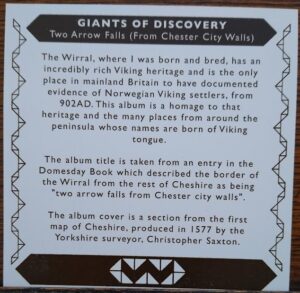

Something different for the new year. A found document from nearly twelve years ago. It’s a kind of origin myth for this blog. It should have been my first post when I started The Psychogeographic Review back in 2012. Perhaps it will be my last.

As soon as I wake up I know that she has gone. The flat is empty, silent. I make coffee, then pack my bags and call for a taxi. It is time to move on, I have an investigation to complete. There are questions in need of answers, which in turn will lead to more questions. I am not the ideal person for the task, but I can see no one else stepping forward to attempt it.

The Queen’s train arrived at Ruabon station at 4.15pm precisely. Her horse-drawn carriage, together with an escort of mounted Denbighshire Hussars, was waiting for her at the station entrance. My train pulls into the same station at just after 10.00pm over 100 years later. I step down from the carriage and make my way along the platform, a laptop bag over one shoulder and a heavy suitcase dragging along behind me on its impossibly small wheels.

In 1889 Victoria’s carriage awaited her no more than a dozen paces from where she left the train. This year the single taxi waiting outside the small station is snapped up by the elderly couple shuffling along just ahead of me. So, suitcase skittering along behind, I follow the curve of road from the station forecourt into the main street of the village. Here I find a taxi office squeezed in between a pub and a Chinese take-away.

By way of conversation the taxi driver asks why I got off the train in Ruabon, one station short of Wrexham General, if Wrexham was where I was heading. I’d have saved myself a six-mile taxi ride, he says. I know this, of course: I’d lived in the town before. But I decided on the train up from Harwich, as I read about the route of her visit, that I wanted to arrive in Wrexham by the same road Queen Victoria took all those years before. I think it best not to mention this to the driver, I always find it best to downplay my odd obsessions when I’m in company. I say instead that I haven’t been to Wrexham for a long time and I want to see a little of the area from the car. In the bloody dark, he mutters to himself.

Victoria was staying at Palé Hall, near Bala. She took the train along the Dee valley to Ruabon and from there processed to Wrexham, where there was to be a civic welcome and concert in Acton Park. Afterwards she took tea in Acton Hall, and then returned to town in her carriage, picking up the train for her onward journey at Wrexham General station this time.

Acton Hall 1829

Acton Hall is no more. My vehicle pulls up outside an apartment block in Acton Hall Walks, near to the site of the old manor house. I pay the taxi driver and he sits watching me while I struggle to the front door of the building with my luggage. I’ve been abroad for so long that I’ve forgotten the expected tipping etiquette in this country, but clearly I haven’t given him enough to warrant his helping me with my bags. I stand at the firmly locked front door wondering what to do next. I’m sure it had been agreed that someone was going to meet me here. I turn round at the sound of the taxi-cab driving off and as it do so another car arrives and parks in front of me, dazzling me with its lights.

Acton Hall Walks Apartments

A young woman in a business suit gets out and strides briskly towards me. She is brandishing a practiced smile and a bunch of keys and introduces herself as the letting agent. She leads the way up to the flat and lets me in. Second floor furnished, two bedrooms, two bathrooms and an open-plan living room/kitchen with windows overlooking the park she recites, clearly eager to be on her way. You’ve already signed all the paperwork for a six-month let, she says, so unless there’s anything else?

I have no questions, so she shakes my hand and leaves, her heels clattering down the corridor. Years of travel have accustomed me to moving on to my next abode lightly with few possessions, but it’s also given me an appreciation of simple comforts, so this flat will be more than enough for my needs. My books and papers will arrive sometime soon and I already have my laptop and notebook, so anything the flat lacks I can easily do without. I have a phone, though I never call anyone and rarely text. But it gives me access to information on the go and serves my need for a camera without the cumbersome bulk of the SLR I always used to carry.

