The most wonderful and the strongest things in the world, you know, are just the things which no one can see.

Charles Kingsley – The Water-Babies

We follow the river upstream, pressing on further than we’d ever walked before. We are a group of four boys, all aged eleven. We walk past the wide pool where, on previous occasions, we swam. Beyond that we pass the narrower stretches of river where, sometimes, we had lain on our bellies and reached under the side of the river bank to ‘tickle’ for trout. Not that we had ever caught any; but we had it on good authority that friends of friends, older boys usually, had successfully done so.

We walk on, enjoying the way the sunlight flickered through the trees which overhung the water. This part of the river is unfamiliar to us and the grass underfoot, lush and untrodden, suggests that few others ever walked this way. As we move along the riverbank the valley gradually narrows, the sides rising more steeply and the trees closing in; a twilight of shade. I feel uneasy, perhaps we all do, though none of us will admit it. We laugh and joke trying to lighten the oppressive mood that has crept up on us, but our efforts are laboured and soon we fall silent.

We walk on, perhaps two, maybe three miles, hearing only our own footsteps and the sounds of our breathing. Even the birds have ceased their singing. Then, rounding a bend in the river, we reach the end of the valley, or at least the end of all possibility of moving any further upriver.

Before us, like the massive rampart of some ancient fortress, is a high concrete wall. The wall stretches across the narrow neck of the valley, as if to pull both wooded sides together. We edge closer, wary of our proximity to the river which is now a narrow concrete channel. Dark and slow-moving, its waters hint at unspeakable depths. The wall rises before us, high and grey. Water trickles down its surface, and along its crest glower metal railings topped with barbed-wire.

We can walk forward no further, and with an unspoken agreement that we no longer wish to linger in this gloomy spot, we turn and retrace our footsteps. A brisk walk later we emerge once more into the world of warmth and light, and are able to enjoy again the sound of running water, bird song and the fragrance of the summer meadows which stretch out on both banks of the river.

Several days later I told my dad about our walk and asked him if he knew anything about the strange dam further up the valley from where we kids normally played by the river. He told me that we’d clearly walked a long way, almost as far as the next village, and that the dam was part of the perimeter of an old factory. The factory was dangerous, he told me, and we should keep well clear of it.

My friends and I did keep away and never walked as far as the dam again. In fact, it wasn’t long afterwards that we stopped playing by the river altogether. A boy called John, a friend of my older brother’s, got into an argument with another boy on the riverbank and stabbed him. The place seemed to lose its attraction to us after that.

My friends and I did keep away and never walked as far as the dam again. In fact, it wasn’t long afterwards that we stopped playing by the river altogether. A boy called John, a friend of my older brother’s, got into an argument with another boy on the riverbank and stabbed him. The place seemed to lose its attraction to us after that.

But that wasn’t quite the end of it. Through my childhood, and later into my teenage years, I picked up snippets of talk from listening-in on adult conversations. One thing that had really piqued my interest was hearing occasional references to the ‘bomb factory’. Was it a real place or just part of local folklore? I wasn’t sure, but people my parents knew seemed to be saying that they had once worked there.

A little later, when studying O Level Art at school, I developed an interest in architecture. I had a particular fascination at that time for a group of large art-deco houses on a road near our council estate. I loved the curved windows, the clean lines and the bold use of concrete. They were known as ‘the ICI houses’.

A little later, when studying O Level Art at school, I developed an interest in architecture. I had a particular fascination at that time for a group of large art-deco houses on a road near our council estate. I loved the curved windows, the clean lines and the bold use of concrete. They were known as ‘the ICI houses’.

Much later, when I was a student, I discovered that ICI ran a weapons research facility near my home town during World War Two. The ‘ICI houses’ were built for the senior managers and scientists from that facility. It was known in its planning phase as the X-Site and then, once constructed, as the Valley Works. But to the locals, in the spirit of calling a spade a bleeding shovel, it was the Bomb Factory.

