As I lay asleep in Italy

There came a voice from over the Sea,

And with great power it forth led me

To walk in the visions of Poesy.

24th May 2004

Paper coin — that forgery

Of the title-deeds, which ye

Hold to something of the worth

Of the inheritance of Earth.

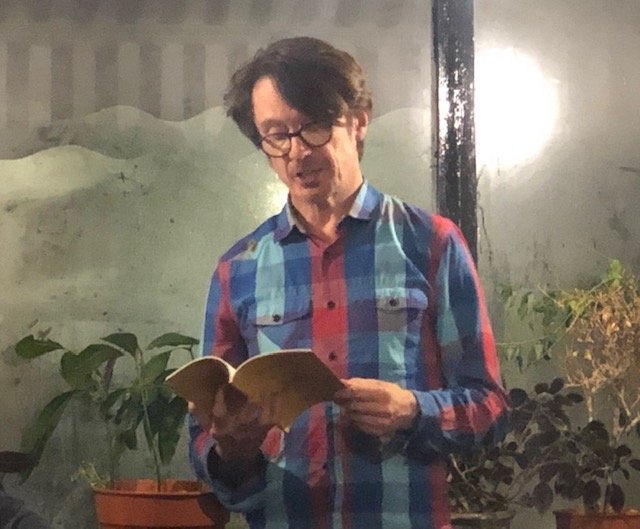

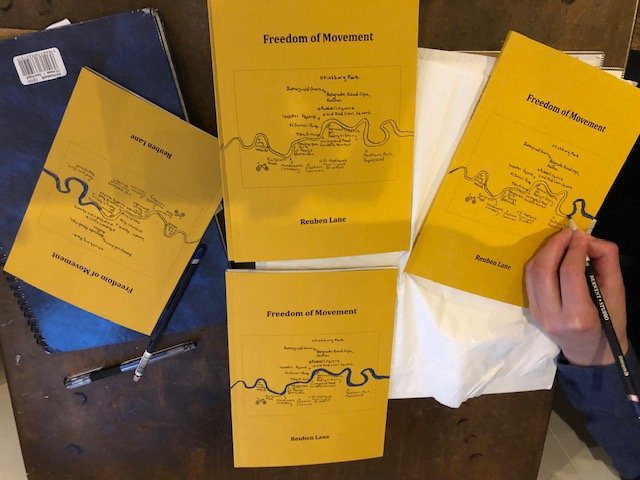

On this day in 2004 the Radisson Blu Edwardian Hotel opens in Manchester. It is located on the site of the former Free Trade Hall in Peter Street. I sit in the hotel’s reception area in September 2019 writing notes for what will become this piece. I have discovered that all that remains of the original building is the façade on Peter Street and a few artefacts incorporated into the hotel’s interior decor.

I feel out of place in this luxury hotel, especially as I feel weighed down by an awareness that such opulence is housed in a building that was originally constructed to celebrate the repeal of the Corn Laws. Meanwhile, something deeper cries out to me, for we are on a site where the infamous Peterloo Massacre took place and in a city synonymous with Chartism, the trade union movement and the work of Friedrich Engels. I shift uncomfortably on my plush seat in the hotel lobby. Perhaps this is the final triumph of Mammon; the story of the struggles of so many nameless men and women served up as local colour. As the Radisson’s marketing site puts it:

Finally, it was reborn in 2004 as a magnificent luxury 263 bedroom hotel, award winning restaurant and must visit spa. It retains its original façade, heritage and famous artefacts plus it is still at the heart of Manchester life. Located in Manchester’s historic Free Trade Hall and the original home to the Hallé Orchestra, Radisson Blu Edwardian Manchester has brought a new generation of award winning luxury to one of the city’s oldest and most iconic buildings over the past decade.

And as I sit and drink coffee and write up my notes on the train going home, the words of Shelley, written in fevered response to the Peterloo Massacre, come to mind. Just fragments really, ill-remembered fragments, but particularly the part that goes: ‘I met Murder on the way– / He had a mask like Castlereagh.’

19th May 1996

Let a vast assembly be,

And with great solemnity

Declare with measured words that ye

Are, as God has made ye, free–

After providing a home to the Hallé Orchestra for over a hundred years and serving as Manchester’s primary jazz and rock venue since the 1950s, the Free Trade Hall closed its doors for the last time in 1996. The interior had been destroyed by a Luftwaffe firebomb in 1940 but reopened in 1951 having been completely redesigned and rebuilt.

From the 1960s right through until the end of the century the main hall staged concerts by Louis Armstrong, Ella Fitzgerald, The Rolling Stones, Bob Dylan and many others. However, when the Hallé moved to the newly opened and state-of-the-art Bridgewater Hall in 1996 the patrons of the Free Trade Hall and local council decided that the older building was no longer required as a concert venue. It then stood empty and neglected for several years until it was acquired by developers who obtained planning permission to turn it into a luxury hotel.

