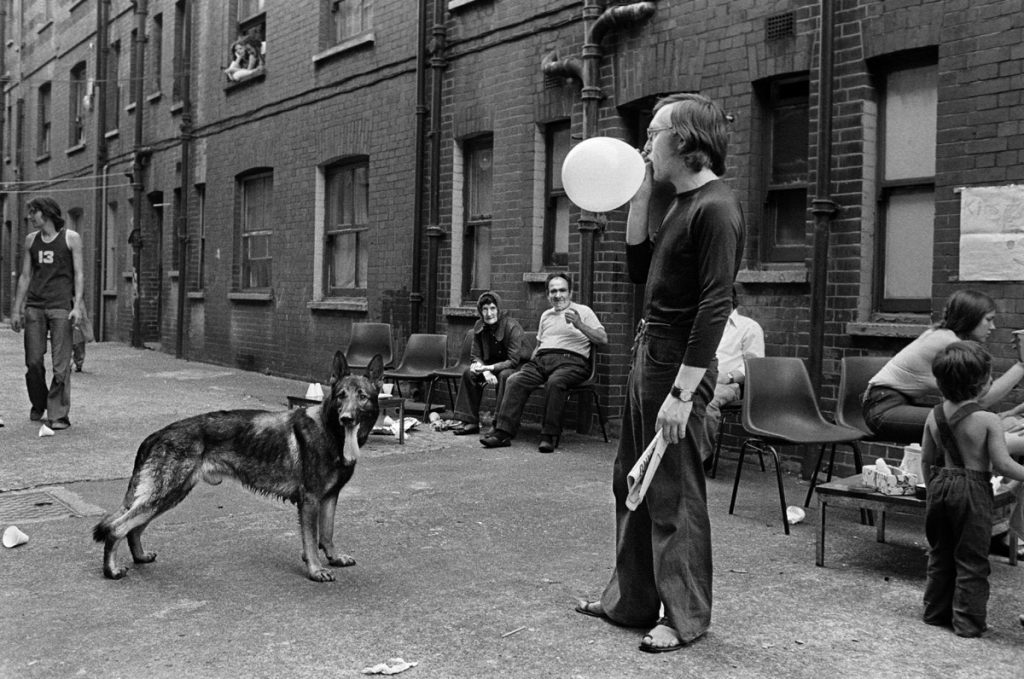

Children playing in the courtyard of the squatted tenement in Fieldgate Mansions, Aug 1985 © David Hoffman

Why can’t I write something that would awake the dead? That pursuit is what burns most deeply.

When I was a student in London in the 1970s I lived in a tenement block called Fieldgate Mansions in Whitechapel. The area was pretty run-down but had a fascinating history and a really exciting ‘alternative’ vibe. In the seventies Whitechapel was just on the cusp of transforming from a traditional Jewish neighbourhood into the home of one of London’s largest Bangladeshi communities. Whitechapel was also the scene of the notorious Ripper murders and our street was home to Rowton House, Europe’s largest night shelter for the homeless, or ‘dossers’ as they were known those days. In his ‘The People of the Abyss’ Jack London called it ‘the monster doss house’. Browsing through some old London pictures for another project I came across a gallery by a photographer called David Hoffman. I don’t recall ever meeting David, but I do recognise most of the places and some individuals in his pictures. Inspired by the images and the memories they stirred in me I wrote a kind of stream of consciousness piece, completing the first draft in one breakneck sitting. I have written it in the second person as it is essentially me addressing my younger self. There are no paragraphs as I don’t think our memories work in that way. Memories are not ordered but simply tumble out as a stream of thoughts and images. Neither does this piece have any particular narrative thread, other perhaps than allowing my mind to wander from one end of Fieldgate Gate to the other in order to see what memories are stirred up. There are numerous digressions, a bit like turning down one or other of the numerous side streets and alleyways branching off from Fieldgate Street. All the events and people mentioned are real. I am so grateful to David for agreeing to collaborate on this piece and for allowing Gareth to use some of his pictures. The piece ends up being quite a bit darker than I expected it would be. I think of this as a formative and essentially very happy period in my life, but I guess Whitechapel has darker undertones than were apparent to my teenage self. And the memory of the young heroin addict who was murdered does indeed still haunt me. We were just kids.