* * *

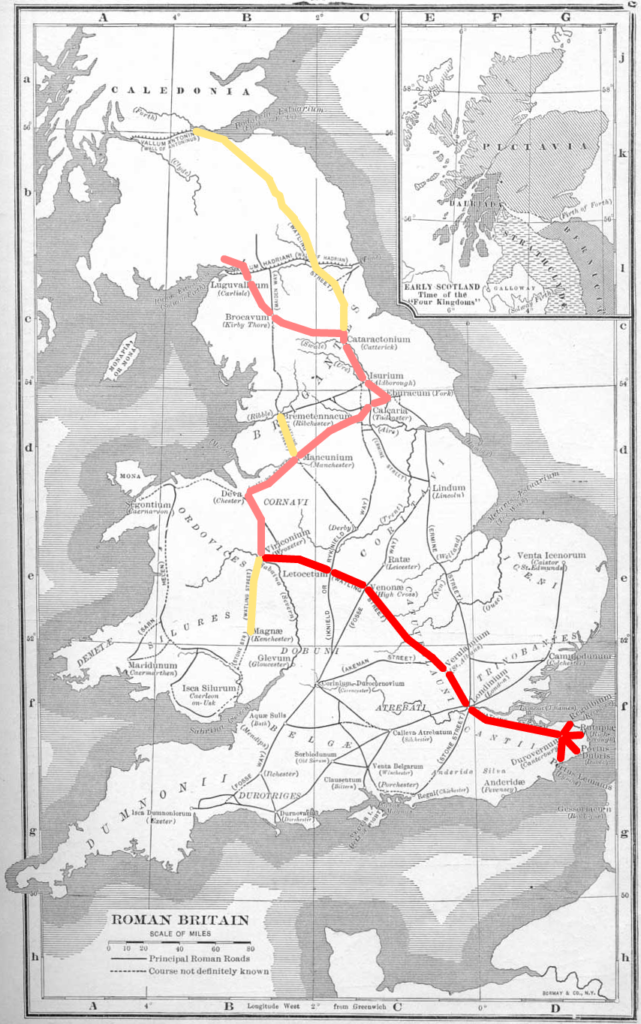

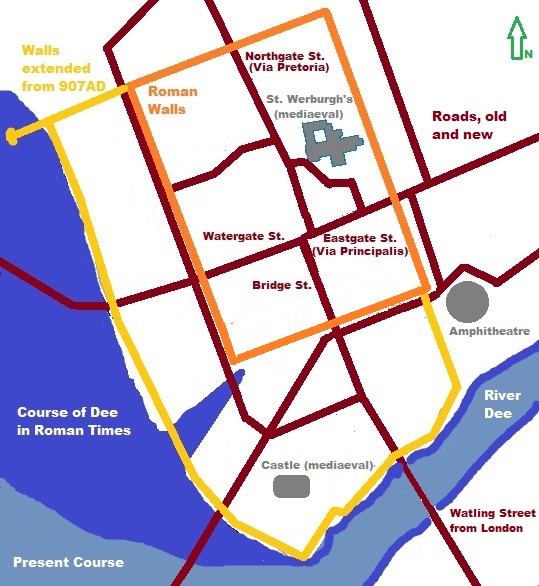

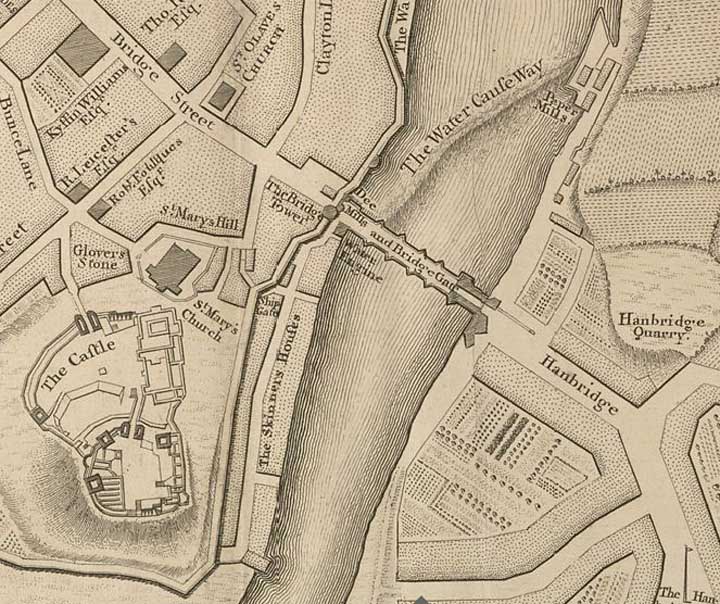

But the hills around here are hollow. Way back, even before the Romans came, the hills of Flintshire were mined for lead. The Romans expanded the workings and used Flintshire lead for their settlement at Deva (Chester). Later, during the time of Edward I, local lead was used for the construction of Builth Castle.

The industry was centred on the high ground of Halkyn Mountain, but over the centuries, it expanded north and south along the valley of the River Alyn (Welsh: Afon Alun). The section of the river valley around the village of Rhydymwyn is carved out of the underlying limestone and is pitted with underground caverns and chambers. And it is here, above ground and below, that the Valley Works was built in 1939.

But before that, in the nineteenth century, this stretch of the valley was already being developed by the Taylor family of nearby Coed Du Hall. Originally from Norwich, John Taylor was a landowner and mining engineer. He oversaw the expansion of lead mining along the Alyn Valley at Rhydymwyn and had a foundry built on the edge of the village.

But before that, in the nineteenth century, this stretch of the valley was already being developed by the Taylor family of nearby Coed Du Hall. Originally from Norwich, John Taylor was a landowner and mining engineer. He oversaw the expansion of lead mining along the Alyn Valley at Rhydymwyn and had a foundry built on the edge of the village.