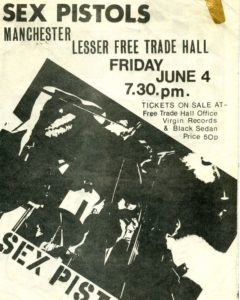

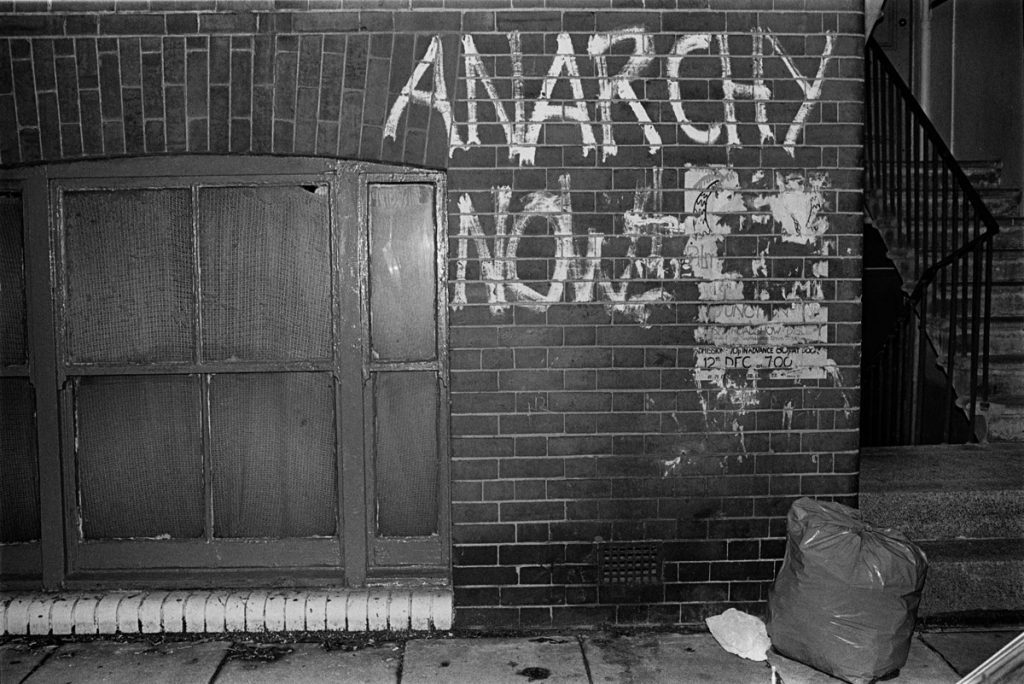

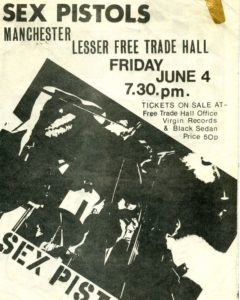

4th June 1976

Then all cried with one accord,

`Thou art King, and God, and Lord;

Anarchy, to thee we bow,

Be thy name made holy now!’

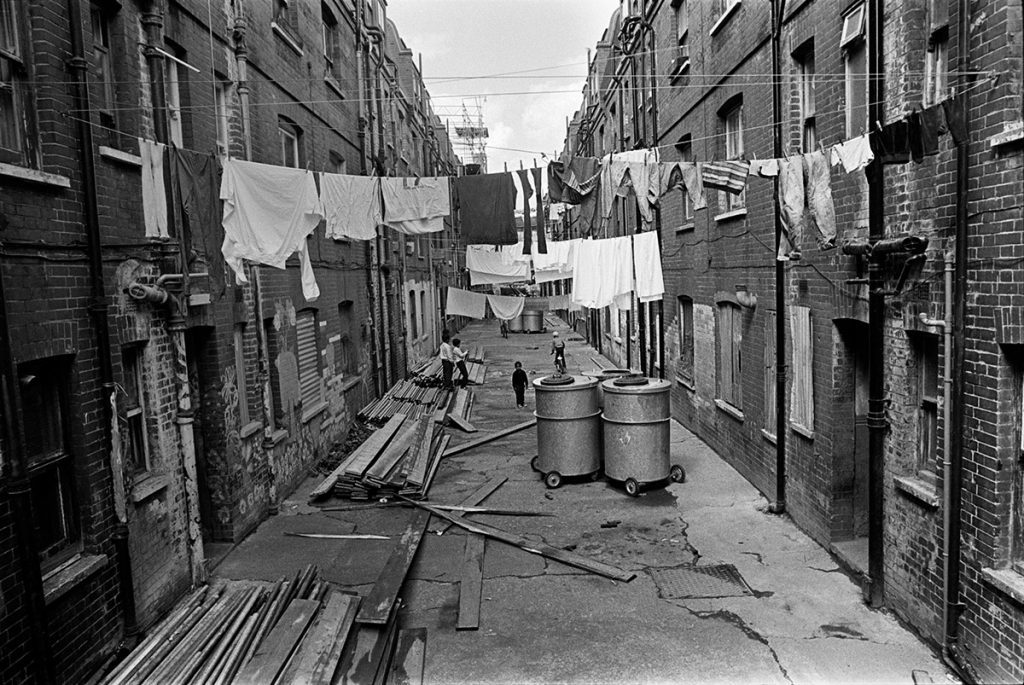

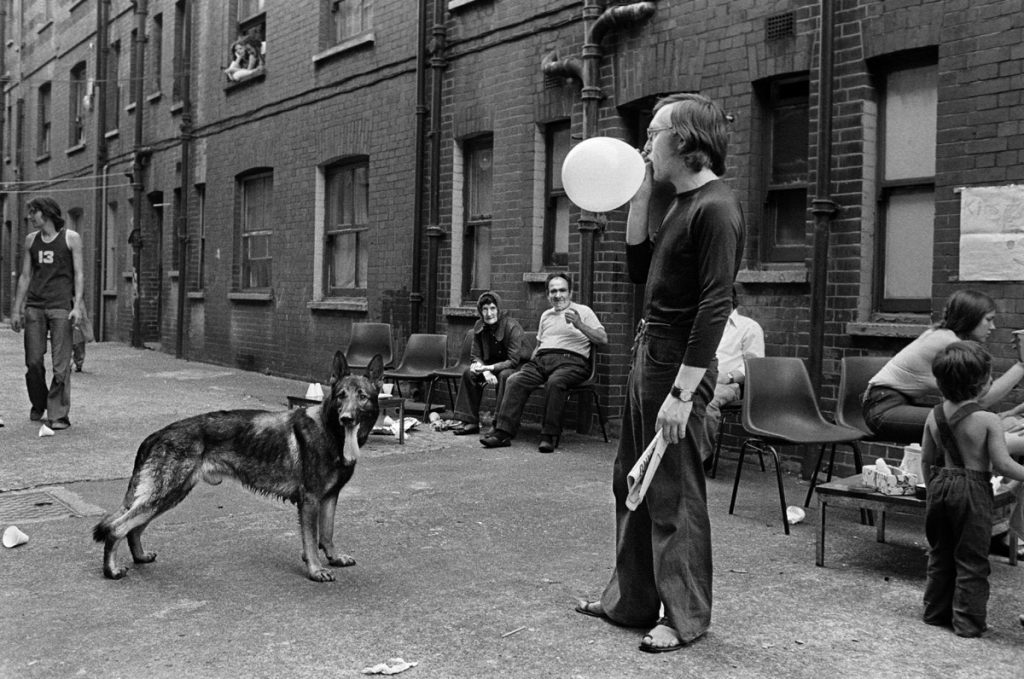

He travels to the gig by train from Chester with Steve. Steve’s leather jacket is so much cooler than his, with none of the elasticated fabric on its collar and cuffs that afflicts his own cheaper version. Steve works on the line at Vauxhall Motors, fitting radiators into a continuous procession of new Chevettes: five shifts a week, every week. Later he does an access course, goes to university and becomes a college lecturer. But that’s not part of this story.

