Those who travel to mountain-tops are half in love with themselves, and half in love with oblivion.

Robert Macfarlane, Mountains of the Mind: A History of a Fascination

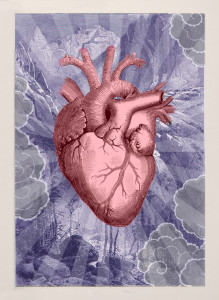

A few years ago, just after the birth of my youngest daughter, I developed a fault with my heart’s rhythm; its beat was rapid and irregular. The doctors could find no obvious cause for my condition, but the illness left me physically incapacitated to the extent where I was breathless after walking just a short distance. As someone who’d always been very active, I found this extremely frustrating and became quite depressed.

A couple of months later the medication I’d been prescribed seemed to kick in and my heart returned to its normal rhythm. Now, apart from the occasional short episode and the need to take tablets each day, I’m fully recovered. But, while I was ill I worried about what lay before me: how I would work, how I would care for my family and how I would do all the things I liked to do, like travel and walking.

I worried, but my mind also began to work, very gradually, towards a kind of resolution; a willingness to embrace a new, albeit more restricted, lifestyle. But one thing for me was emblematic of the kind of activity I might never be able to take part in again; I felt desperately sad that I might never again experience the pleasure of walking up a mountain and standing on its peak.

What is it about mountain-tops? Why do they exercise such a hold on the human imagination? In Greek mythology Mount Olympus was the home of the Gods, with the thrones of Zeus and the eleven other deities located in a temple high in the clouds. Mountains also played an important part in the beginnings of the Judeo-Christian religions: Moses received the Ten Commandments on the summit of Mount Sinai and, in the New Testament gospels, Jesus experienced his transfiguration on a mountain-top.

More recently poets, thinkers, artists, writers and composers, from the Romantics to the Beats, have eulogised the mind-expanding possibilities of wandering among the hills. In The Dharma Bums Jack Kerouac describes an ascent in the Sierra Nevada and asks: “Who can leap the world’s ties and sit with me among white clouds?” Robert Macfarlane, in his Mountains of the Mind: A History of a Fascination, posits mountains as the only wilderness landscape most of us will ever have the chance of experiencing. When we walk upon a mountain, he suggests, we are forcefully reminded that the world is far more than just a human construct.

Mountains have an undeniable physicality about them; in pushing ourselves to reach a summit we experience an altered state of consciousness in both our mind and our body. As the American poet Gary Snyder puts it: “That’s the way to see the world, in our own bodies.”

This is a short extract from a longer piece by Bobby Seal published in S T E P Z: A Psychogeography and Urban Aesthetics Zine. STEPZ is edited by Tina Richardson and the pilot edition contains a heady melange of essays, fiction, reviews, maps and images. It is available for free download here and for hard-copy purchase here.

This is a short extract from a longer piece by Bobby Seal published in S T E P Z: A Psychogeography and Urban Aesthetics Zine. STEPZ is edited by Tina Richardson and the pilot edition contains a heady melange of essays, fiction, reviews, maps and images. It is available for free download here and for hard-copy purchase here.

The drawing accompanying this piece is by Ian Long. Check out more of Ian’s work here.

A good, thoughtful piece. There is certainly a special feeling standing on the top of a summit when you have got there under your own steam. There are probably a multitude of issues – the sense of achievement, the physical exhilaration, the solitude (I love being up there alone), the view of the landscape often largely free of human habitation, and sometimes a battle against the elements to get there.