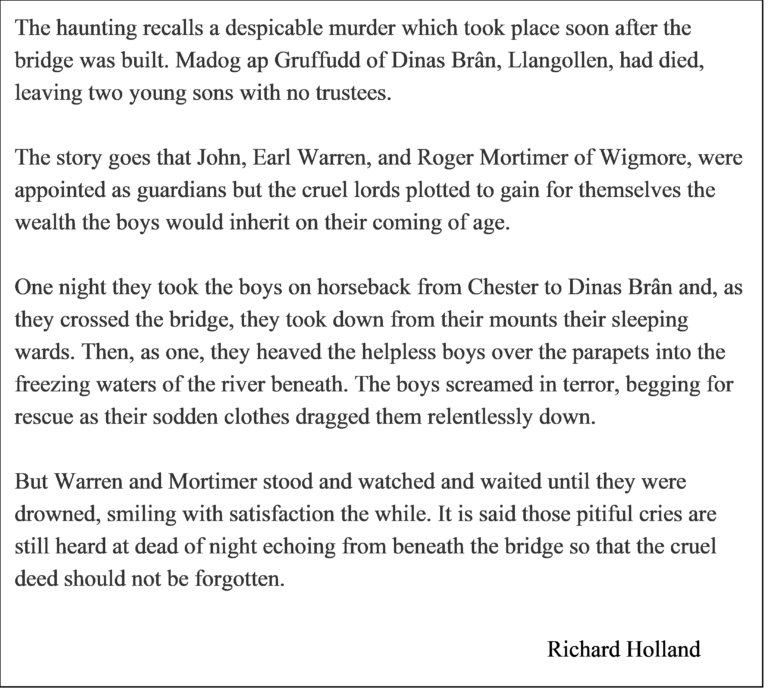

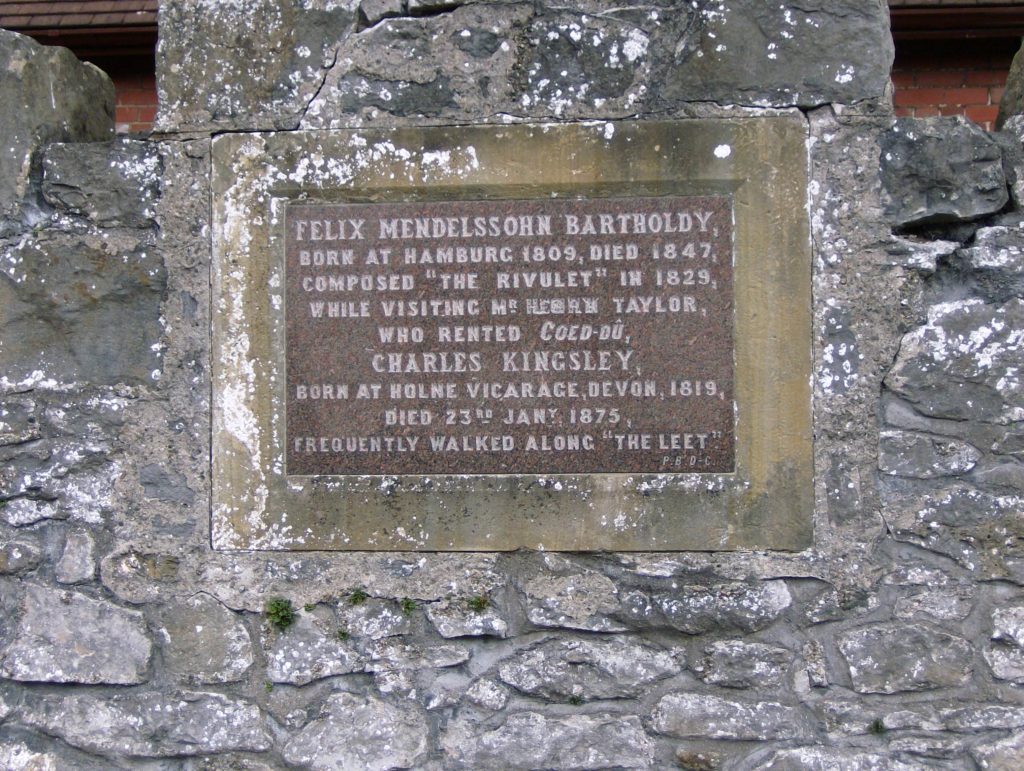

In 1829 the German composer Felix Mendelssohn made one of several visits to Britain and stayed with the Taylor family at Coed Du Hall. He had just completed some travels around Scotland planned to sail to Ireland from Holyhead, but the weather forced him to change his plans and stay with John Taylor, whom he had met in London.

In 1829 the German composer Felix Mendelssohn made one of several visits to Britain and stayed with the Taylor family at Coed Du Hall. He had just completed some travels around Scotland planned to sail to Ireland from Holyhead, but the weather forced him to change his plans and stay with John Taylor, whom he had met in London.

While at Coed Du he composed his Three Piano Caprices for Taylor’s three daughters, Anne, Susan and Honora. The third of the caprices, The Rivulet, is said to have been inspired by his walks with the sisters along the Alyn near Rhydymwyn. Mendelssohn’s time at Coed Du is marked by a plaque in the village.

Despite the legacy of almost two millennia of lead mining, the beauty that inspired Mendelssohn is still evident when one walks along the Alyn Valley today. Perhaps the odd industrial scar on the landscape, coupled with nature’s gradual but irresistible process of reabsorbing such aberrations, has its own kind of attraction. Gerard Manley Hopkins might have been referring to such places when he wrote about the idea of ‘dappled beauty’, whereas we use terms such as ‘liminal spaces’ or ‘marginal landscapes’ to describe such areas.

Some forty years after Mendelssohn’s time at Coed Du the writer and Christian Socialist, Charles Kingsley, was also a regular visitor to Rhydymwyn during the time when he was Canon of Chester Cathedral. It is believed that he enjoyed walking along the stretch of the Alyn known locally as the Leete and it is mentioned in passing in some of his nature writings. Some commentators have suggested that Kingsley river walks in the Rhydymwyn area inspired his most famous work, The Water-Babies, but this was in fact written some ten years before his time in Chester.