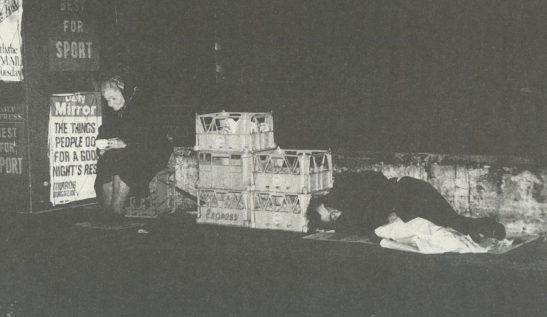

The gig isn’t even in the main hall; they are sent upstairs to a small, rectangular room that looks like it is normally used to store unwanted furniture. He only finds out afterwards, much later, that it is called the Lesser Free Trade Hall. There are only about fifty of them in the room. A few people manifest an awareness of there being something new in the air: a clutch of leather jackets, spiky hair and exaggerated eye make-up. he surreptitiously runs his fingers through his own newly cropped hair, wondering what product these lads and girls use to get those waxy spikes.

But most of the crowd are everyday prog-rock kids: all hair and flare. What strikes him most about all the people squeezed into this small room, however, is how polite and civilised everyone is. This is the case for prog-rockers and nascent punks alike. Even the weasel-faced bloke with the swastika arm-band smiles and says ‘Sorry mate’ when he accidentally bumps into his shoulder during the support band’s set.

The Pistols come on late, obviously. If anything, they seem to have gone backwards musically from when he saw them the previous year. The whole set is wilfully shambolic. But what they lack in musical finesse they more than make up for with attitude. Glen and Steve look dangerously wired and in a state that he can only describe as chronically pissed off. Meanwhile John snarls and slathers at the audience, trying to goad them into a response by making fun of the local accent.

The band’s approach is breathtakingly audacious. But are the Sex Pistols an expression of genius or a bunch of charlatans? Perhaps they are both. All he knows is that this gig is the spark that sets him on a decades-long trajectory of musical appreciation that embraces three-minute songs, simple chords and shitty local bands. It doesn’t inspire him to go out and buy a guitar, unlike the hundreds of others who claimed to be at the gig. But it does instil in him a belief in do-it-yourself creativity, an attitude which later comes to be called the punk ethic, and this ethic is something that continues to drive his writing and political attitudes to this day.

But perhaps this is a reflection constructed with the benefit of hindsight and a later conventional cultural narrative. On this day in 1976 it is just another gig, so much so that the two friends walk out of it before the end of the Sex Pistols’ set. It is all very exciting and enjoyable, but not worth missing their last train for. Even worse, the pubs are closed by the time they get back to Chester. Welcome to the seventies, kids.

10th December 1975

And Anarchy, the Skeleton,

Bowed and grinned to every one,

As well as if his education

Had cost ten millions to the nation.

But they have history, the Sex Pistols and him. The evening is billed as a Christmas party, but in reality it is just like any other band night at City Poly students’ union, an excuse to drink lots of beer to the accompaniment of some loud rock music. Brett Marvin and the Thunderbolts are top of the bill; he knows them from the London pub rock scene and they are the band he was looking forward to seeing.

Fairholt House is a weird venue: it comprises the upper three floors of an old office block on the corner of Whitechapel High Street and Commercial Street, but it is home to some of the best live music he’s ever heard. he was a naïve young lad from the provinces, only just turned eighteen, and Fairholt House was the alma mater of his education in the joys of sex, substances and radical politics.

A band called the Sex Pistols are third on the bill, he watches them as he stands next to the pinball machines by the bar. To be honest they don’t seem like anything special and certainly don’t strike him as the band who will shake rock to its roots within twelve months. They play too many cover versions and not enough original material for his liking, though he thinks the guitarist is pretty good. The singer acts like a complete twat on stage, though later, when he joins a few of the audience in the bar he seems like a decent bloke. He has to confess, however, that he’d forgotten the singer’s name by the next day.

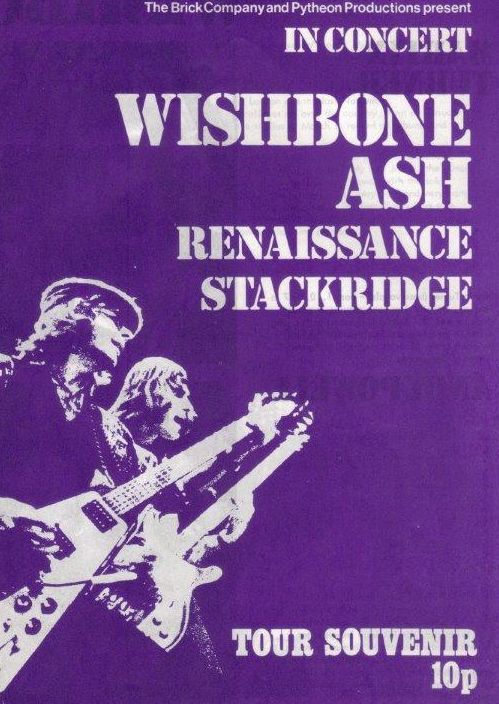

5th February 1972

Thou art not, as impostors say,

A shadow soon to pass away,

A superstition, and a name

Echoing from the cave of Fame.