* * *

It’s not something I’d planned, but I make a spur of the moment decision as I open the living room blinds that first morning and see the view across the park. Before me is a vista of trees, undergrowth and meadow sloping away into the middle distance; beyond this are the tops of more trees. This view of Acton Park suggests to me that one might have seen a very similar prospect from the upper windows of Acton Hall, which once stood in this spot. I reach for my phone and take a wide-angle picture of the view before me, having already decided that I will do the same every morning for the duration of my time here. The same view every morning, building up over time a record of the subtle daily changes as summer turns to autumn and then into winter. I like to work within a framework and this ever-expanding set of pictures gives me one.

* * *

I walk, I look, I write; every investigation starts in the same way. This morning I start in Acton Park, walking its perimeter and then heading down the slope towards its centre. She sits on a bench looking out over the pond. She stares at the water so intently that it is obvious that she is aware of my approach along the path that passes her bench. She is warily alert. I am used to this: people sometimes find the intensity of my presence unsettling. Mindful of this, I put my head down and walk ahead a little more swiftly, making a show of ignoring her. But as I pass she speaks. People keep on feeding the ducks with bread, she says. It’s not good for them, but they still do it. Why is that, do you think? I slow down and turn my head in her direction. She continues to stare at the water and I sense she does not actually want an answer. The birds can’t help it, she continues, eventually all that bread will kill them, but they keep on eating it. They just can’t resist.

I stop beside her bench, feeling it is only polite to wait and show that I am listening. She is still looking at the water, silent now. So much so that I start to wonder whether she was actually addressing me or simply talking to herself, or maybe the ducks, who are languidly patrolling the shallows near her, ever hopeful. It’s a beautiful morning though, I say, if only to fill the silence. Really? She says, turning to face me for the first time, her brown eyes boring into my face. Or is that just something people say? I smile, unsure how to respond.

Acton Park Pond

Next you’ll be quoting Keats on beauty, she says. So why not tell me something beautiful and possibly even true? That would be the writerly thing to do, she says, nodding towards the notebook cupped in my right hand, a momentary flicker of a smile in her eyes. Ah yes, I say, still struggling for a response. My name is Bennett, she says, I guess I’ll see you around. And with that she turns back to face the pond. Taking that as my signal that the conversation is over, I mumble a goodbye and continue on my way.

Later, back at the flat, I settle down at the kitchen table to write up my report. I fire up my laptop and open up a file I’ve already labelled The Psychogeographic Review. A buzzing sound breaks my reverie. What’s that? An alarm of some sort, or perhaps a timer? Then I realise it is the phone on the wall by the front door. I recall now being shown that last night: it is the intercom linked to the outside door.

Removals, the voice says, we’re here with your stuff. I press the button to open the front entrance then prop open the flat door with a heavy chopping board. Two men in matching green polo shirts bustle in, each pushing a sack truck bearing two tea-chest sized boxes. I direct them to stack the boxes against one wall of the living room. One more journey from the van and they are done. Seven boxes: all my worldly possessions, a jumble of mainly books, papers and clothes. I’m not sure what else is inside; I never fully unpack these boxes from one home to the next, I just reach inside if there’s something I need. Why bother unpacking, only to have to pack again?

I turn my back on the boxes, feeling weary with the very idea of them. I take two steps and sit at the table. I have my journal to write up and I want compose my report while it is still fresh in my mind.

* * *

All paths lead to the pond, or so it seems. I follow the curve of gravel along the water’s edge and see her across the pond from a distance. She sits on the same bench. Somehow I knew she would be there. Once again she seems to be acutely aware of my approach, but deliberately continues to look the other way, eyes fixed on the murky waters of the pond. If she doesn’t speak. I will just keep on walking, I tell myself. It’s not as if we’ve arranged to meet.

Hello Mr Writer, she says as I near the back of her bench. Hi, I answer, it’s cloudier today. She turns and we share a brief awkward smile at the banality of my remark. Going somewhere? I say, with a nod towards the well-stuffed rucksack on the bench beside her. Maybe, she says, what do you think? I really don’t know, I say. She stands up, slides the straps of her bag over her narrow shoulders and walks around the bench to join me on the path. Shall we go? she says.

As we walk, Bennett points out the stone circle squatting on an area of flat ground just beyond the lake. Not Neolithic, of course, she says. A modern reproduction for the National Eisteddfod in 1912. You know, the crowning of the bard and all that? There’s something both tragic and inspiring about a nation that celebrates poets as national heroes, don’t you think? And not dead poets, she continues, but new ones. OK, so they’re required to write in the straight-jacket of an ancient metre, but they’re still living poets. Even the occasional female one too.