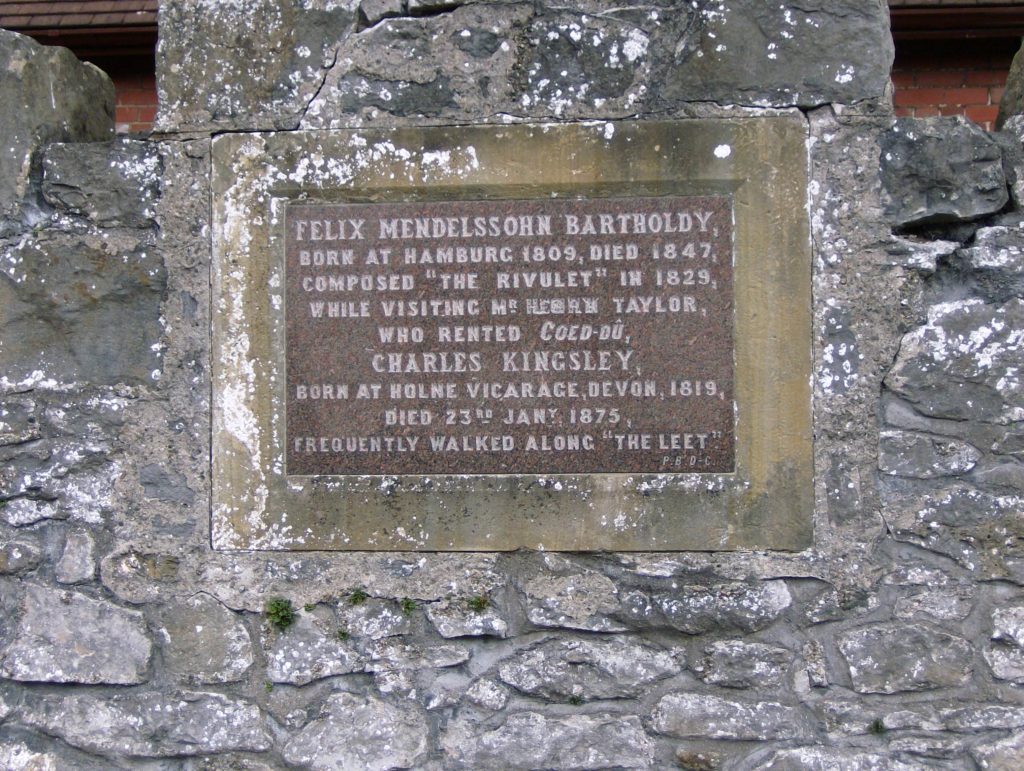

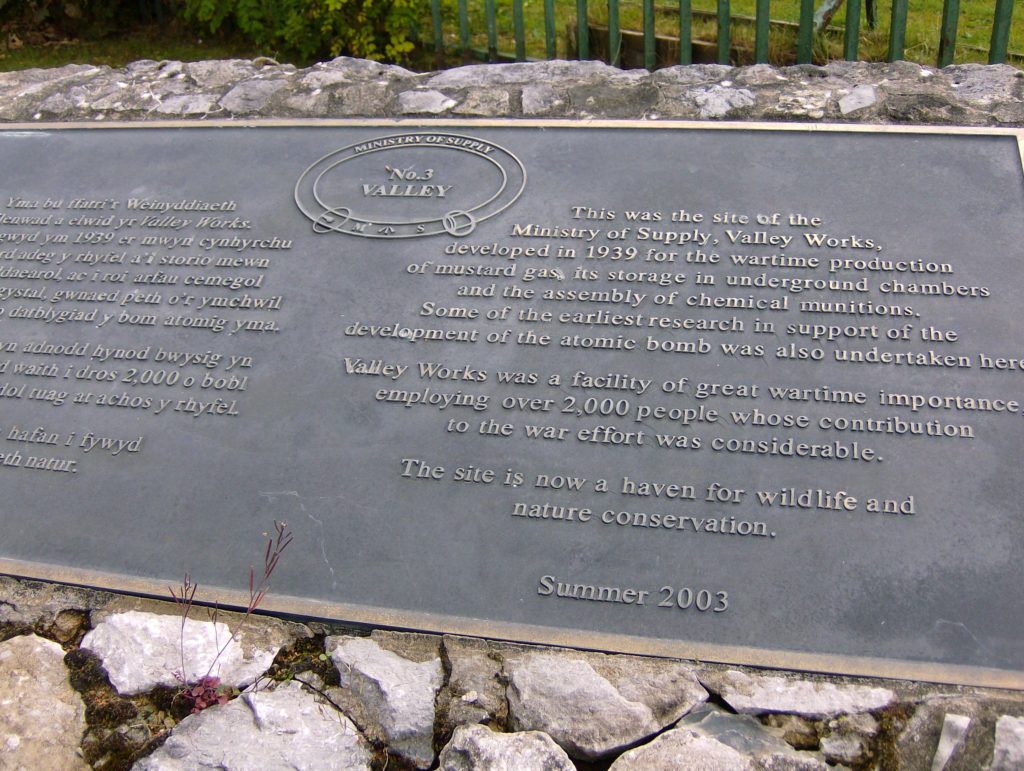

The lead mining industry in Flintshire went into a steady decline after the First World War due to difficulties in extracting the ore and the availability of cheaper imports. Mining in the Alyn Valley all but ceased during this period. By the eve of the Second World War, however, the Ministry of Supply came up with a new use for the site at Rhydymwyn; a use for which its flat valley floor, steep sides and extensive tunnels seemed to make it the perfect location. So in 1939 the Valley Works was established.

The lead mining industry in Flintshire went into a steady decline after the First World War due to difficulties in extracting the ore and the availability of cheaper imports. Mining in the Alyn Valley all but ceased during this period. By the eve of the Second World War, however, the Ministry of Supply came up with a new use for the site at Rhydymwyn; a use for which its flat valley floor, steep sides and extensive tunnels seemed to make it the perfect location. So in 1939 the Valley Works was established.

* * *

The Valley Works is now open to the public, though unless you are attending an organised open day you have to make contact first and set up your visit. It took several emails and a couple of phone calls before my visit was finally agreed. The site is now run by Defra, the government’s Department for Environment Food & Rural Affairs. The site manager’s biggest concern was whether or not I was a journalist: if I was from the press they’d have to get clearance from head office first.

Finally, on a weekday morning in September 2014, I arrived at the Valley Works for my scheduled visit. I introduced myself to the site manager, who didn’t seem to be particularly thrilled to see me. But I was handed over to one of his staff, who couldn’t have been more helpful. We chatted about the site and then he took me outside to help me get my bearings before he sent me on my way to wander around on my own for as long as I wished.

Away from the office my guide was able to apologise for the hassle I’d had trying to set up the visit. It was worth joining the Rhydymwyn Valley History Society, he advised, because I could then visit any time I wanted. But he cautioned me against asking too many ‘awkward questions’ as that was what had got a local Green Party activist excluded from the site. I don’t know exactly what his awkward questions were but, it seems to me, asking how any toxic residues on the site are dealt with is a pretty legitimate line of enquiry.

Away from the office my guide was able to apologise for the hassle I’d had trying to set up the visit. It was worth joining the Rhydymwyn Valley History Society, he advised, because I could then visit any time I wanted. But he cautioned me against asking too many ‘awkward questions’ as that was what had got a local Green Party activist excluded from the site. I don’t know exactly what his awkward questions were but, it seems to me, asking how any toxic residues on the site are dealt with is a pretty legitimate line of enquiry.