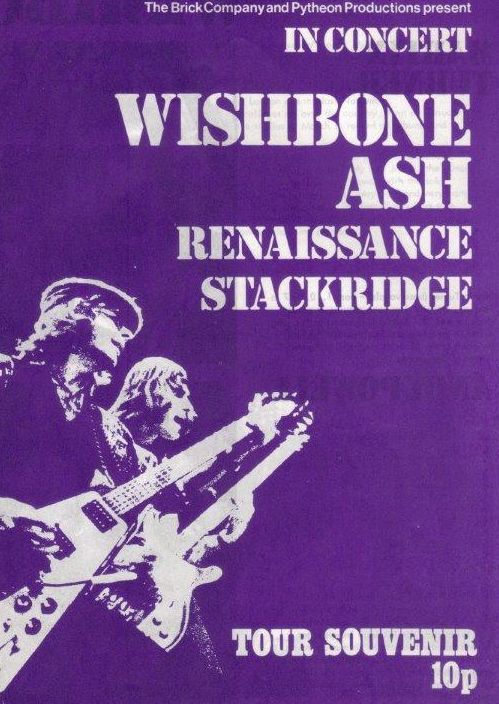

A pair of pale blue loons, white cheesecloth shirt and purple cotton jacket. So fucking cool. John and I had booked the coach and driver from the local bus depot and bought forty tickets by post from the Free Trade Hall box office. Neither of us had a bank account so we bought a postal order with the cash we’d collected from our friends, and friends of friends, at school. We ended up out of pocket because we hadn’t realised there would be a charge for the postal order, something the guy at the counter called ‘poundage’.

We are off to see Wishbone Ash at the Free Trade Hall in Manchester, my first big-name gig. We live in rural North Wales and John and I go on to organise trips to a dozen or more gigs during our time in the sixth form. We provide a coach and concert ticket package for local young people to go to see bands in Liverpool and Manchester. We always charge cost price; it never occurs to us that this was a potential money-making opportunity. We’re simply two sixteen-year-old lads who love music and want to go to see the bands we like with a gang of our friends from school.

So, for that couple of years before we all leave school we go to see the likes of Hawkwind, Stone the Crows, Yes, Emerson, Lake and Palmer, Rory Gallagher and many more. But Wishbone Ash, supported by Glencoe, in February 1972 was my first gig, and it was also the first time I became aware of the Free Trade Hall.

We wander the corridors, then hover in the bar and wonder whether we can pass for eighteen and be served with beer. Which of us looks the oldest, you me or Alan? All the time I gaze at other people’s clothes and hair and wonder what they make of mine. My hair is long, but too curly. I’m tall, but I have spots and can’t grow a beard. I breathe deeply and the air smells of beer, cigarettes and patchouli.

We enter the concert hall; it’s smaller than I’d expected, but I have to crane my neck right back to see the topmost balcony. Someone stands at the rail of the balcony immediately above us and he’s shouting drunkenly, demanding that the band come on stage right now. We laugh then, with dawning embarrassment, realise that he is one of our group.

We see the band outside, near a back entrance to the hall, after the gig and they sign our programmes and chat politely with us. But a crowd is gathering, and the band are clearly eager to get away as soon as they can. I return to the Free Trade Hall many times in subsequent years but, not until much later do I come to be aware of the history of the building and the site on which it sits.

