death. I miss Clerkenwell.

Sources:

British History Online, http://www.british-history.ac.uk/report.aspx?compid=45101

Islington Now, http://islingtonnow.co.uk/?p=3029

The British Postal Museum Archive, http://postalheritage.org.uk/page/mountpleasant

Reffell Family History, http://www.reffell.org.uk/cemeteries/spafields.php

The British Postal Museum & Archive, http://www.postalheritage.org.uk/page/mount-pleasant

Local signposts

Biography:

Fernando Sdrigotti is a writer, urban photographer and film researcher. Born in Rosario, Argentina he has lived in London since the early noughties. His first book, Tríptico, was published in 2008; he is currently finishing his first collection of short stories, Ordinary Stories in Minor English and a novel in Spanish, Shetlag [sic]. At times he has been a full-time musician, part-time melancholic and occasional bohemian.

Like this:

Like Loading...