I asked my friend Will to join me on this walk. Will has lived in Wrexham for most of his life and I hoped he could put a personal perspective on some of the places I planned to explore.

Ever since I moved to Wrexham I’ve been aware of the town’s connection with the land-owning Cunliffe family of Acton Hall. The house was demolished many years ago, but the name lives on in the guise of Wrexham’s Acton suburb. Part of the parkland previously surrounding the hall now forms a public park. I sometimes run in this park, Acton Park, and I’ve enjoyed the odd pint in the nearby pub of the same name.

The thing I was not aware of until recently, however, was Acton Hall’s connection with George Jeffreys, the so-called ‘Hanging Judge’. Jeffreys was born at Acton Hall in 1645 and, after reading law at Cambridge and training at the Inner Temple, became James II’s Lord Chancellor in 1685.

He is infamous for presiding over the Taunton ‘Bloody Assizes’ of 1685 in which more than 160 alleged participants in the Monmouth Rebellion were executed. Will recalls seeing Patrick Troughton play Judge Jeffreys in a 1960s television dramatization of Lorna Doone, which I guess gives Acton Hall an extremely tenuous Doctor Who connection too.

We start our walk in Westminster Drive where Will points out the yellow fire hydrant post which, back in the 1970s, he and his childhood friends regularly used in order to climb over the fence into the school playing field to play football. This sports ground, known locally as the Nine Acre Field, was once part of the parklands of Acton Hall until it was purchased by the local Council just after Second World War. Westminster Drive, incidentally, translates into Welsh as Rhodfa San Steffan, an interesting reference to Westminster’s St Stephen’s Hall.

Walking along Chester Road we soon come to one the few remaining parts of the fabric of Acton Hall. The imposing neo-classical gateway marooned at the edge of a modern housing development which was once the main entrance to Acton Hall. It was built in 1820 at the behest of Sir Foster Cunliffe whose family bought the hall in the late eighteenth-century and remained there until 1917.

The symbol of the Cunliffe family is the greyhound: it features on their family crest and is also now used as the emblem of the Wrexham Area Civic Society. The original gateway to the hall had four wooden greyhounds mounted on its top. One disappeared when the US army were stationed at Acton Hall in World War Two and another was destroyed by vandals in 1964. The present greyhounds were made by local art college students in 1982 when the council restored the gates. The students constructed moulds from an original greyhound figure and made four new ones from glass fibre and concrete. One of the original wooden dogs is now housed in Wrexham’s museum.

Adjoining the gates is a pub called, unsurprisingly, The Four Dogs. The Four Dogs has a bit of a reputation locally, although that may be a little unfair as I’ve certainly never had any problems on the couple of occasions I’ve been in there. Allegedly, however, it is the pub of last resort for people who have been banned from all the other hostelries in town.

As we walk we reflect on how pub names often seem to tap into local history and mythology. Across the road from The Four Dogs is a pub called The Acton Park and, a mile or so away on the other side of Acton is another called The Greyhound. Nearby, along the eastern edge of Acton Park is Jeffreys Road, named in memory of the previous occupants of Acton Hall. When a new pub was built here in the early 1970s the brewery invited suggestions for what it should be called. The Whippet, The Swinging Judge, The Hanging Judge and The Scaffold were all rejected before they settled on the rather less edgy name of The Cunliffe Arms.

We turn down Box Lane along what was once the northern edge of the Acton Hall estate. This was once the main road to Chester before the new turnpike on what is now Chester Road was constructed. Supposedly the ‘box’ in Box Lane comes from the sentry box Sir Foster Cunliffe had installed to prevent travellers using ‘his’ road as a cut-through to avoid the toll charges on the turnpike.

Half way along Box Lane we come to Acton Park Primary School. Will’s daughters both attended this school. The oldest part of the school was built in 1917 by the Belgian-born diamond merchant Sir Bernard Oppenheimer. Oppenheimer bought all 224 acres of the Acton Hall estate when the Cunliffe family put it up for sale that year.

He immediately sold 64 acres to the council for what was to become the Acton Park housing estate and gifted 125 acres to a trust set up to provide small-holdings for ex-servicemen. He also built a factory unit on Box Lane on the site of the present school. His plan was to set up a diamond polishing works to provide work for disabled ex-servicemen. The initiative was not a success, however, and the site was sold to the council in the early 1920s.