17th May 1966

A rushing light of clouds and splendour,

A sense awakening and yet tender

Was heard and felt — and at its close

These words of joy and fear arose

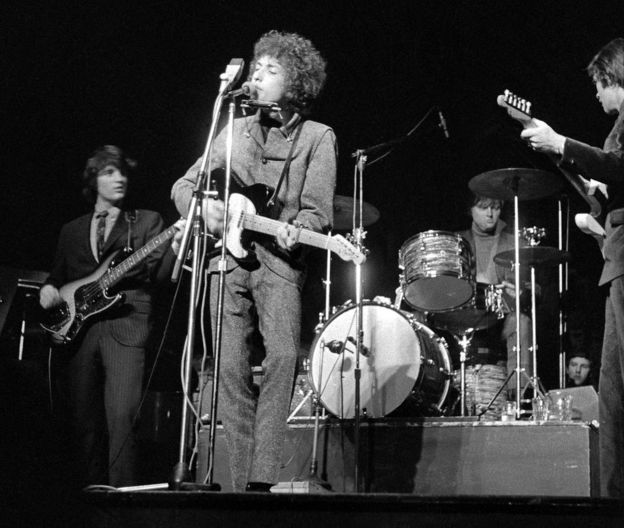

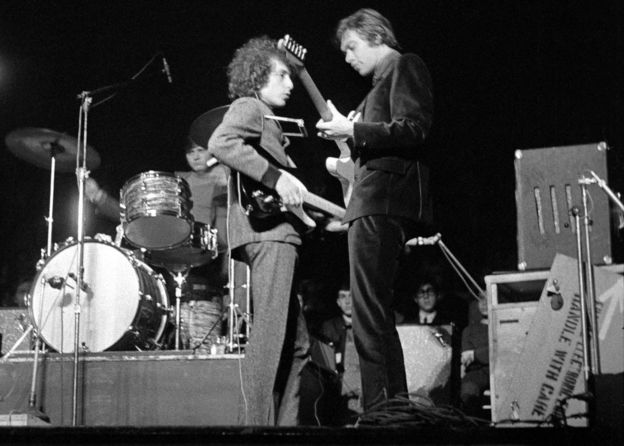

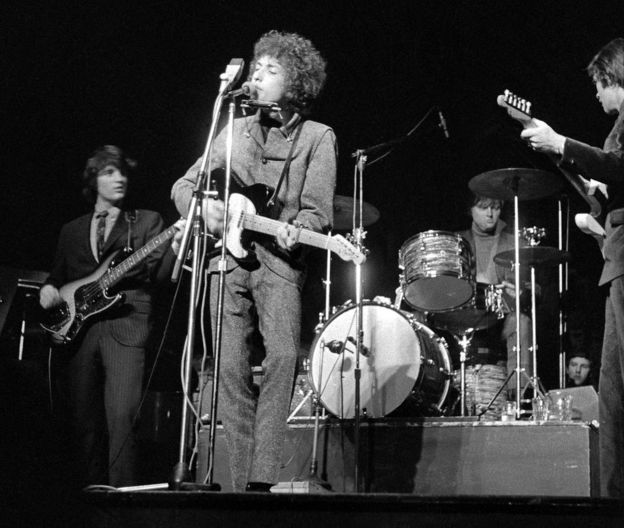

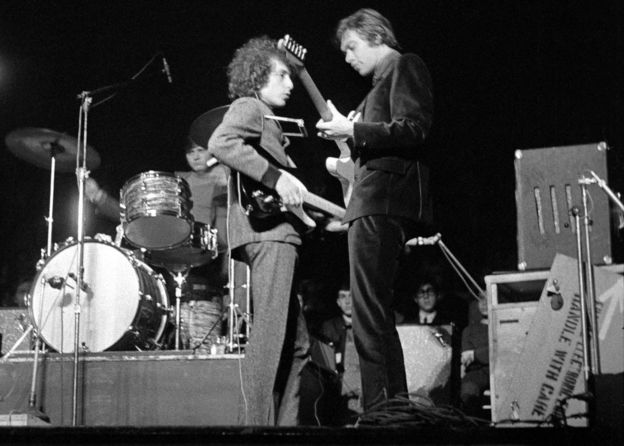

Bob Dylan played the Free Trade Hall towards the end of his world tour in May 1966. John Cordwell from Glossop managed to get tickets and attended the gig with several of his mates. They had a few pints at the Wagon and Horses on Southgate and then a couple more at the Free Trade Hall. Their seats were in the front row of the lower circle and they had an unimpeded view of the stage. The gig is infamous for widespread heckling from audience members and, in particular, one very loud shout of ‘Judas!’ from the circle which visibly angered Dylan. The controversy centred on Dylan’s recruiting of a rock band to back him in playing some of his new Highway 61 Revisited electric material. Hardline traditionalists saw this as a betrayal of Dylan’s folk roots and, throughout the 1966 tour, they were not shy in making their views known.

Things went well for the first half of the Manchester set, with Dylan alone on stage with an acoustic guitar playing his older songs. However, when Dylan and the band reappeared for the second half of the show and launched into newer material at an amplified volume many of his folk fans were not used to, the protests began.

The night goes down in rock history as the final dinosaur roar of folk traditionalists against the inevitable progression of musicians like Dylan. An objection to artists who wanted to widen the range of their creative expression and to experiment with other instruments and new musical arrangements. John Cordwell, on the other hand, while admitting that it was him who was heard to shout ‘Judas!’, suggests that he and the people around him were not objecting to the use of electric instruments, but were simply upset by the volume of Dylan’s second set and the poorly balanced sound that just did not work in a classical music venue like the Free Trade Hall.

13th October 1905

When between her and her foes

A mist, a light, an image rose,

Small at first, and weak, and frail

Like the vapour of a vale

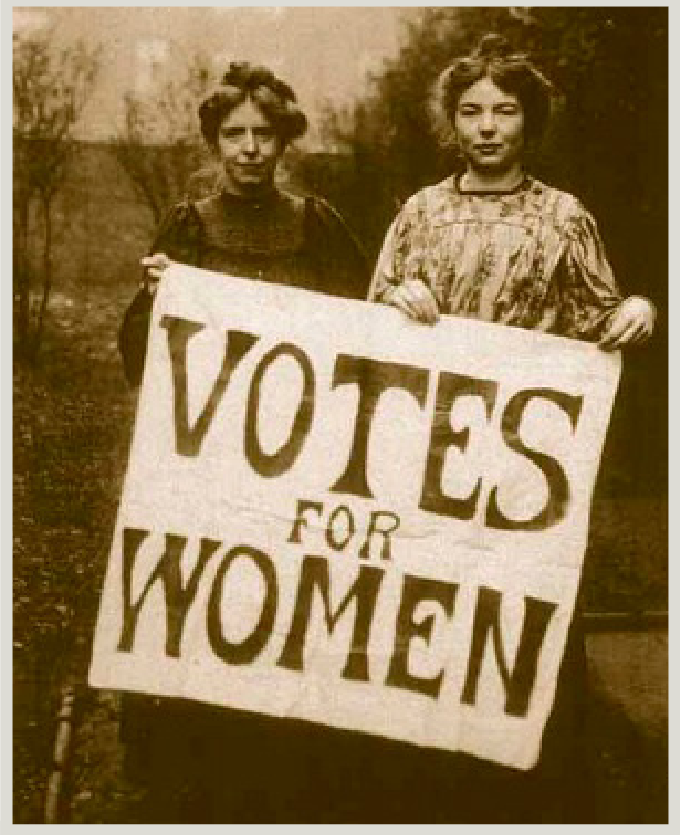

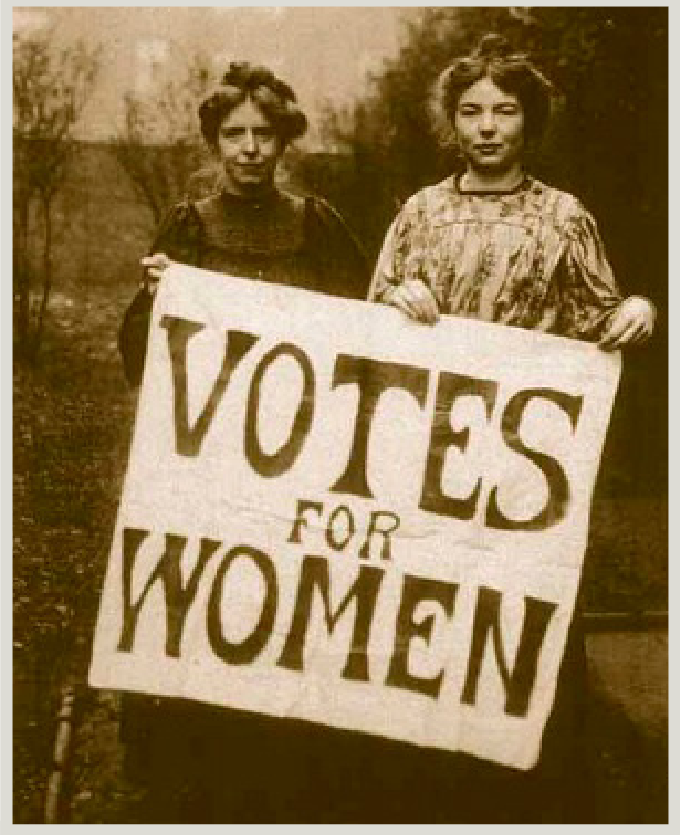

Christabel Pankhurst and Annie Kenney attend a Liberal Party rally at the Free Trade Hall. The Liberals are campaigning to be elected to office. Christabel and Annie plan to confront the main speaker, Sir Edward Grey, to prevent any backsliding on the party’s commitment to women’s suffrage.