* * *

The streets haunt you, just as echoes of you haunt them. You walk past the bell foundry, an insinuation of holy smoke and sonorous alchemy, and into Fieldgate Street. Drunken nights walking home arms around shoulders, your talk bubbling out excitedly with butterfly ideas and suddenly-clear insights, all forgotten by the morning. You tell Sarah about the book on relativity that you just read: words, unmediated and ill-understood tumble from your mouth and vanish like soap bubbles in the night air. She feels sorry for Nixon over yesterday’s resignation, she says, despite everything he’s done. He’s just a flawed human being like the rest of us. You come to the ghost-signed shop fronts at the turning into Settles Street. Store fronts that are never open, whatever time of day you pass, yet often they echo with the sound of voices within. On the next corner a fruit and vegetable distributor, its doors always shut fast, yet still the redolent smell of ripe onions. No longer able to resist, your eyes are drawn to the other side of the road, a monolith of red brick, the fingers of its Gothic corner towers scratching at the sulphurous sky, a low canopy of purple and grey. Rowton House, Jack London’s ‘monster doss house’, stares back at you, daring you to blink. Men queue to be allowed in: a still, silent line, an air of resignation hanging over them like the aroma of an unbidden fart. Meanwhile others, occasional and individual, burst out through the doss house doors, desperate to shake off its fetid air. Here and in the surrounding streets émigré Bolsheviks still debate with Mensheviks and, smiling, secretly plot their moment of vengeance each upon the other.

Silent yet wakeful, Joseph Stalin lies in his bunk listening to the snores of Litvinov in the next cubicle. While before you on the street, his head bowed, the boots of a passing dosser beat a loose-soled tattoo against the greasy paving slabs. In your remembering eye the concrete is still slick with stir-fry oil. Was it last night, last year or some other decade? It could be any of those, but it was just here that Edinburgh Dave, he of the drooping moustache and swallowed consonants, dropped his Chinese meal as he raised an arm to greet you. Paper carrier-bag wet with grease lets go of life and the tinfoil tubs within hit the pavement with an explosion of rice and noodles. I prefer the soft ones, don’t you? Next door to the doss house is the Queen’s Head, one of those pubs bigger on the inside that the outside, and so convenient I hear you say. Katy, is that what she was called? She runs a tight ship, the dossers are allowed in when they have money in their pockets. Piss away your last penny but don’t you dare start your singing, or George will have you outside on your arse before the end of the first verse of Kevin Barry. That young man at the next table, the one with the older woman, he’s just a boy really. In his sleeveless t-shirt, he reeks of gin and testosterone. Turns out he was one who broke into your flat in Fieldgate Mansions that first evening while you were out drinking with Charlie. Leave the windows open to let in some air, he said. Second-floor flat, edging along the ledge from the landing, the pavement waiting below and it can almost taste the blood. Fuck all worth stealing anyway, but you never make that mistake again.

Fieldgate Mansions, a 19th century tenement block due to be demolished in 1972 but preserved by squatters occupying it © David Hoffman

On the lintel above the front window of the basement flat, the one below yours, is another ghost sign: N.U.W.M. An offshoot of the Communist Party, set up in the 1920s by Wal Hannington to organise against unemployment and the means test. The campaign achieved its aims in 1939, but it took the exigencies of a world war for it to do so. Take care what you wish for. Fieldgate Mansions, three blocks of four-storey flats from the Edwardian-era, one block running the length of one side of Myrdle Street and the other two on Romford Street, with a midden yard in between the two. The blocks are in a poor state and are initially ear-marked by the council for demolition. Some flats are squatted and others are snapped up on a short-term lease by City Poly students’ union to provide cheap accommodation for students. You share a flat with Charlie, a room each, a kitchen and a toilet. No bathroom and, for the first few weeks, no cooker. You eat breakfast at Mick’s Café on Fieldgate Street, drink beer at lunchtime, more beer in the evening and then a late-night curry. Some evenings you drink wine and learn to play bridge with Len and Claire from upstairs before Len goes off to his night shift at the BBC, speeding up west on his motorbike. You lose touch with Charlie and he goes on to become Gordon Brown’s press secretary. Fieldgate Mansions are not demolished but are tarted-up and taken over by a housing association. Social housing for the post-Thatcher generation with rents to match the level of aspiration. Rob Puttick’s flat is on the first floor, the ‘Fuck Off, Whatever You Want, You Can’t Have It’ sign on his door is only half in jest. Rob lives rent free in return for doing maintenance jobs for the student tenants, or at least those who shout the loudest. Astrid doesn’t shout, she asks him shyly, reluctantly and Rob agrees. A young woman, far from home, on the run and facing a punitive sentence for her peripheral role in the Rote Armee Fraktion. They marry and go their separate ways. He fixes fuse boxes and toilet cisterns for dope-mellowed students and she, as Anna Puttick, teaches East London lads how to mend cars rather than steal them. Theirs is a love story, of sorts. Rob, so kind and gentle, and Astrid, sweet-natured but lost in the aftershock of her youthful impulses. In the Hollywood version they will end up falling in love for real; the audience will see it coming, but not so the players. In the Good Samaritan with Charlie, he graduating from lager to Stolichnaya and lime, you sticking with the beer. You speak to Ash, he sits alone drinking cider. A brilliant PhD student conducting research into some unfathomable branch of physics, he has the unsettling air of someone living permanently on the edge. But the anger within is implosive rather than explosive: only Ash is menaced by the shadow of Ash.