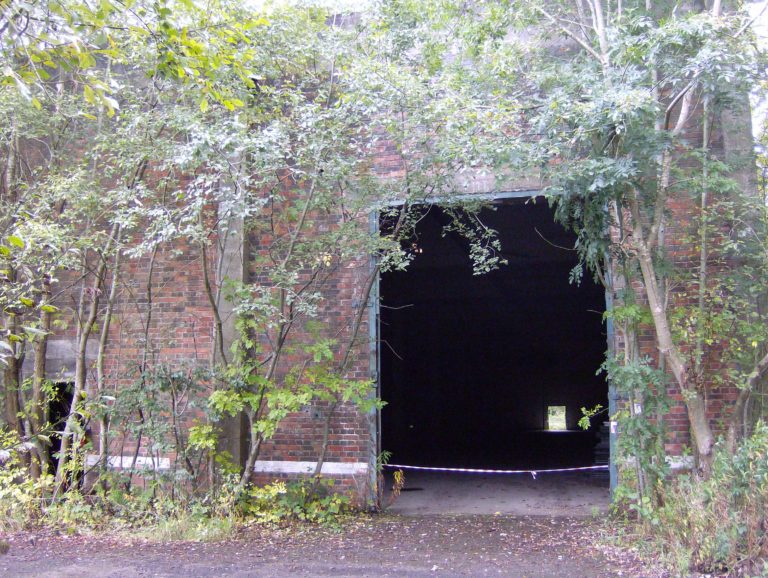

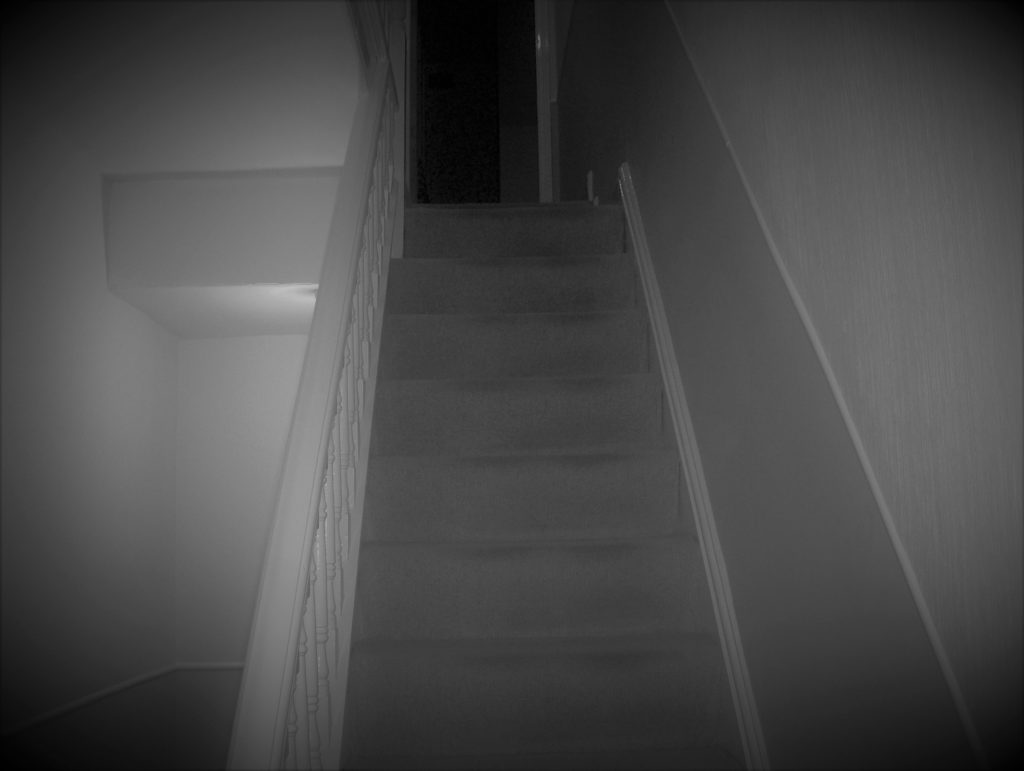

Before he left me to wander off on my own, my guide unlocked the thick, steel door to one of the underground storage tunnels to let me have a quick look inside from the entrance area. I was slightly disappointed as we could not walk very far into the tunnel, for ‘health and safety’ reasons, but I was able to gain a sense of the enormous scale of the underground workings at the site.

The Valley works site covers some 87 acres and, although much of this is taken up by the remains of ICI’s chemical weapons manufacturing and storage plant, it is also home to foxes, badgers, otters and rare plants. One section of low lying ground has been deliberately flooded to allow wetland plants and creatures to thrive. Previously lawned areas have been allowed to return to their natural cover of wild grasses and plants and once more provide an ideal habitat for a range of wildlife.

The Valley works site covers some 87 acres and, although much of this is taken up by the remains of ICI’s chemical weapons manufacturing and storage plant, it is also home to foxes, badgers, otters and rare plants. One section of low lying ground has been deliberately flooded to allow wetland plants and creatures to thrive. Previously lawned areas have been allowed to return to their natural cover of wild grasses and plants and once more provide an ideal habitat for a range of wildlife.

The use of chemical weapons in warfare had been banned by the Geneva Protocol of 1925. However, all the major powers still had stocks of such weapons and the capacity to produce more. Once war with Germany seemed inevitable in 1939, the government felt that Britain’s main chemical weapons capability, at the ICI plant in Runcorn on the Mersey, was too vulnerable to attack by enemy aircraft. The Ministry of Supply’s search for a new site resulted in Rhydymwyn, or X Site as it was referred to at this stage, being offered to ICI.

The use of chemical weapons in warfare had been banned by the Geneva Protocol of 1925. However, all the major powers still had stocks of such weapons and the capacity to produce more. Once war with Germany seemed inevitable in 1939, the government felt that Britain’s main chemical weapons capability, at the ICI plant in Runcorn on the Mersey, was too vulnerable to attack by enemy aircraft. The Ministry of Supply’s search for a new site resulted in Rhydymwyn, or X Site as it was referred to at this stage, being offered to ICI.

The advantage of the X Site was that it was situated in a narrow, steep-sided valley which made access for the bombers of the time very difficult. But, crucially, it was the deep tunnels in the valley sides that made Rhydymwyn such a good choice; even the largest bombs had no hope of penetrating through hundreds of feet of limestone.

The advantage of the X Site was that it was situated in a narrow, steep-sided valley which made access for the bombers of the time very difficult. But, crucially, it was the deep tunnels in the valley sides that made Rhydymwyn such a good choice; even the largest bombs had no hope of penetrating through hundreds of feet of limestone.

The site was never attacked but, my guide told me, one of the defence measures in place was a battery of smoke machines further up the valley. Should any enemy bombers approach, the smoke machines would be fired up filling the valley and surrounding land with smoke so that the planes could not get an accurate visual fix on the site.

At its height, production at the Valley Works engaged some two thousand workers. The chief product was mustard gas, both in its Runcol (HT) and Pyro (HS) forms. Pyro was the original mustard gas used in the First World War in shells and Runcol was a more recent version which could be transported by air as it had a lower freezing point. Both were capable of debilitating large numbers of troops and civilians:

In the form of gas or liquid, mustard agent attacks the skin, eyes, lungs and gastro-intestinal tract. Internal organs may also be injured, mainly blood-generating organs, as a result of mustard agent being taken up through the skin or lungs and transported into the body. The delayed effect is a characteristic of mustard agent. Mustard agent gives no immediate symptoms upon contact and consequently a delay of between two and twenty-four hours may occur before pain is felt and the victim becomes aware of what has happened. By then cell damage has already been caused.

Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons

Rhydymwyn was also involved in some of the early gas diffusion experiments that formed the basis for the Manhattan Project: the Allied nuclear bomb. Post-war the site played an important role in similar experiments that led to the development of a British nuclear weapon. Building 45, where these experiments took place, has been given somewhat dubious recognition by being awarded Grade II listed status in 2006. There is a strange irony that a building where so destructive a weapon was planned should be given special protection against inappropriate development.

Rhydymwyn was also involved in some of the early gas diffusion experiments that formed the basis for the Manhattan Project: the Allied nuclear bomb. Post-war the site played an important role in similar experiments that led to the development of a British nuclear weapon. Building 45, where these experiments took place, has been given somewhat dubious recognition by being awarded Grade II listed status in 2006. There is a strange irony that a building where so destructive a weapon was planned should be given special protection against inappropriate development.

The site is laid out as an elongated rectangle along the floor of the river valley and is pressed up against the limestone hills of the valley’s western side. During the construction phase of the X Site this section of the River Alyn was culverted to prevent it from flooding the works during winter. A spur of the Mold to Denbigh railway was also built to give direct rail access into the site.

I should mention that when I was researching the Valley Works, before and after my visit, I found the resources gathered by the Rhydymwyn Valley History Society invaluable. One interesting thing I discovered on their site was an archive of oral history from local people who had worked at the factory. I was astounded to find that one of the women whose wartime memories were recorded there was the mother of one of my childhood friends; Gerry’s Mum had once worked at the bomb factory and I had no idea!

I should mention that when I was researching the Valley Works, before and after my visit, I found the resources gathered by the Rhydymwyn Valley History Society invaluable. One interesting thing I discovered on their site was an archive of oral history from local people who had worked at the factory. I was astounded to find that one of the women whose wartime memories were recorded there was the mother of one of my childhood friends; Gerry’s Mum had once worked at the bomb factory and I had no idea!