At question time Christabel asks Grey: “If you are elected, will you do your best to make Woman Suffrage a Government measure?” Grey makes a joke, drawing the other men in his audience into a conspiracy of laughter, and avoids answering the question. Christabel persists, raising her voice. A policeman intervenes and tells her to be quiet. She and Annie are grabbed by police and stewards and forcibly ejected. Later they are arrested outside for alleged obstruction. It was to be 1928 before all women in Britain were granted the vote.

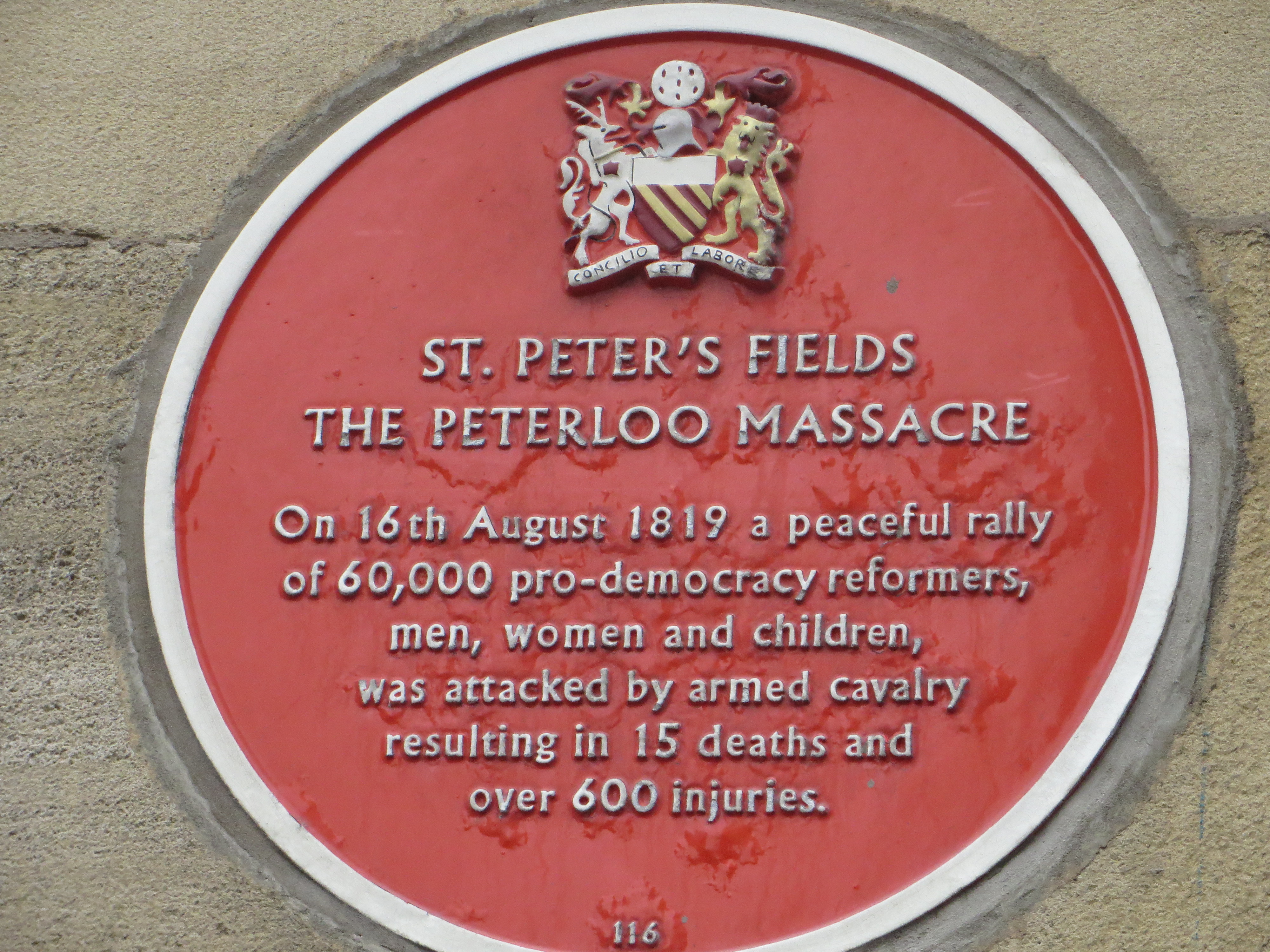

16th August 1819

Men of England, heirs of Glory,

Heroes of unwritten story,

Nurslings of one mighty Mother,

Hopes of her, and one another

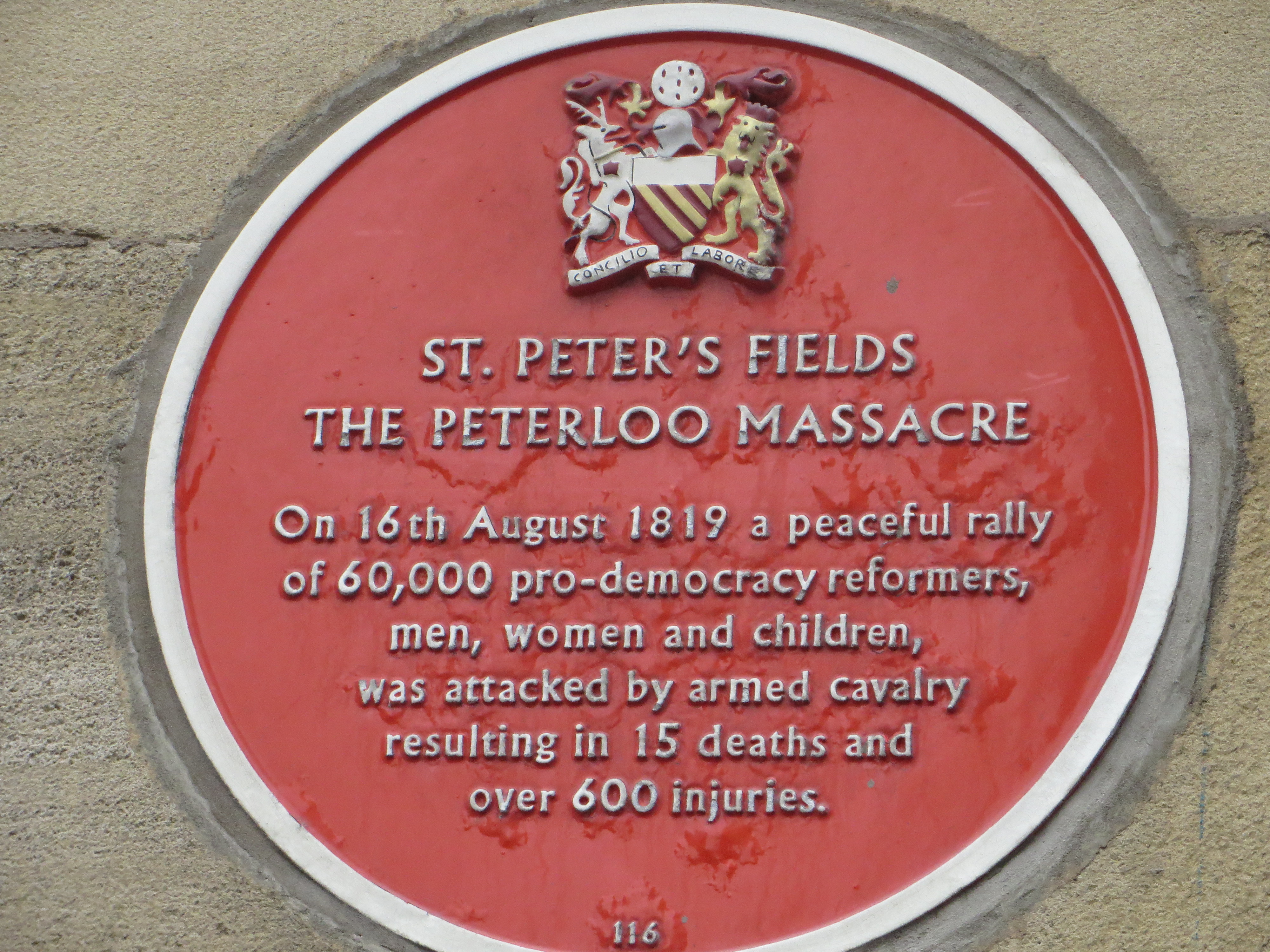

In March 1819 Manchester’s leading radicals formed a new organisation, the Manchester Patriotic Union Society, to campaign for political reform and universal suffrage. They organised a rally to take place at St Peter’s Field on 16th August 1819 and invited two of the most prominent national figures in the reform movement, Henry Hunt and Richard Carlile to speak.

In the build up to the rally, when it became clear that tens of thousands of people would attend, the authorities became fearful of a riot and an attempt at insurrection, despite the fact that the movement was sworn to peaceful mass action. On the day a group of local magistrates stationed themselves in a house overlooking the field and called up hundreds of special constables, regular soldiers and horsemen from the Cheshire Yeomanry and Manchester & Salford Yeomanry to be held in reserve.

