Book Review – April 2022

She knew now what had happened to her. She was afraid of Harding Powell; and it was her fear that had cried to her to go, to get away from him. The awful thing was that she knew she could not get away from him. She had only to close her eyes and she would find the visible image of him hanging before her on the wall of darkness.

Mary Amelia St. Clair, better known as May Sinclair, was one of the key figures in early modernist writing. She is known for works such as The Divine Fire and Life and Death of Harriett Frean and, in the early years of the twentieth century, had a reputation as prominent as that of Virginia Woolf. She was also a respected reviewer and wrote extensively on philosophy. By the mid-century, however, she fell out of fashion, only to be discovered and celebrated once more by the feminist movement in the 1970s.

Sinclair was born in Liverpool and spent much of her creative life at the centre of literary society in London. But for several years when she was a young woman, she lived in the village of Gresford, near Wrexham in North Wales.

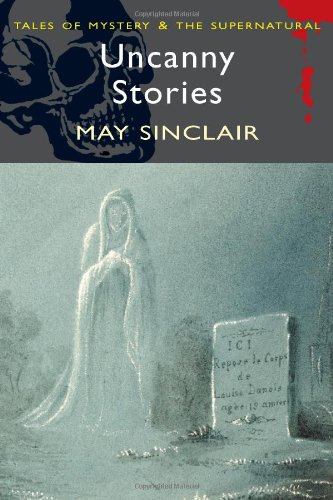

Uncanny Stories is one of May Sinclair’s lesser known works but, as a collection of odd and supernatural tales, I would put it on a par with the ghost stories of Edith Wharton and M.R. James. Indeed, for her psychological insights, I would place Sinclair’s stories on a level of sophistication above the work of the other two writers.

Uncanny Stories is a collection of eight tales covering the themes of death, belief, the afterlife, possession and haunting. Life in the world Sinclair evokes is uncertain and terrible things happen without warning. This is a world where the carefully laid plans of her protagonists do not work out as they had expected.

Both love and malice are capable of reaching beyond the veil of death. In Where their Fire is not Quenched two former lovers, now dead, are doomed to repeat the details of their affair for all eternity. While in The Intercessor a child is abandoned by her mother and carries her longing for reunion beyond the grave and stretches the boundaries of hope into obsession. Later reviewers saw the roots of this theme, which was repeated in other stories, in Sinclair’s emotional estrangement from her own mother. The truth is more complex, but many of the themes she explores in Uncanny Stories can, indeed, be traced back to Sinclair’s earlier life, and in particular her time in Gresford.

May Sinclair spent her early years in Rock Ferry on the banks of the Mersey. Her childhood was blighted by her father’s bankruptcy and his subsequent alcoholism and early death. The family moved to Ilford and Sinclair gained a place at Cheltenham Ladies’ College where her quick mind was noted and her academic rigour was developed. They then moved to Gresford and, as money was tight, Sinclair had to leave college. She and her mother were constantly at loggerheads and the younger woman, who was in the process of questioning her Christian upbringing, railed against the version of faith espoused by her mother, whom she referred to as ‘an unimaginative and inflexible woman’ who created a ‘cold, bitter, narrow tyranny’ in their family home.

May Sinclair’s time in Gresford was a traumatic and deeply formative period in her life. Her brother Harold died in 1887 and another brother, Frank, died two years later. Both succumbed to a congenital heart defect and are buried in Gresford churchyard. The trauma of these deaths is, perhaps, reflected in the story The Token in which the young wife Cicely Dunbar dies of heart failure.

May lost her faith at this time and became opposed to all forms of religious and political dogmatism and frequently spoke out against the oppressive nature of Victorian patriarchy. In his introduction to Uncanny Stories, Paul March-Russell refers to Sinclair’s dread of ‘the horrors of family life’. By the time these stories were written Sinclair had already developed an interest in the new science of psychology, as well as a fascination with the paranormal.

Although she will no doubt have read more traditional ghost stories, Sinclair’s writing in this collection is clearly more influenced by the style of psychological hauntings explored in works such as The Turn of the Screw by Henry James. Uncanny Stories displays an awareness of the conventions of Gothic horror which is reflected in the narrative structure of several of the tales, most notably The Flaw in the Crystal and The Nature of the Evidence. But Sinclair’s key contribution to the development of the ghost story comes from her use of modernist tropes and structural experimentation that are both clearly evident in this collection.

May Sinclair

May Sinclair was born in Liverpool in 1863 and died in 1946. She was a novelist, poet, philosopher, translator, and critic. She was both popular and extremely prolific, writing twenty-three novels, thirty-nine short stories, and several poetry collections throughout the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. As a critic she promoted the work of Ezra Pound and the Imagist poets, and the novelist Dorothy Richardson, among others. She also wrote works of philosophy, and was actively involved in the key issues of her day: writing pamphlets for the suffrage movement, studying and propagating psycho-analytic thought, reviewing and responding to the birth of modernism, Vorticism and imagism.

May Sinclair was born in Liverpool in 1863 and died in 1946. She was a novelist, poet, philosopher, translator, and critic. She was both popular and extremely prolific, writing twenty-three novels, thirty-nine short stories, and several poetry collections throughout the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. As a critic she promoted the work of Ezra Pound and the Imagist poets, and the novelist Dorothy Richardson, among others. She also wrote works of philosophy, and was actively involved in the key issues of her day: writing pamphlets for the suffrage movement, studying and propagating psycho-analytic thought, reviewing and responding to the birth of modernism, Vorticism and imagism.

Acknowledgements

Opening Quote is from May Sinclair’s story The Flaw in the Crystal

May Sinclair biography is by Rebecca Bowler

Gresford pictures by Bobby Seal

I’ve read H. Frean, and hadn’t realised she wrote stories in this genre – interesting.

It’s definitely worth seeking out this collection, Simon. I read somewhere that The Yellow Wallpaper was on influence on her too.