As we pass the circle Bennett says: You see that other stone over there, the one standing on its own? I nod. It’s more of a post than a Gorsedd stone, of course. Well, legend has it that George Jeffreys, the Hanging Judge, used to tie his horse to it when he wanted to stop to admire the view across the Acton estate. His family owned the house and all the land around her, you know that?

She stops and turns to face me, eyes fixed on mine and hands balled into fists. If you stand by the stone at midnight, so the story goes, turn around three times saying his name with each turn, then Jeffreys will appear before you. She’s holds her gaze on me for several seconds, without blinking, then softens her face into a broad grin. Absolute fucking nonsense, of course! And I should know, believe me.

It strikes me that I have no idea who Bennett is, nor where she comes from. Neither do I know where we are walking to together. My mind’s eye swoops up above us and I see the park with its lake and, nearby, the stone circle with the two of us walking just beyond it. At the top of the slope I see the modern recreation of Acton Hall, my temporary home. I know now, it feels as if I’ve always known, that this is where we are heading. It’s as if there is something that Bennett and I share, but I can’t for the life of me work out what it is.

You live locally? I ask. Not really, she answers. I move around a lot. She nods to herself, as if satisfied with her explanation. We pass a section of ancient wall that forms an entrance into the park. You’re moving on somewhere now then? I mean, I say to her, you have your rucksack with you. I already know the answer.

We are out amongst the new houses of Acton Hall Walks now, heading for the apartment block. Just a few nights then, she says. Thanks for offering. Bedding down on the sofa will suit me fine. And so it was settled. Though I had made no such offer, it seemed too unbearably awkward to try to contradict her now. The flat had a spare room, but Bennett turned it down and insisted she was happy to sleep on the sofa. Which was fine, but for the fact that the flat’s entire open-plan living area had now become her domain. Still, it was good to have someone to work with on my investigation; to join me on my walks.

* * *

I think the idea’s fascinating, says Bennett. We are sitting at the dining table in the flat and planning the next day’s walk. What you’ve got, she continues, is one small town divided into two: Wrexham Abbot and Wrexham Regis. One half is owned by the church and the other owes allegiance to the crown. The two rival entities of hereditary power: church and crown fought over this town. They reached an impasse and tacitly agreed to divide it between themselves. Wrexham Abbot and Wrexham Regis: Janus-faced, impassively cruel.

But it’s not unusual; it’s a story, a history, that plays out all over England and Wales. She taps the table between us to emphasise her point. Have you read any Tudor history? You need to remember there was a civil war in this country a century before Parliament and Cromwell began to flex their muscles. What I’m talking about is Henry’s war against the church, and it wasn’t confined to armies on battlefields, but it took place locally in each town, village and country estate up and down the land: a real civil war. She turns to me, her eyes flaring. And, believe me, it’s still being fought.

* * *

We sit at opposite ends of the sofa. Bennett spends the evening listening to podcasts on her phone, which precludes any conversation. That’s fine by me, I need to study several local maps, tracing the course of urban rivers and streams. Rivers, especially hidden ones, fascinate me. If you follow the course of a country’s rivers and you can map out the growth of its settlements, its agriculture, its trade route and the development of its industry. That’s why I want to have a look at Wrexham’s two rivers, the Gwenfro and the Clywedog. As soon as I start marking the map with a highlighter pen I can tell that I’ve caught Bennett’s attention. I look across at her and, as soon as I catch her eye, she takes out the ear buds and looks at me.

What are you up to? I tell her my ideas about the Wrexham’s urban rivers and how I’d like to explore them. We can do that, she says, but you’ll not find a lot of the Gwenfro, the section through the centre of town particularly, it’s been built over. It’s not exactly a lost river, but it’s hard to follow its exact course. But even when its underground, the clues are all there, if you know what you’re looking for.

OK, I say. I really want to get to the confluence of the two rivers. According to the OS map, it’s at King’s Mills. Bennett leans on my shoulder and studies the map. Her breath brushes my cheek. We’ll start here, she says, stabbing a finger at a short thread of blue in the town centre.