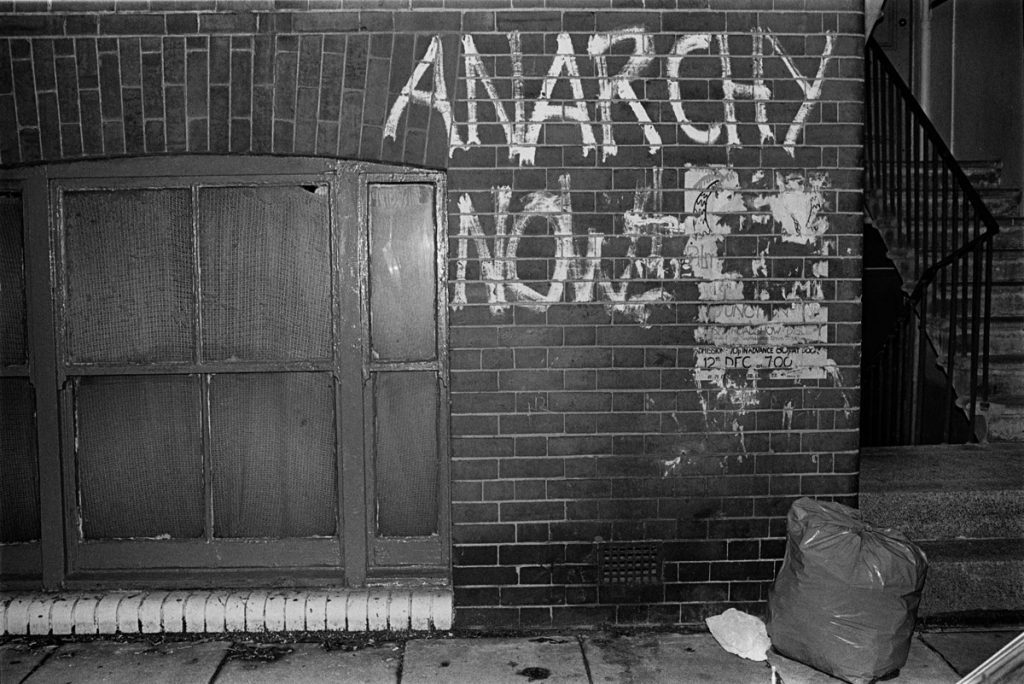

It’s a short stretch from the hospital over the road for the junior doctors to slide into the Good Sammy and wash away the daily taste of death and decay. You see a young doctor being urged, implored, coaxed by his colleagues. After a show of reluctance he agrees and the yard of ale is ordered: two and a half pints of foaming bitterness. The voices of encouragement are loud, they all know how this nightly ritual will end. Only the victim, the compliant victim, changes each evening. Joseph Merrick comes willingly; Dr Treves cannot offer him a cure for his condition at the London Hospital, but he can offer him sanctuary, a safe place to live out his remaining days. Even the joshing students fall silent when they stand before his skeleton, the distorted frame that determined the course of his life. The skeleton stares back. Merrick’s hollow eyes suck in the room’s dim light and urgently, insistently he asserts his essential humanity. For this is not the plastic facsimile in the public museum, but it is Merrick’s real bony essence, locked away in a room behind the anatomy lab. Gently the young man puts the glass to his lips, a long shaft with a bulbous end, he tilts it violently and throws back his head. He swallows some, spills more and, without a word, stumbles straight outside to vomit over his shoes. When Sarah wishes to pass unnoticed, to wander the streets like a fleeting shadow, she stuffs her flowing red locks into a faded green bush-hat. This summer you and she have become so close. But you hold back. Her boyfriend, George, is supposed to be your mate and, despite him being marooned up in Sheffield until September, you insist to yourself that he will resume both roles when he returns. Only afterwards do you realise that Sarah was in love with you too. She often stops to speak to lone dossers, though you sense she makes a point of doing so when you are together. A kind of test. In one way or another we all play to our audience, do we not? In his fifties perhaps, he is sheltering in the goods bay just along from the Good Sammy. He is from Scotland he tells you and all he possesses, you already know, is the coat on his back and the bottle of cider cradled to his breast. He wants to share his bottle with you. Sarah drinks first, just a small sip without breaking eye contact with her host, and then she passes it to you. You give the neck of the bottle a discreet wipe with your thumb as you tilt it, put it to you lips and swig. He expresses appreciation, says most everyday people would wipe the bottle before drinking it after him but he noticed, he says, that you two didn’t, and you feel guilty. Walking back to her flat you are greeted by Duncan. He kisses Sarah’s hand and bows a benediction to you both. Duncan is resourceful, a veteran of the evictions of the early seventies. He understands the power of the spectacle, a power he knows you can use against the forces that created it. When the first squatters were evicted and faced the prospect of sleeping on the streets that was precisely what they did, making sure the press and TV were there to record it. There were no more evictions. For Duncan it’s not just about squatting, it’s about enabling other people to squat: getting them into the property, dealing with the law, getting the services connected. He’s seen it all before; done it before. Everyone knows Duncan, he is the heartbeat of Fieldgate Mansions. You say your goodnights to him, standing on the pavement outside the Bangladeshi café which sits between the Queen’s Head and the butcher’s shop. Here, with Saif, you sit at a formica table and try your first samosa and jalebi. It is Saif who shows you to eat curry rolling it up into a rice ball with one hand. He teaches you how to say ‘Hello brother’ in Bangla. He regularly goes off to see his friend in West London to ‘buy money’. Saif who deserted the Pakistani army in the west and travelled across India, helped by the Naxalites, to join the Bengali rebels in the east. Saif for whom the height of praise for anyone or anything is to say that it is: ‘good enough’.

