James Thomson was a Scottish-born poet, atheist and anarchist. He struggled with depression, insomnia and alcohol-abuse throughout his short life and his work frequently reflected the bleakness and despair of his life’s experiences. Thomson wrote The Doom of the City in 1857 and his best known poem, The City of Dreadful Night in 1874.

Raymond Williams calls The City of Dreadful Night: ‘a symbolic vision of the city as a condition of human life’. Williams asserts that, by the Victorian-era, the city had become a new form of human consciousness. The city of Thomson’s poem is clearly an imagined London. But it is not the dynamic hub of Empire of the popular imagination: for him it is a city of death in life. A place permeated by loss of belief, loss of purpose and loss of hope.

The City is of Night, but not of but not of Sleep;

There sweet sleep is not for the weary brain;

The pitiless hours like years and ages creep,

A night seems termless hell. This dreadful strain

Of thought and consciousness which never ceases,

Or which some moments’ stupor but increases,

This, worse than woe, makes wretches there insane.

The City of Dreadful Night takes the form of the poet’s journey through one night in the city and suggests a reworking of Dante’s Inferno. In terms of atmosphere it can be viewed as part of the Gothic tradition, but the setting is a supposedly modern city. The poem’s structure is interesting – it alternates odd-numbered seven-line sections giving description with even-numbered six-line sections giving narrative. This very mechanical structure seems to suggest an inhuman, mechanical world. A world where its inhabitants merely follow their allocated roles within a continually-running machine:

They are most rational and yet insane:

And outward madness not to be controlled;

A perfect reason in the central brain,

Which has no power, but sitteth wan and cold,

And sees the madness, and foresees as plainly

The ruin in its path, and trieth vainly

To cheat itself refusing to behold.

Thomson’s narrator is an alienated wanderer, a joyless flâneur. As he walks he encounters other aimless wanderers, in fact the city teems with people: it is a haunted space. But the wanderers walk, not to arrive, not to satisfy any purpose, but to make a kind of penance to the silent, impersonal ‘necessity supreme’ that permeates the entire city:

There is no God; no fiend with names divine

Made us and tortures us; if we must pine,

It is to satiate no Being’s gall.

In Thomson’s eyes the hopes and everyday concerns of the inhabitants of the ‘real’ London are just daydreams; eventually they will awake from what they think is reality and embrace ‘this real night’. In Masao Miyoshi’s words: ‘the desolation of the decomposing self permeates the dreadful night of his vision’.

For the poet wandering the city streets there is no alternative vision and no contrast to the unremitting gloom, as a result of which there is a complete absence of any hope. Even in that other nightmare vision of the modern city, Eliot’s The Waste Land, there is the hint of some hope, but here there is none.

Wherever men are gathered, all the air

Is charged with human feeling, human thought;

Each shout and cry and laugh, each curse and prayer,

Are into its vibrations surely wrought;

Unspoken passion, wordless meditation,

Are breathed into it with our respiration

It is with our life fraught and overfraught.

So that no man there breathes earth’s simple breath,

As if alone on mountains or wide seas;

But nourishes warm life or hastens death

With joys and sorrows, health and foul disease,

Wisdom and folly, good and evil labours,

Incessant of his multitudinous neighbours;

He in his turn affecting all of these.

Strange, dark images fill the lines of Thomson’s poem, a vision almost modernist in its self-conscious power and summoning up images of a type echoed many years later in Eliot’s work:

That City’s atmosphere is dark and dense,

Although not many exiles wander there,

With many a potent evil influence,

Each adding poison to the poisoned air;

Infections of unutterable sadness,

Infections of incalculable madness,

Infections of incurable despair.

Thomson, in his The City of Dreadful Night, characterises the city as a place of loneliness, alienation and spiritual despair for the many, which contrasts with the political and economic confidence enjoyed by the few. London in the nineteenth-century had seen an explosion in the size of its population and a proliferation of its downtrodden underclass. George Gissing wrote about the psychogeography of this human underbelly of the city in his The Nether World:

Pass by in the night, and strain imagination to picture the weltering mass of human weariness, of bestiality, of unmerited dolour, of hopeless hope, of crushed surrender, tumbled together within those forbidding walls.