* * *

No, it’s not travel writing, I explain to Bennett; not that kind of thing at all. What I’m trying to do is investigate the personality of the town. She looks at me in that silent, unblinking way she has. I try to ignore the discomfort this causes me and continue to speak. Places have personalities, don’t you think? Her face is impassive but her eyes are alert, watching. All those people who have lived in a place, I continue. All those lives, generation after generation, they leave a mark. The things they’ve done, and said, and thought, they all have a resonance, something etched into the very fabric of a place. Just go to Auschwitz, or Culloden or the area around where Newgate stood in London and you’ll feel it; there’s something palpable in places like that.

Something evil? she asks. Yes, I answer, but not just evil. There’s sadness, joy, spiritual benevolence…. everything. Places have the endless variety of individual characteristics that people do. So are you ready for what you’ll find with this investigation of yours? she asks. What do you mean? I say.

Bryn Estyn

She leans forward to emphasise her words. I mean there’s a lot of darkness in this town. She frowns. It’s an oppressive darkness. Acton Hall was built on the proceeds of the slave trade. Elihu Yale, he’s given pride of place with a memorial in the parish church and a sixth form college is named after him, he was another slave trader. Bryn Estyn children’s home, you’ve heard of it? It was at the centre of a massive child sex abuse scandal over many years that was finally exposed in the nineties. It’s now a council staff training centre. But there’s something dark, corrupting and corroding there still. A malign influence. He stalks the corridors of Bryn Estyn. The victims, those who didn’t die young, survived and grew into men. Torn flesh will heal and bodies will recover. But the person inside that body is broken forever, indelibly scarred.

Gresford Colliery

Then there’s Gresford Colliery, 266 men and boys buried underground because corners were cut on health and safety in the name of profit. A lot of the colliers who died that morning in 1934 had switched their shift so they would be free in the afternoon to watch the big football match, Wrexham against Tranmere Rovers. The club still holds a minute’s silence before the home game on the nearest date to the anniversary each year. So much darkness. She shakes her head and slumps back into the sofa.

* * *

We sit in silence for several minutes, then Bennett raises her head and speaks again. Acton Hall is gone. It was burnt down and demolished in the 1950s. But how much of its influence lives on? It’s like a malign resonance seeping into the very soil of this town. This apartment block: a brick and render edifice raised up in the image of a building that was meant to have been destroyed. It’s been built on the cursed site of the original, which in turn was built on the crushed bodies of people torn away from one continent and taken to another. Blood money, the proceeds of the slave trade.

Did you know that African-American soldiers were housed in the Hall during World War Two? Yeah, young men wearing the uniform of the nation that oppressed them at home and which continued to do so here, 3,000 miles away and in the teeth of a European war. Even while they were here America still segregated them from other young men wearing the same uniform but who happened to have skin of a different colour.

Before that there was the Belgian-born diamond merchant Sir Bernard Oppenheimer who bought 224 acres of the Acton Hall estate when the Cunliffe family put it up for sale in 1917. He immediately sold some of the land for housing and set up workshops and small holdings on the remaining plot. He claimed he was trying to do something positive: helping disabled ex-servicemen to rebuild their shattered lives; teaching them new skills, giving them jobs. Diamond polishing, says Bennett, her lip curling in distaste as she utters the phrase. Gems taken from their rightful owners in Africa. Even worse, they made those owners dig them out of the ground, paying a pittance and working them death in many instances. Blood diamonds. How is that any different to slavery?

* * *

I sit at the table with my papers and maps the next morning. My task, I am convinced, is to establish the underlying pattern, the links between all of these nodes. There seems to be a duality, a similar pattern in the two adjoining towns of Wrexham and Chester. I can almost feel it; it squeezes at my head. It’s as if there is retaining band enclosing each town’s core and ganglions of energy stretching out into the surrounding area and linking the two centres. In the case of Wrexham the outer circumference seems to be the area within the boundary of the ancient twin boroughs of Wrexham Abbott and Wrexham Regis. For Chester the enclosing circle is demarcated by the line of the Roman wall, which in turn was built on a much older perimeter.

