In fact and in fantasy, London had become a contested terrain: new commercial spaces and journalist practices, expanding networks of female philanthropy, and a range of public spectacles . . . enabled workingmen and women of many classes to challenge the traditional privileges of elite male spectators and to assert their presence in the public domain. In so doing they revised and reworked the dominant literary mappings of London to accommodate their own social practices and fantasies. The effect was a set of urban encounters far less polarised and far more interactive than those imagined by the great literary chroniclers of the metropolis.

(Judith R Walkowitz, City of Dreadful Delight: Narratives of Sexual Danger in Late-Victorian London)

Reading Mrs Dalloway again recently and writing the two Woolf-related pieces featured elsewhere on this blog set me thinking. At what point did the concept of the flâneuse emerge? And does the idea bear any relation to the reality that most women experience, or is it still just a literary device? In other words, to what degree, if any, do women today enjoy greater freedom to inhabit our urban spaces than that which was experienced by women a hundred years ago?

If we look at the early twentieth-century, we can see that women, in particular middle class women, incrementally gained a range of new freedoms; the freedom to walk alone in certain districts, at least during the hours of daylight, the freedom to work, within certain prescribed limits, and the freedom to shop – to wander through the commercial districts of major cities in order to look, to compare and to buy. Working-class women had always been free to wander the streets of the city, provided their perambulations were strictly related to their work or family responsibilities. Women who were out after dark, walking down the wrong street, or even walking at too leisurely a pace risked being subject to assumptions about their sexual availability. From Victorian times onwards, women’s participation in the life of the city gradually moved from the domestic to the public setting.

This increase in freedom of mobility for women, especially that of middle-class women, was in essence a metropolitan phenomenon – the new woman, the working girl, the female shopper; all became growing types of female presence in the modern city. Though clearly bounded by the demands of employers and commerce, this nonetheless represents a growth in freedom for women. Previously the streets had been the realm only of men, or of women escorted by men, and of women who had to resort to prostitution in order to survive. But the early twentieth-century saw an improvement to policing and street lighting in central London, the extension of the underground system and a greater prevalence of bicycles. This led to increased freedom of movement for middle class women. But even for middle class women, there were limits to how far they could push against the boundaries of entrenched attitudes.

This change, this increase in women’s freedom to wander through the city, is reflected in the fiction of the time: Katherine Mansfield, Dorothy Richardson and Virginia Woolf all portray female characters who have ready access to the streets of the metropolis in a way unknown to previous generations of women. Female characters from starkly different backgrounds – Ada Moss, the struggling actress forced into occasional prostitution in Mansfield’s Pictures, Miriam Henderson, the respectable working girl and autodidact in Richardson’s Pilgrimage and the wealthy politician’s wife, Clarissa Dalloway, in Woolf’s Mrs Dalloway – are all depicted as being able to enjoy the freedom to walk through London alone.The question then is did these, albeit limited, freedoms that were allowed to women, and the writers who reflected their lives in their fiction, create the female equivalent of the male flâneur; in other words, did early modernism bring with it the creation of a recognisable flâneuse?

Shopping and the Commodification of Flânerie

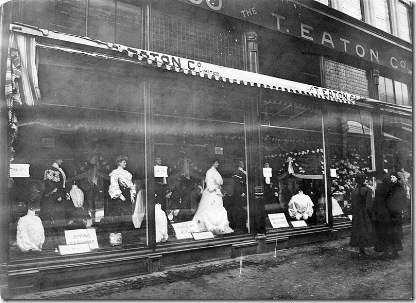

Benjamin’s archetypal flâneur wandered the Parisian shopping arcades. London had its own arcades, modelled on those of Paris, but these did not become the haunt of the flâneuse. Although, in the early twentieth-century, women were increasingly able to shop without being accompanied by men, it was the new department stores rather than the arcades which they made their own. Department stores, women discovered, invite flânerie. The department store, like the arcade before it, constructed fantasy worlds for itinerant lookers. But unlike the arcade, it offered a protected site for the empowered gaze of the flâneuse. The existence of the flâneuse was only possible when a woman could wander the city on her own, a freedom linked to the privilege of shopping on her own.

Department stores became central fixtures in most large cities by the early years of the century; and from the start they employed female sales assistants, allowing women to be both buyers and sellers and not just another commodity for the enjoyment of the male gaze. But with this freedom came another form of commodification, this time at the hands of the advertisers and marketing agents. Judith Walkowitz suggests that many male commentators of the time wrapped up misogyny in a cloak of moral objection to market culture by casting it as ‘sordid and feminized’.