The local campaigner and founder of the Manchester Female Reform Group, Mary Fildes, was one of the main speakers. Dressed all in white, she led a procession of women to the rally behind a white silk banner emblazoned with slogans demanding universal suffrage.

As the crowd at the rally swelled to an estimated fifty thousand the magistrates became alarmed and feared an outbreak of violence, although by all reports the gathering was good-humoured and orderly. They ordered in the Yeomanry to arrest Hunt and the other leaders and disperse the crowd. As the protesters closed ranks to protect the platform, the horsemen drew their sabres and tried to force their way through, slashing and trampling as they pushed on.

Hunt and several other leaders were arrested and the Yeomanry, local farmers and landowners, seemed particularly to target Mary Fildes, who presented a striking figure in her white dress. She received a sabre wound and was dragged away by special constables.

By the end of the day the Peterloo Massacre, as it became known, had resulted in the deaths of eighteen men, women and children and the wounding of at least five hundred others. The outcry over the massacre radicalised many thousands of others and led the creation of the Chartist Movement.

Mary Fildes survived her wound and later became a prominent activist in the Chartists. She ended her days as the landlady of the Shrewsbury Arms in Frodsham Street, Chester.

21st May 1856

And a mighty troop around,

With their trampling shook the ground,

Waving each a bloody sword,

For the service of their Lord.