Squatters living in an old jeweller’s shop in Black Lion Yard, Whitechapel relax outside on a hot summer night © David Hoffman

Night descends. Purple and grey turns to black, the air turns chill. A metallic taste in your mouth and your eyes liquid with tears. You don’t even know her name, or if you did you’ve forgotten it, but she is a familiar figure in Fieldgate Street, selling her body to middle-aged men at cut-price rates to buy the next hit of smack. She is about the same age as you and your friends, certainly no more than twenty, a short girl with curly brown hair. One night in Myrdle Street, as you walk home late with Claudia, you see her running up the street in tears. She is naked from the waist down and tells you she has been raped: ‘a boy raped me’. The two of you comfort her and a guy you recognise comes up and puts his coat around her. An act of simple kindness swallowed up in the turmoil that ensues. A crowd gathers and someone calls the police. They arrive, take charge and, reluctantly, people drift away. The next you hear, months later, the girl with curly hair has been murdered and a man arrested. And just to the south, in Dutfield’s Yard on 30th September 1888, Elizabeth Stride is butchered by the Ripper. Years afterwards you search the records and can find no trace of the Fieldgate murder and the girl for whom this street was once home. Her name is forgotten, yet her face haunts your memories. Walking south towards the river feels like entering another realm, a place where the Kaddish is still recited and battles still fought on Cable Street. You buy a cheap but reassuringly heavy Zenit camera from the back pages of the Morning Star: a promise of ‘quality Soviet technology’. You want to record docklands before it’s all gone. You have a sense of what is about to happen to the docks and a vision of an exhibition of your work a and glossy volume of monochromatic nostalgia. You see some of these locations years afterwards rolling by as gritty car chase backdrops in episodes of The Sweeney. John Thaw, our favourite cockney copper, born in Manchester and educated at RADA.

On your second outing with your camera you wander nameless dockland streets capturing images of disused warehouses and cobbled quaysides. But you become aware of a rising uneasiness within yourself; indefinable but insistent. Soon you cut short your exploration and hurry away back to more familiar streets. You shelve the docklands project to spend more time studying for your end of year exams. Remembering only now that you never did get round to having those pictures developed. But the streets remember. Cold shadows, a creeping dread, and a brush with something you fight to lock away and keep from entering your dreams. On foggy nights, lying in bed in the room painted dark purple, you hear the ship’s horns from the Pool of London. Later, much later, you see footage of Iain Sinclair standing on Fieldgate Street in 2010 being interviewed about the refurbishment of Rowton House: Victorian poverty commodified for twenty-first century living. In the background, just within shot, a shadow of your younger self passes by. Sinclair’s left eyelid twitches in momentary awareness of a stray echo. A flickering light, a feathery brush against the skin, the hint of an evocative smell. It drifts through the streets, and you try to ignore the cry of anguish that resonates somewhere out there in the night.

This piece was first published in Unofficial Britain: Britain Uncovered in August 2018.

ABOUT THE PHOTOGRAPHER

Motivated by documenting what’s become increasingly overt state constraint on our lives, David Hoffman has spent some 40 years documenting a range of social issues from policing and racial and social conflict to homelessness drugs, poverty and exclusion. Protest, and the violence that sometimes accompanies it, is the theme that stitches his work together. Visit his website here.