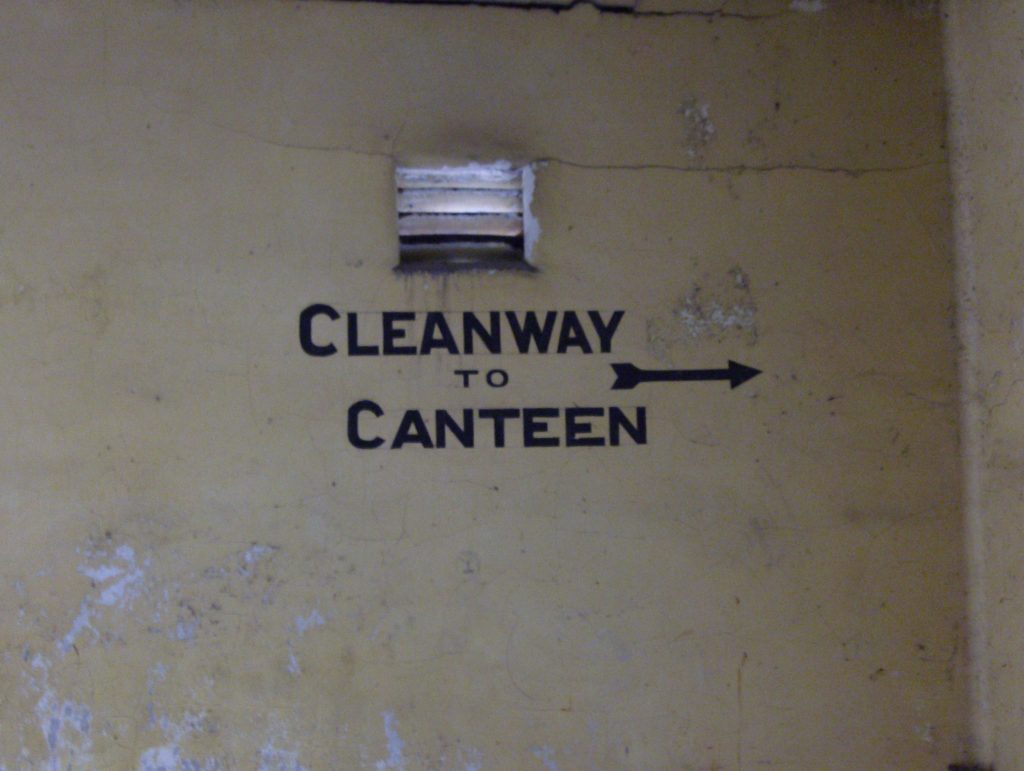

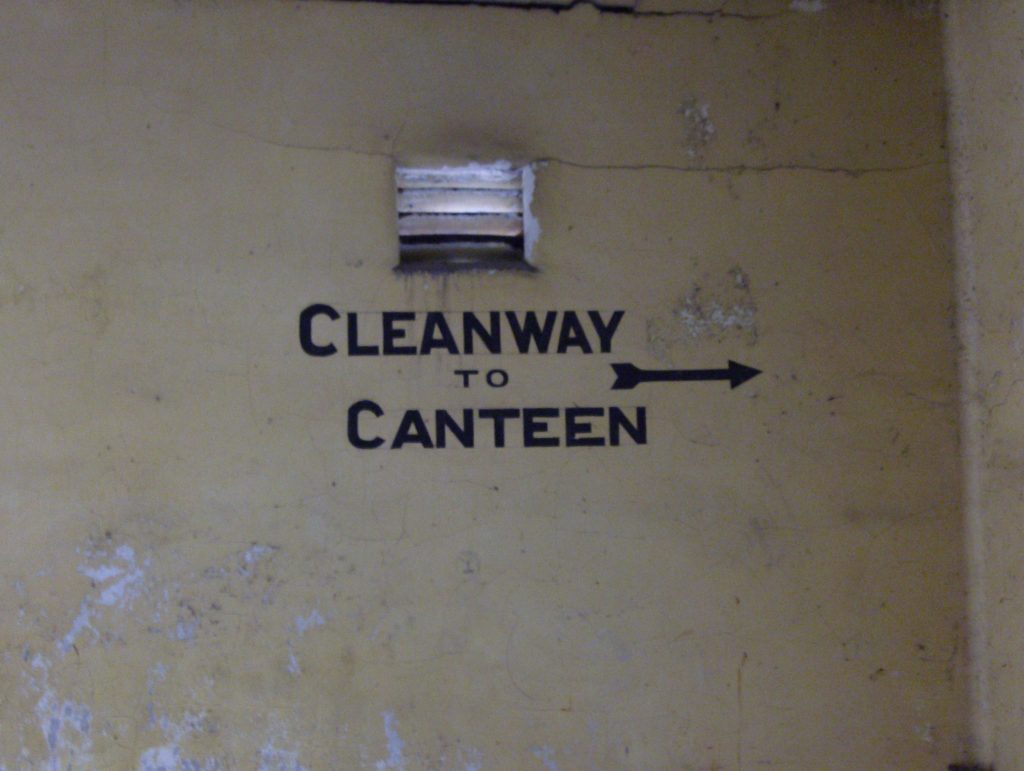

Left to wander without my guide, I walked around the Valley works site and noticed it was criss-crossed by a network of roads linking the various production buildings. I read later that a particular type of asphalt was used for these roads, one which was not prone to producing sparks.

Several dozen brick and concrete buildings still exist, some in a better state of repair than others. Essentially there were two classes of building: those involved in the production of mustard gas and those reserved for charging bombs and shells with the gas, together with explosives.

Several dozen brick and concrete buildings still exist, some in a better state of repair than others. Essentially there were two classes of building: those involved in the production of mustard gas and those reserved for charging bombs and shells with the gas, together with explosives.

The part of the works reserved for charging the shells comprises several small buildings rather than one large one. This is normal in arms manufacturing, to avoid one accidental explosion setting off a catastrophic chain reaction. During the war some of the completed weapons were shipped out to strategic stores in other parts of the country whilst others were stored underground in one or other of the three tunnels bored into the hillside.

Once the Second World War had ended, the production of mustard gas at the Valley Works ceased. Some stocks of Runcol and Pyro were buried at the site – dumped into pits and covered in bleach, which neutralises the active components in the liquid gas. I can’t help thinking, however, what toxic ingredients would have found their way into the local water course. The tunnels are the subject of all manner of conspiracy theories concerning their post-war use. The only function which has been officially confirmed is that they were the location of one of many strategic food stores in the Fifties and Sixties: high-energy foods to be used in the event of a national emergency.

As I wandered the site exploring the abandoned production buildings I came across other parts of the infrastructure of the works, including the site of a toxic burial pit, a pumping station and a railway platform. What struck me was that, although the Valley Works had been devoted to producing such nightmarish weapons, the site seemed so oddly normal. True it was a very pleasant autumn day with warm, still weather. But, had I not known the history of the site, all I would have seen would be a collection of decaying industrial buildings gradually being swallowed up once more by nature.

As I wandered the site exploring the abandoned production buildings I came across other parts of the infrastructure of the works, including the site of a toxic burial pit, a pumping station and a railway platform. What struck me was that, although the Valley Works had been devoted to producing such nightmarish weapons, the site seemed so oddly normal. True it was a very pleasant autumn day with warm, still weather. But, had I not known the history of the site, all I would have seen would be a collection of decaying industrial buildings gradually being swallowed up once more by nature.

One could be forgiven for pointing out the apparent dissonance between Mendelssohn’s sweet, pastoral Three Caprices of the nineteenth century and the later activities of this stretch of the river valley; its caverns piled high with poison gas and the river itself squeezed into a concrete coffin. But even in Mendelssohn’s time, and mainly at the behest of his host John Taylor, this landscape was already brutally scarred by mining and smelting and the men and women of the local workforce were being driven ever harder to increase productivity and reduce cost.

One could be forgiven for pointing out the apparent dissonance between Mendelssohn’s sweet, pastoral Three Caprices of the nineteenth century and the later activities of this stretch of the river valley; its caverns piled high with poison gas and the river itself squeezed into a concrete coffin. But even in Mendelssohn’s time, and mainly at the behest of his host John Taylor, this landscape was already brutally scarred by mining and smelting and the men and women of the local workforce were being driven ever harder to increase productivity and reduce cost.

Only at one point on my exploration of the Valley Works did I sense a change in the atmosphere. After the last of the buildings, at the far southern end of the site, the valley narrows and the trees close in. Here it was darker, cooler. And something else, something uncomfortably familiar. The site ends in a sturdy fence of metal railings; in fact this fence surrounds the whole site, some seven miles of it.

I stood at the fence, looking through its bars at the other side. Before me the land fell steeply away and below was a narrow meadow edging a stretch of river held within a concrete channel. Gazing over to my left I saw that the fence reached a corner and turned back on itself. Looking more closely I saw that the fence-line followed the culvert of the Alyn back into the site. I walked to the corner of the fence and looked down. I was standing to one side of the top of a high concrete dam. Water trickled down its grey, damp wall and gathered in the concrete channel below. Then looking up at me, or so I imagined, were four small boys, silent and wide-eyed.

This is a revised version of an essay by Bobby Seal first published at Unofficial Britain in February 2015. Unofficial Britain is a hub for unusual perspectives on the landscape of the British Isles, exploring the urban, the rural and those spaces in between. All words and images are produced by Bobby Seal. With grateful thanks to Rhydymwyn Valley History Society for all their assistance.

Like this:

Like Loading...

Tom Bolton sets out to explore this history by walking the entire length of the Essex coast; and, as we learn, it is a very long coastline, one that meanders drunkenly through creeks, mudflats and low-lying islands. But for Bolton, and his walking companion Jo Healy, the quest is not so much about history but about the present day. Geographically close to London, but far-removed in so many other ways, Essex is at once a point of access for those wishing to enter England peacefully and along its coast we are frequently reminded of its role as a key front line of defence against those who wished to invade. Crucially, the county was one of the heartlands of the pro-Brexit campaign with some 62.3% of those who took part in the 2016 referendum voting to leave the EU.