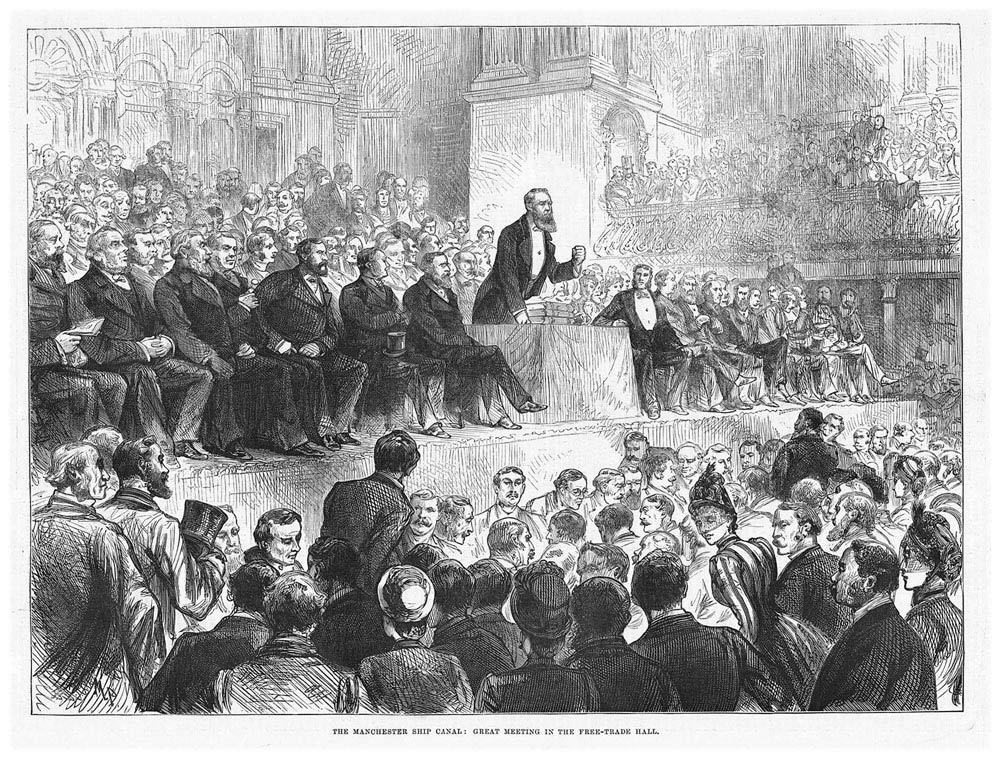

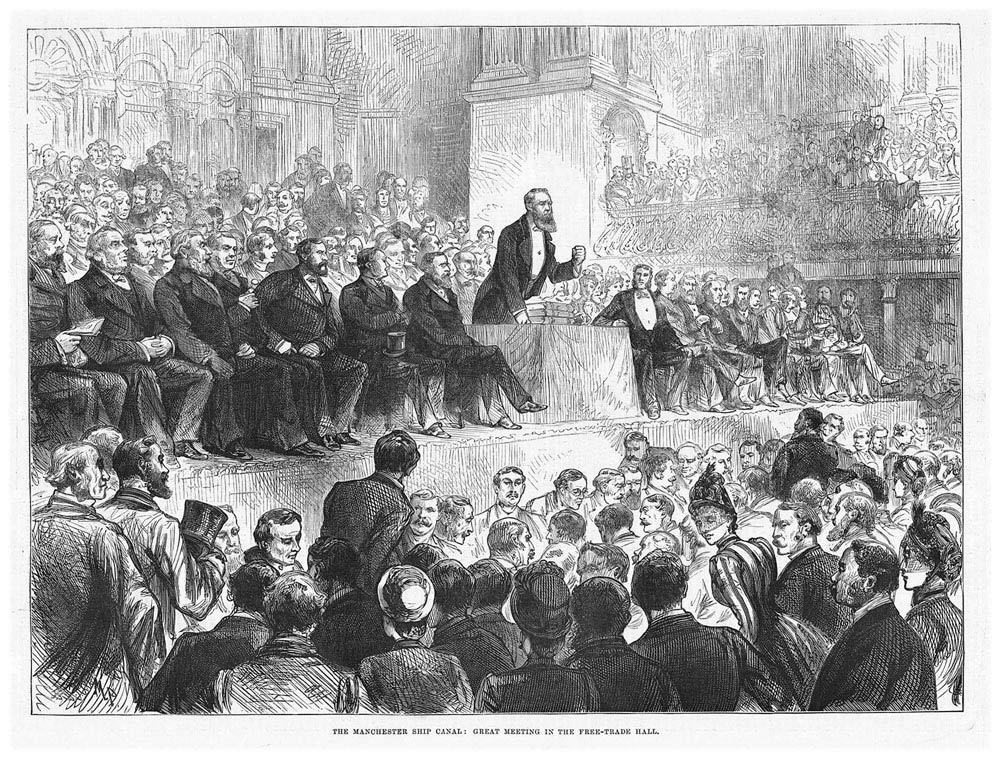

After the Peterloo Massacre, St Peter’s Field became a symbolic rallying point for radical causes in Manchester. Subsequent decades saw a number of gatherings by the Chartist movement and, later, the Anti-Corn Law League. The latter campaign built a wooden pavilion on the site in 1840.

Then, in 1853 and funded by public subscription, a new building for the St Peter’s Field site was designed by the architect, Edward Walters. The building was designed in the Italian Palazzo style and comprised two floors, a concealed roof and a nine-bay façade with carved stone figures celebrating Manchester and the county of Lancashire.

Thus, on 21st May 1856 the Free Trade Hall was opened. The purpose of the hall was to provide a setting for Manchester’s political meetings and rallies and, in 1858, it also became the home of the Hallé Orchestra.

Stepping outside the Free Trade Hall, or the Radisson Blu Edwardian Hotel as it now is, I walk along Southmill Street towards Manchester Central, formerly a railway station, now a conference venue. A ribbon of police vehicles are parked along the kerb outside and on the front concourse small groups of police officers stand around chatting and looking bored.

No one stops me so I walk past the police lines and nearer to the front entrance of the conference hall. The banner outside tells me why they are here: some sort of security practice-run, no doubt, for the big conference next week. The Tory Party are meeting here in the historic home of English radicalism. A Prime Minister appointed without a public vote and a government with no mandate and no majority meeting just two minutes from where, 150 years before, eighteen men, women and children gave their lives for the right to vote. Hear their voices still:

Rise like Lions after slumber

In unvanquishable number–

Shake your chains to earth like dew

Which in sleep had fallen on you–

Ye are many — they are few.’

- Lines of poetry quoted from The Masque of Anarchy (1819) by Percy Bysshe Shelley

- Sex Pistols gig picture – David Nolan

- Bob Dylan pictures – Mark Makin

- With thanks to Mike at Free Manchester Walking Tours

Like this:

Like Loading...