Swathed bodies in the long ditch; one eye upstaring. It is safe to presume, here, the king’s anger. He reigned forty years. Seasons touched and retouched the soil. Heathland, new-made watermeadow. Charlock, marsh-marigold. Crepitant oak forest where the boar furrowed black mould, his snout intimate with worms and leaves.

Geoffrey Hill, Mercian Hymns, XI.

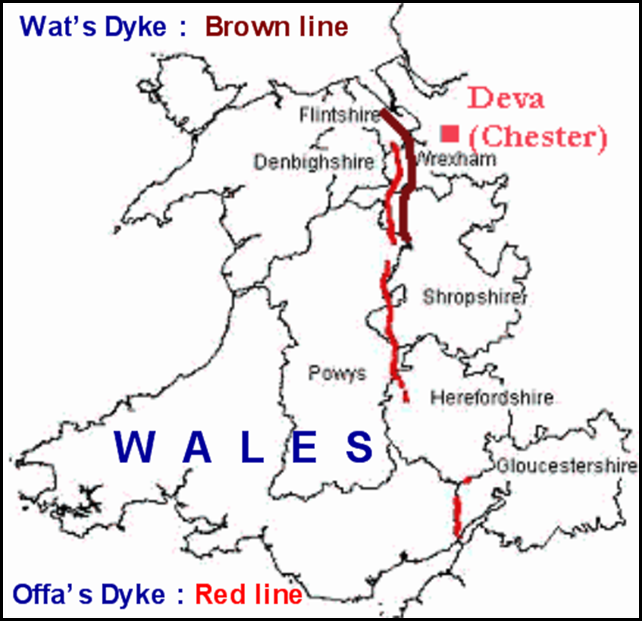

There are a couple of initial problems with writing about Wat’s Dyke. First of all, we don’t know exactly when it was built, though the best current guess is that it was completed during the ninth century, at some point before the better-known Offa’s Dyke. Secondly, we have no idea of the identity of the eponymous Wat. We can be pretty certain that the dyke was built by the Saxon kingdom of Mercia as a defensive barrier against the Welsh to the west. There is no record of a local ruler or military commander by the name of Wat so the name of the dyke may well be derived from the Anglo-Saxon word wæt, which means wet and is perhaps appropriate for this decidedly dank part of the world. But maybe this mystery about when and by whom it was built is part of the charm of Wat’s Dyke.

The dyke is about forty miles in length and runs from north Shropshire up through the present-day counties of Wrexham and Flintshire, ending near the ancient town of Holywell. This is border country, shaped and moulded by human hand over many centuries. It is not a wilderness; much of Wat’s Dyke runs through established farmland and skirts round a number of villages. Its course also takes it through the urban heart of Wrexham. And yet, in the sections where the ditch and dyke earthwork is still evident, such as in the two pictures above, something curious happens. Wat’s Dyke seems to have a character of its own; walking along the top of the dyke, one seems to feel separate from the surrounding farmland. Separate in both a physical and a temporal sense; one has a feeling of being cocooned within a timeless corridor or walkway; one where the dyke’s Saxon makers are still very close at hand.

We set off from Ruabon, just across the Welsh border from Oswestry, and head north along way-marked paths. This is one of the best preserved sections of the dyke. A 2.5 metre ditch was originally flanked by a 2 metre dyke on its eastern side, giving good visibility across the flat river valley towards the Welsh hills. But along the top of the dyke the hedgerow is dark and dense. Below, the black, still water of the ditch sits and broods. The whole place has a cold, mournful feel and we trudge on silently.

As we pass through a rusty kissing gate, a wild-haired figure on a quad-bike rears up from behind a hedge like some marauding charioteer. He stops, smiles and bids us good day. He farms this land, he tells us. The farmhouse which we’d passed earlier belongs to him and is ‘fairly new’, having been built just three hundred years ago. But his family have been on this land since the fourteenth century.

The dyke continues north through farmland and then passes through the parkland of the Erddig estate, which is now controlled by the National Trust. From here we walk through the centre of Wrexham, noting, courtesy of Pete Lewis’s excellent book, that the parish church is dedicated to St Giles, the patron saint of lepers. The town once had more than twenty breweries; I recall visiting Wrexham in the 1980s and enjoying the heady aroma of hops and malt which clung to the very fabric the town.

To the north of Wrexham the nature of the countryside changes and the mark of old industries, which have come and then gone, is more evident. We pass an abandoned quarry and spoil heap near Gresford. The village of Gresford will forever be associated with the mining disaster of 1934 when 266 men died. They were all docked a quarter day’s pay for not completing the shift.

Towards Llay a number of derelict mine-workings can be seen from our route. Grown-over and relentlessly merging back into the landscape. At one level they present an ineffably sad picture, but these works of humankind seem at least to be making their peace with nature

Towards the end of our walk, where the path skirts a road, we stop to inspect a fly-tip sculpture adorning the embankment. No trace of the dyke itself is evident for the last two or three miles of our walk. We end our journey at Caergwrle, home to a ruined thirteenth-century castle built by Dafydd ap Gruffydd and formerly a spa town. Travelling home by train, we talk about our day. What have we learned? Nothing very much about Wat and the builders of his dyke. But the whole point was the journey, the walk, not the destination. But we did return home with a real sense of an ancient border landscape and a path walked by many before us.

Paths that cross

cross again

Paths that cross

will cross againPatti Smith, Paths That Cross

Map courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Fascinating piece, Bobby.

Thanks Billy!