Tom Bolton sets out to explore this history by walking the entire length of the Essex coast; and, as we learn, it is a very long coastline, one that meanders drunkenly through creeks, mudflats and low-lying islands. But for Bolton, and his walking companion Jo Healy, the quest is not so much about history but about the present day. Geographically close to London, but far-removed in so many other ways, Essex is at once a point of access for those wishing to enter England peacefully and along its coast we are frequently reminded of its role as a key front line of defence against those who wished to invade. Crucially, the county was one of the heartlands of the pro-Brexit campaign with some 62.3% of those who took part in the 2016 referendum voting to leave the EU. Trans-Europe Express is not a systematic review of European architecture, but more an anthology of essays based on a series of journeys through the continent. It is also a lament for the way that Britain’s few brave attempts at European-style communal cityscapes has given way to our more ubiquitous privatisation of public spaces. Hatherley presents the cities of Łódź, Hamburg and Rotterdam as models, but also as lost opportunities.

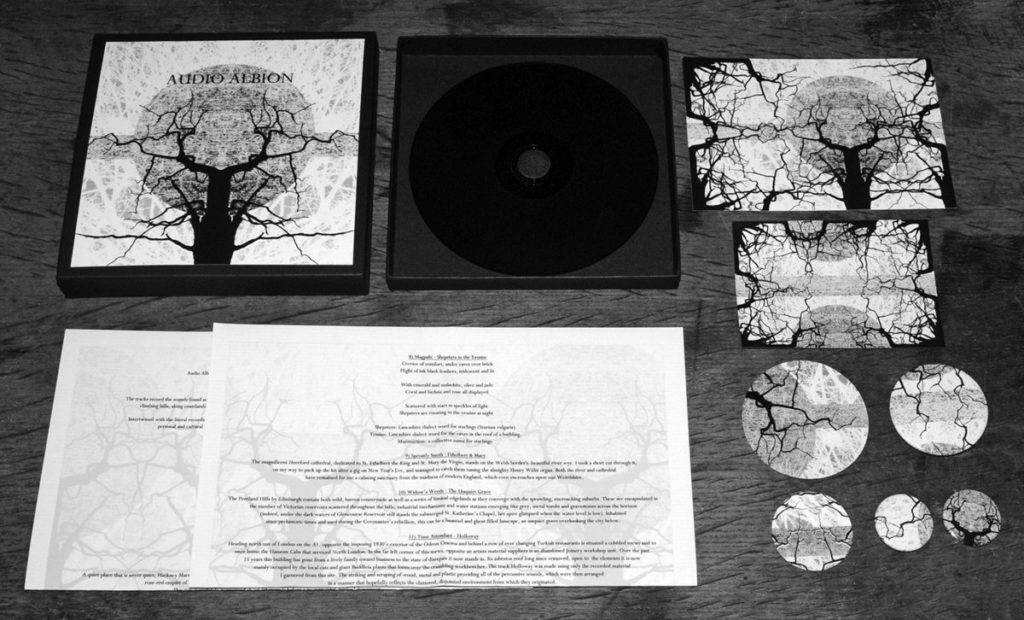

Trans-Europe Express is not a systematic review of European architecture, but more an anthology of essays based on a series of journeys through the continent. It is also a lament for the way that Britain’s few brave attempts at European-style communal cityscapes has given way to our more ubiquitous privatisation of public spaces. Hatherley presents the cities of Łódź, Hamburg and Rotterdam as models, but also as lost opportunities. Blending music and field recordings Audio Albion maps out the countryside and edgelands of this island and immerses us in the myths and legends that inhabit even the most mundane landscapes. The album comprises the work of fifteen different artists. But this is not a collection of tracks: it is a carefully constructed aural journey.

Blending music and field recordings Audio Albion maps out the countryside and edgelands of this island and immerses us in the myths and legends that inhabit even the most mundane landscapes. The album comprises the work of fifteen different artists. But this is not a collection of tracks: it is a carefully constructed aural journey. The ethereal opener My Danger gives way to the rockier, anthemic Figs and Flowers. The Man Who Says Goodbye follows with a joyous melody and lush instrumentation whereas Joy’s Reflection is Sorrow returns us inevitably to a more introspective mood. Sorrow’s Arrow and Secrets are achingly poignant and When Darkness Falls and Death and I are both as dark as their titles suggest.

The ethereal opener My Danger gives way to the rockier, anthemic Figs and Flowers. The Man Who Says Goodbye follows with a joyous melody and lush instrumentation whereas Joy’s Reflection is Sorrow returns us inevitably to a more introspective mood. Sorrow’s Arrow and Secrets are achingly poignant and When Darkness Falls and Death and I are both as dark as their titles suggest. Arcadia could so easily have ended up as nothing more than a cobbled-together and vaguely diverting compilation of archive footage of the British countryside; something that might find a comfortable home in the early evening schedule of BBC Four. Instead, with his inspired selection of footage and skilled editing, together with an atmospheric soundtrack by Adrian Utley and Will Gregory, Paul Wright has produced a folk-horror classic. A film that is all the more disturbing because it is not a work of fiction.

Arcadia could so easily have ended up as nothing more than a cobbled-together and vaguely diverting compilation of archive footage of the British countryside; something that might find a comfortable home in the early evening schedule of BBC Four. Instead, with his inspired selection of footage and skilled editing, together with an atmospheric soundtrack by Adrian Utley and Will Gregory, Paul Wright has produced a folk-horror classic. A film that is all the more disturbing because it is not a work of fiction.

Lynne Ramsay has directed some of the most innovative and compelling British films of the past two decades, most notably Ratcatcher and Morvern Callar. You Were Never Really Here is her first feature film since 2011’s We Need to Talk About Kevin and received awards at the 2017 Cannes Film Festival for Joaquin Phoenix’s central performance and Ramsay’s screenplay.

Lynne Ramsay has directed some of the most innovative and compelling British films of the past two decades, most notably Ratcatcher and Morvern Callar. You Were Never Really Here is her first feature film since 2011’s We Need to Talk About Kevin and received awards at the 2017 Cannes Film Festival for Joaquin Phoenix’s central performance and Ramsay’s screenplay.