Women enjoyed new freedoms from these changes to the city centre, but the driving force was the market and not ideology; retailers quickly learned to target window displays and advertising at the female eye. There was new mobility for some women, but it fell far short of that enjoyed by the male flâneur; the freedom of the department store flâneuse is, after all, regulated by the male department store manager.

Prostitution and the Tyranny of Public Space

Thus in the public arena, the streets of the city, women are prey to the harassment of male optical gratification. Women cannot simply walk, they do not stroll, they certainly do not loiter. They are in public with a function, such as is provided by markets and shops and meeting children.

(Chris Jenks (ed), Visual Culture)

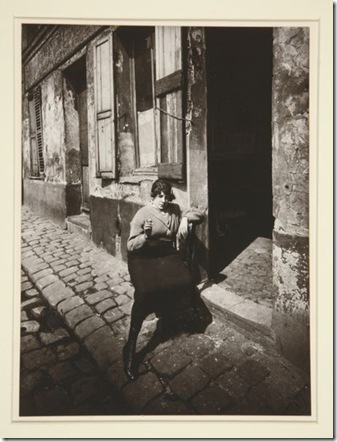

In some ways, despite the limitations imposed by the prevailing culture, women have nonetheless always been able to take part in urban observation. But working-class women, who effectively had the greater freedom to roam, in daylight at least, were the least likely group to have their observations recorded. Therefore, it was with the development of modernist writing, particularly in the works of Woolf and Richardson, that women were able to chronicle these observations. Almost all of Benjamin’s city figures were male – the flâneur, the gambler, the rag-picker. The one exception is the prostitute, or streetwalker. As Judith Walkowitz puts it:

The prostitute was the quintessential female figure of the urban scene . . . for men as well as women, the prostitute was a central spectacle in a set of urban encounters and fantasies.

(Judith R Walkowitz, City of Dreadful Delight: Narratives of Sexual Danger in Late-Victorian London)

Prostitution was indeed the female version of flânerie, which serves only to emphasise the inequality of gender differences in this era. The male flâneur was simply a man who loitered on the streets; but women who loitered risked being seen as prostitutes, streetwalkers, or les grandes horizontalesas they were known in nineteenth-century Paris.

The image of the prostitute, the most significant female image in The Arcades Project, is the embodiment of the prevailing male attitude to women at this time. Benjamin links together prostitution and gambling as the two sides of alienated sexual desire:

for in the bordello and gaming hall it is the same, most sinful delight: to insert fate within desire, and this, not desire itself, is to be condemned.

In a time when the city streets were the domain of men, any woman walking alone in a public place was viewed as a fallen woman. Whatever her position or motivation, she invariably functioned as a projection of the male loiterer’s alienation or as a symbol of a form of social ‘contamination’ that had to be purged. In either case she is objectified.

Prostitution reflects the economic relationship of women and men. But, argues Benjamin, wrapped up in that relationship are also elements of fantasy, desire, pleasure, anxiety, guilt, shame, regulation and exploitation. Of particular interest to Benjamin is the ‘gaze’ of the customer upon the prostitute; a subjectively masculine gaze which tells us it is acceptable for men to gaze at women, but not the reverse. But, counters Walkowitz, male sensibilities were threatened by the fact that the prostitute did gaze back: in a look that was ‘audacious, unflinching’.

Indeed, there may well be a link between flânerie and voyeurism: when the flâneur absorbs the city visually he does so on the basis of a sense of entitlement; he acts as if he owns the city; which, in terms of the power held by his gender at least, he does. The flâneuse, in literature and on our streets, joyfully subverts this norm.

Images

Eaton’s Department Store 1920s (out of copyright)

Streetwalker by Eugene Atget 1920s (out of copyright)

I think even though urban spaces undeniably belong to men, in a way we’re not in a position to know if there have been more flaneuses, real or fictional. Even if there have been, chances are they will have been written out of history, like countless women in other fields, or if their writings or their histories survived, they wouldn’t be seen as flaneuses but they’d be dismissed as “women’s interest” or similar. Which also happened and still happens to countless women. And even now with women considerably more free to wander (dangers aside), there’s still sometimes the claim that the flaneur, the drifter and the wanderer was *and still is* predominantly a man, so the two problems above haven’t gone away yet. So I believe that yes, we are more free now to wander and inhabit spaces (well, to some extend anyway- men still do a good job at telling us the world- and our bodies- are not ours), but are we seen as flaneuses, even if we do wander and write about it? Or even, are we only seen as flaneuses if we explicitly claim the title ourselves?

The question is indeed much more complex than my piece seems to imply – and I think the answer is ‘yes’, ‘no’ and all the gradations in between! But it’s the idea of the flâneuse that’s so very important. The idea of the flâneuse undermines the appropriation of public space by one gender and challenges the creeping privatisation of that space by corporate interests.