What is the link between the two centres? Look at the map and you see Wrexham and Chester straddling the ancient border between Wales and England. Just ten miles apart, but forever united and always divided. Is the road the link? Not the modern A483, but the older road that is Watling Street. This route skirts Wrexham to the north-east of the town centre, crosses the Dee at the site of the old ford at Aldford and then runs through the centre of Chester towards York. So it’s possible that Watling Street is the link. Indeed, it follows the route of a much older path that linked the two towns generations before the arrival of the Romans.

I look closely at the map again and it’s obvious what the link is: the river. Before we had passable roads people would travel and trade along the river routes, in this case the River Dee, a permanent umbilical cord linking north-east Wales and Chester and, beyond Chester, the sea.

* * *

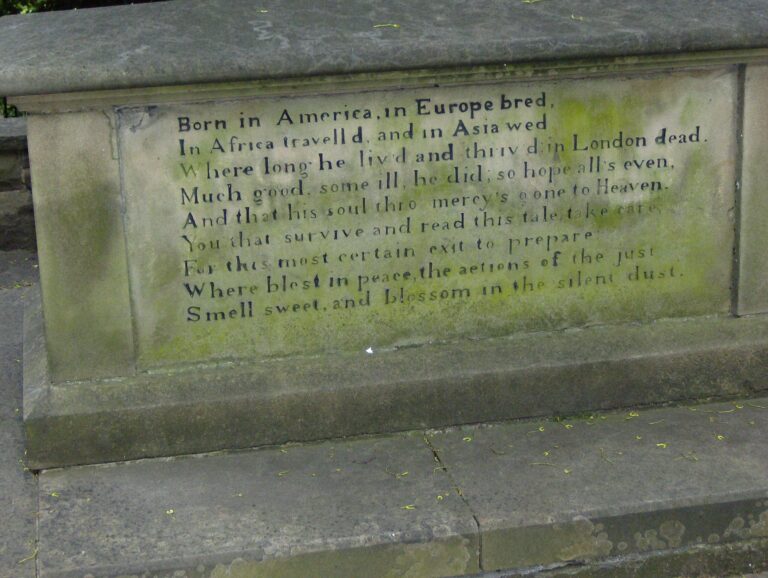

Sinclair Grave, Gresford

I sleep late the following day, lying there until almost lunchtime. I knew I was doing it; part of me was awake and aware that my inert body was lying there and I listened to my own slumbering breath. Bennett says she’d been out for a walk while I was asleep. I took the footbridge over the dual carriageway, she says. Then I followed the lanes all the way to Gresford. You remember that pond in the centre of the village? I nodded. Well, she continued, I saw May Sinclair there. Not dead. I knew it was her. It was so fucking obvious really. I followed her all the way to the churchyard. She stood by her brother’s grave for a minute or two and then hurried off. Mother will want to know why I’ve been away so long, I heard her say.

* * *

The lights flicker as I leave the apartment and walk down the staircase. My vision swims in and out of focus. The hard steps become softer. I don’t remember them being wooden. A runner of carpet winds up the middle. Creaking steps. A smell of log fires, furniture wax and tobacco smoke, A large hallway, dimly lit, doors leading off. I stand and wait. A clock ticks. Loudly. Is it my imagination, or is it getting louder by the second. A door opens and a maid, dressed in black and white, walks silently into the hall with a tray. She glances at me and then, eyes downcast, says: shall I take this up to your room, sir? Or will you take your brandy in the library?

* * *

Moments later, or perhaps decades, I step down into the hallway. I am aware of khaki uniforms, neatly pressed. The two African-American soldiers stride in step past me, one on either side. I feel a movement in the air, smell leather and boot polish, but neither of them acknowledges my presence, nor even seems to notice it. Nothing is where it should be. I open a door on the ground floor and enter a room. Heavy oak furniture and a Persian rug, a fire blazing in the grate.

So why was this apartment block built in the image of Acton Hall? And not just that, but actually placed on the footprint of the old building. There’s an essence of Acton Hall that remains, a vestige that couldn’t be destroyed by their fire and bulldozers, something stronger than mere stone and brick. And this building celebrates it. What’s more, it flaunts it.