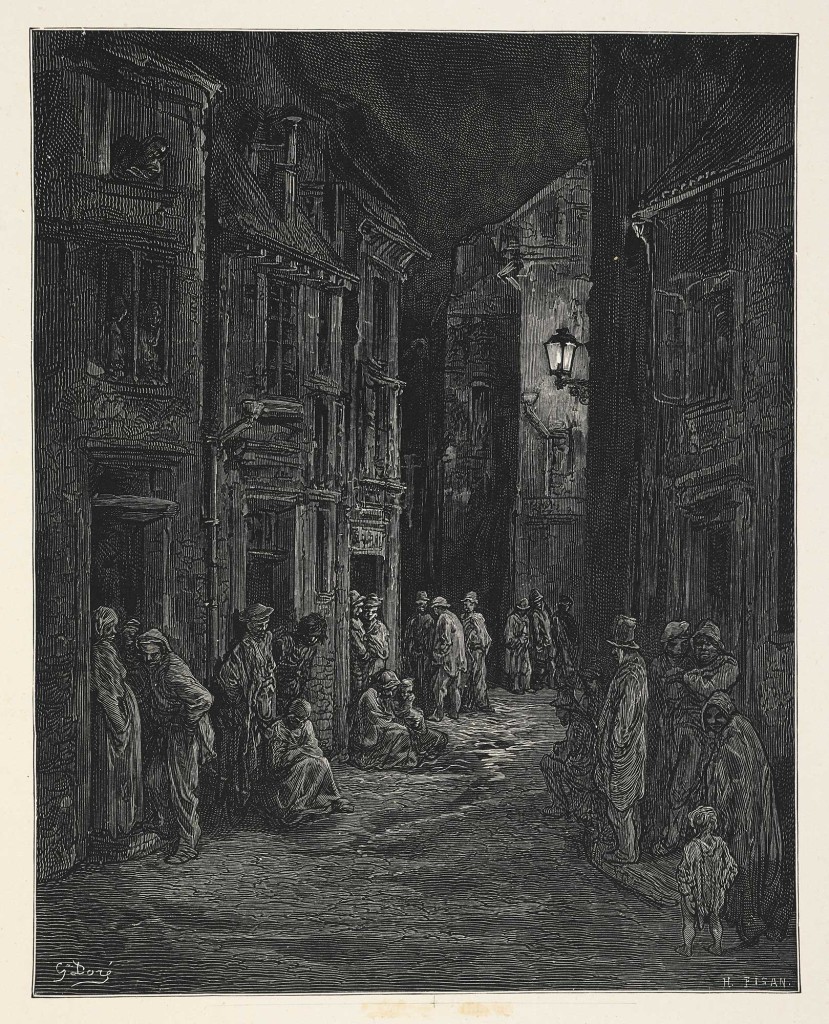

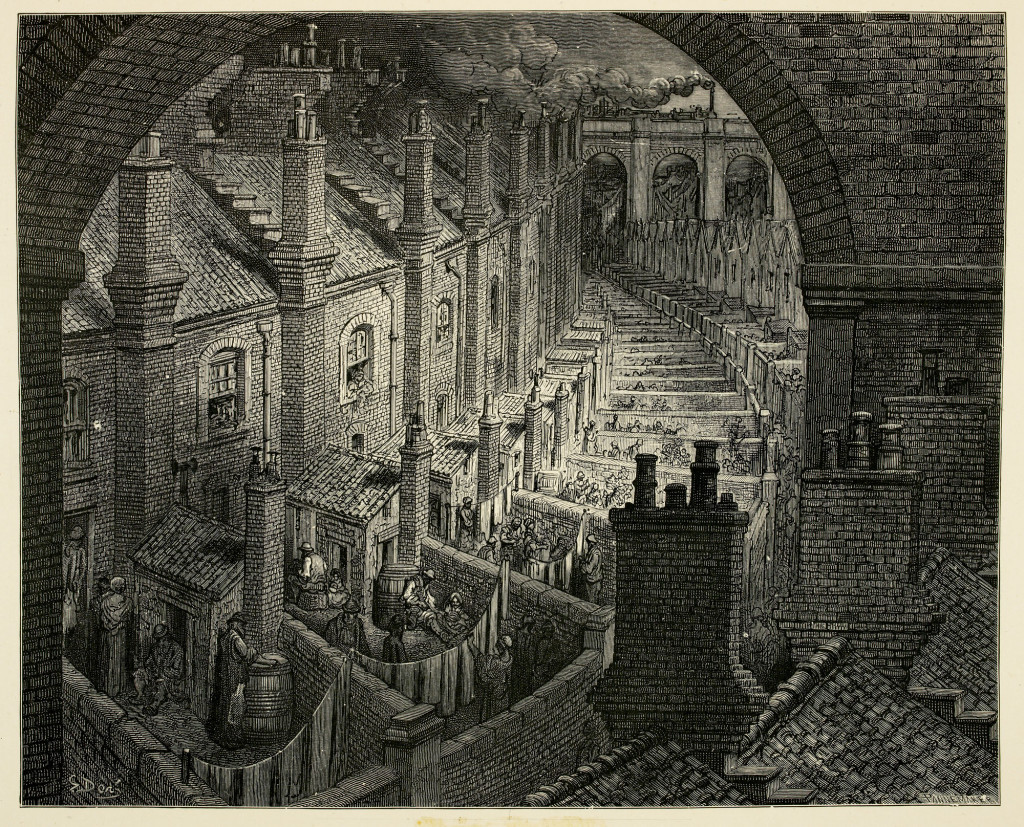

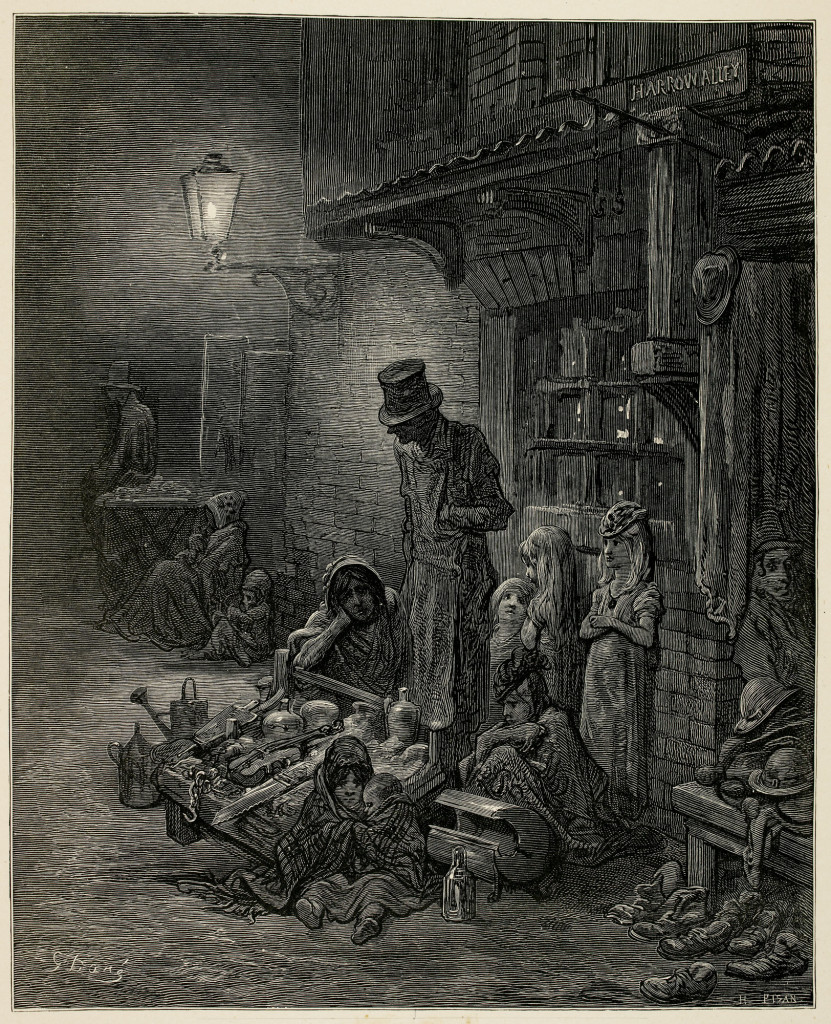

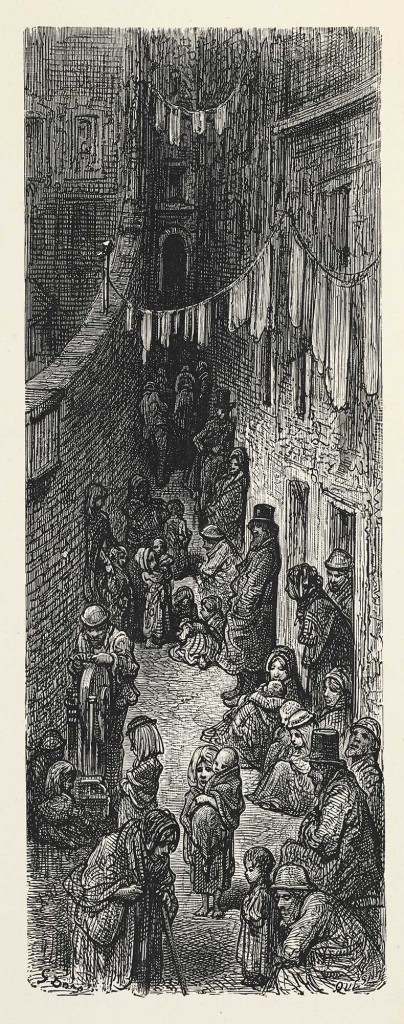

The French artist Gustave Doré, together with his journalist colleague Blanchard Jerrold, spent three months wandering the grittier streets of London in 1872, just before The City of Dreadful Night was published. As a result of their investigations they published London, A Pilgrimage to highlight the experience of London’s poor, or what Jerrold called ‘that long disease, their life’. Doré and Thomson never collaborated, but the artist’s illustrations make a fitting accompaniment to Thomson’s poem.

James Thomson, The City of Dreadful Night (1874)

Gustave Doré and Blanchard Jerrold, London, A Pilgrimage (1872)

Raymond Williams, The Country and the City (1973)

Masao Miyoshi, The Divided Self (1969)

George Gissing, The Nether World (1889)

Jane Desmarais, Review of James Thomson, City of Dreadful Night, Literary London: Interdisciplinary Studies in the Representation of London, Volume 2 Number 1 (March 2004)

Sally Ledger and Scott McCracken (Eds.) Cultural Politics at the Fin de Siecle (1995)

All Gustave Doré images used in this piece are now in the public domain.

Pingback: The City of Dreadful Night – words, words, words