We take a right down a street called Acton Gardens which leads through to Acton Park. This street edges the former kitchen garden of Acton Hall and some parts of the estate’s original sandstone walls, formerly extending for some 23 miles around its perimeter, are still evident here.

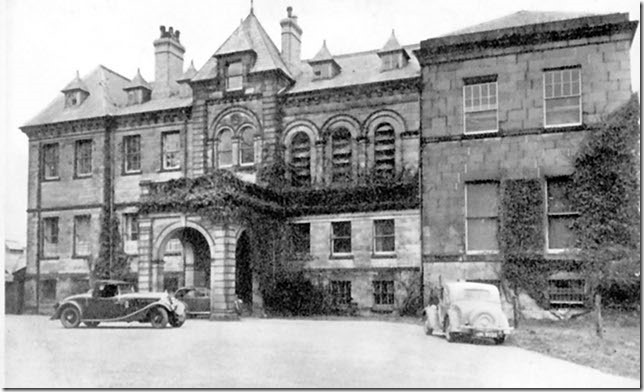

The older houses in Acton Gardens appear to date from the 1920s but, just before we enter the park, we pass through a new development of town houses around a faux-village green. There is also a large three-storey apartment block modelled, so Will tells me, on the original Acton Hall. Although, to my mind, it doesn’t seem to bear much resemblance to the any of the archive pictures I’ve seen.

Acton Hall was built by the Jeffreys family in the sixteenth-century and was the birth-place of Judge George Jeffreys. The house passed through several other hands before being sold to Sir Foster Cunliffe in 1785. He made improvements to the house, expanded the estate and made it the Cunliffe family seat for another 130 years.

But the Cunliffes were not originally from the landed gentry; Sir Foster’s grandfather, who was also called Foster, was a Liverpool merchant who amassed his fortune on the back of the slave trade, a part of their family history which later generations tended to play down.

Sir Foster, the 3rd Baronet of Acton Hall, died in 1834. The final Cunliffe family custodian of the hall was the 6th Baronet, Sir Foster H E Cunliffe, an Oxford don and MCC cricketer. He succeeded to the title in 1905 but died in the Somme in 1916.

By 1917 the Cunliffe family’s fortunes were at a low ebb and they vacated the hall and put its lands up for sale. The house itself remained unoccupied. It was used as a furniture store in the inter-war years and as a billet for the US 33rd Signals Battalion in WW2. The building’s fabric continued to deteriorate and, with no resources to restore it, the council demolished Acton Hall in 1954.

Some of the grandeur of the Acton Hall estate is still apparent to us, however, as we meander across Acton Park. The park comprises 55 acres of grass, trees and ornamental gardens. At its centre is a lake which was once Acton Hall’s fish-pond.

To the south of Acton Park we pass through Wrexham’s oldest council housing estate, also called Acton Park. The first 118 houses were built in 1920 following the ‘garden village’ concept of gardens, crescents, open-spaces and landscaping. The architect was Professor Sir Patrick Abercrombie of Liverpool University. More houses were added in subsequent decades, but they seem to lack the build-quality and imagination of Sir Patrick’s original design.

Beyond the Acton Park council estate we cross a main road and follow Park Avenue back to our starting point in Westminster Drive. Park Avenue is a wide, tree-lined road with an almost continental feel. It was originally called Cooper’s Lane but, when a number of large houses began to be built here in the 1930s, the council felt it needed a grander street name to attract the ‘right’ kind of resident. They also planted an avenue of 52 trees at the then astonishing cost of £22-16s-00d.

Sensing I might be tempted to write something wistful about Acton Hall and days gone by in Wrexham, Will reminds me before we part of the murky antecedents of the Jeffreys and Cunliffe families. Even Bernard Oppenheimer, he added, for all the good he tried to do for people disabled in the Great War, wrested his colonial diamond fortune from its rightful African owners.

But the resonances abound; so many of the street names in this part of Wrexham pay homage to the legacy of Foster, Cunliffe, Acton and Jeffreys. And that greyhound motif keeps turning up in odd places. Which just leaves me with the four dogs. After all, everyone likes dogs.

Good stuff Bobby. Some fascinating connections. Interested to hear about the Patrick Abercrombie estate as well. Also like how almost every town has a story about the pub of last resort!

Abercrombie designed the local FE college (now part of Glyndwr University) too. I think Britain’s pub culture is ripe for some psychogeographical investigation. Sounds like a fun gig!

Pingback: The Wrecking Ball | Psychogeographic Review