* * *

There’s a negative energy here. I don’t know where it comes from, but it’s here. It’s in the soil, the rock, the streams and rivers. May Sinclair sensed it, which is why she moved away; but not before two of her brothers died and her mother went mad. Look at Bryn Estyn and everything that went on there: the cruelty, the perverted desire and the young lives destroyed. Continuing the twisted rites of George Jeffreys and Elihu Yale; lynching, squeezing the life out of young bodies in the name of God and the law. Their law. There is a darkness her, can’t you feel it?

Then, I asked her, why do you stay? Maybe it’s for the same reason you’re here, she replied. This investigation of yours, what do you hope to uncover? It’s not as if everything is hidden, it’s all out there in the open for those who choose to see it. But most people do not; it’s too uncomfortable, too disturbing, so they convince themselves they can’t see it and let it remain under the surface. These things, these dark connections, become a series of obscure footnotes and are never linked and rarely traced back to their source.

* * *

Acton Hall Interior

I step out of the door of the flat again. Even before my eyes can focus, my feet tell me something is different. In place of the familiar ringing hardness of polished concrete in the corridor, I sense something softer beneath my feet; the springy feel of carpet and wooden floorboards is unmistakable. As my eyes adjust to the dimness of the corridor, I realise that the only light was coming from an oil lamp on a small table pushed against the wall further down the passage to my right. I take a deep breath; the air is cool and smells of furniture polish and burning coal. I walk towards the lamp and, in its arc of light, see that the corridor turns to the left. I follow the turn and ahead of me see a staircase leading downwards.

Though I walk softly, hesitantly, the stairs creak with each step. At the foot of the stair-case I reach a large room lit by several lamps. A fire blazes in the grate of a stone fireplace and casts dancing shadows across the high ceiling above me. Before the fire are two armchairs, Someone, I suddenly realise is sitting in one of them. I stop walking and all but stop breathing. The figure in the chair holds a book on his lap. He looks up, turns his head and stares straight at me.

* * *

The next morning, as soon as I wake up I sense that Bennett has gone. I wander through the empty flat looking for any sign of her presence, any reminder of her absence. Her bag has gone and she has left no message behind. I do not need a note to tell me that I will never see her again.

Like this:

Like Loading...

Adam Scovell is a writer and filmmaker from Merseyside, now living in London. He completed his PhD in Music at Goldsmiths University in 2018, and now writes regularly for the BBC, the BFI and many other outlets. He is the author of Folk Horror: Hours Dreadful and Things Strange (2017, Auteur), alongside three novels all published by Influx Press.

Adam Scovell is a writer and filmmaker from Merseyside, now living in London. He completed his PhD in Music at Goldsmiths University in 2018, and now writes regularly for the BBC, the BFI and many other outlets. He is the author of Folk Horror: Hours Dreadful and Things Strange (2017, Auteur), alongside three novels all published by Influx Press.

Final Approach is the story of Blackburn’s life, with the constant thread of his love of planespotting running through it. He charts this obsession from his childhood right through to the present day and describes his compulsion to see planes, photograph them and note their registration numbers. Indeed, planespotting determines the whole structure of this, his autobiography. Each chapter heading is the three-letter IATA code for an airport (MIA, LGW, ORK and so on) and each airport plays a significant part in the story of Blackburn’s life.

Final Approach is the story of Blackburn’s life, with the constant thread of his love of planespotting running through it. He charts this obsession from his childhood right through to the present day and describes his compulsion to see planes, photograph them and note their registration numbers. Indeed, planespotting determines the whole structure of this, his autobiography. Each chapter heading is the three-letter IATA code for an airport (MIA, LGW, ORK and so on) and each airport plays a significant part in the story of Blackburn’s life. Just over ten years ago the Dorset-based publisher,

Just over ten years ago the Dorset-based publisher,  Ghost of an Idea examines the impact of nostalgia on the horror and hauntological genres. In this deeply researched work William Burns addresses the question of nostalgia, which can be defined as a longing for a past that may once or may never have existed. Is it, he asks, a force which stimulates contemporary creativity, encouraging further exploration and expression? Or does nostalgia too often produce a culture that is a bland shadow of the original upon which it is based?

Ghost of an Idea examines the impact of nostalgia on the horror and hauntological genres. In this deeply researched work William Burns addresses the question of nostalgia, which can be defined as a longing for a past that may once or may never have existed. Is it, he asks, a force which stimulates contemporary creativity, encouraging further exploration and expression? Or does nostalgia too often produce a culture that is a bland shadow of the original upon which it is based?

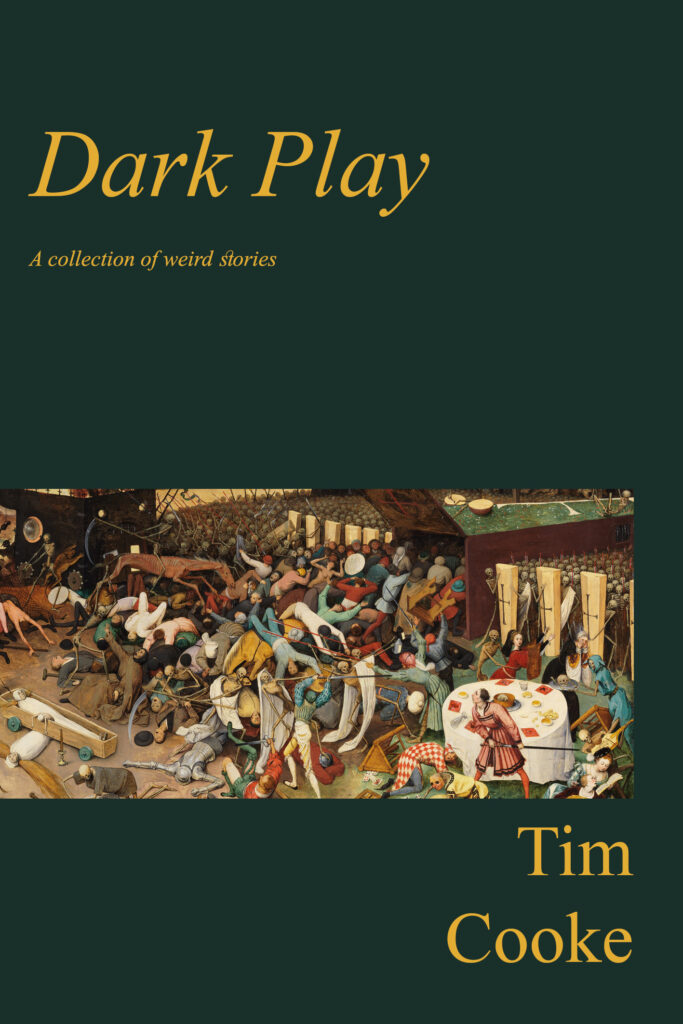

Tim Cooke is a teacher, writer and creative writing PhD student. He was the winner of the New Welsh Writing Awards 2022: Rheidol Prize for Prose with a Welsh Theme or Setting for his blended nonfiction book, River.

Tim Cooke is a teacher, writer and creative writing PhD student. He was the winner of the New Welsh Writing Awards 2022: Rheidol Prize for Prose with a Welsh Theme or Setting for his blended nonfiction book, River.

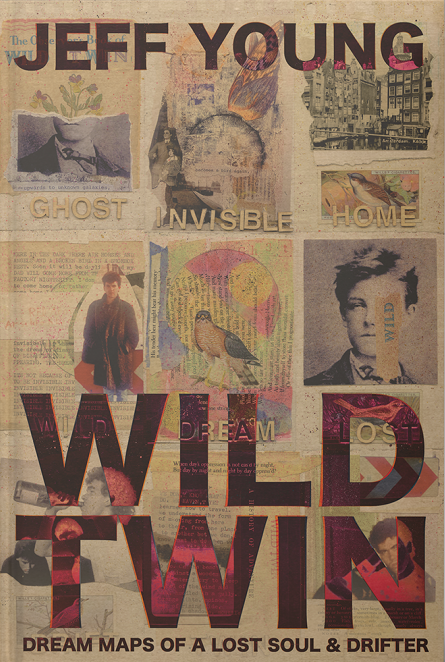

Jeff Young is a writer for screen, stage and radio. A former senior lecturer in Creative Writing at Liverpool John Moores University, Jeff lives in Liverpool. He is also the author of Ghost Town.

Jeff Young is a writer for screen, stage and radio. A former senior lecturer in Creative Writing at Liverpool John Moores University, Jeff lives in Liverpool. He is also the author of Ghost Town.