This past month Psychogeographic Review has been reading:

Iain Sinclair – London Overground: A Day’s Walk Around the Ginger Line (2015)

Iain Sinclair – London Overground: A Day’s Walk Around the Ginger Line (2015)

These days Sinclair writes like a man aware that he is running out of time: words tumble out of him, one project after another, often over-lapping. There is a palpable sense of urgency in his work: the flow of words accelerates just as the pace of his walks, the groundwork that is so essential to his style of writing, seems to have speeded up. London Overground follows a typical Sinclair scenario, taking a walk along the route of London’s overground railway, the ‘ginger line’ of the title, and using it as a starting point for Sinclair’s peregrinatory riffs on writers, politics and urban life. Yes, he’s done similar London walks before, but rarely with the pace and verve of this book in which he sets out to complete the entire journey in one day. Sinclair’s companion on his walk, Boswell to his Samuel Johnson, is the film-maker Andrew Kötting, who brings a glowering physicality to Sinclair’s sensory meanderings. But, as ever with Sinclair, the words, the ideas, memories and observations, tumble forth.

Roger Willemsen – The Ends of the Earth (2010)

Roger Willemsen – The Ends of the Earth (2010)

Roger Willemsen is a respected German writer and television presenter and this is his first book to be translated into English. The Ends of the Earth comprises of series of essays reviewing the author’s travels to some of the world’s remoter corners. But this is not a simple travelogue, because Willemsen is not just a simple observer; he engages at an emotional level with the places he visits and the people he meets. So, whether it is with prostitutes in Mumbai or at a hospital death-bed in Minsk, Willemsen is fully engaged and invites us to join him, not just to gaze but to understand and empathise.

Terence Davies – Hallelujah Now (1984)

Terence Davies – Hallelujah Now (1984)

This is a fascinating read for those of us who are admirers Terence Davies’s Trilogy series of films in which he explores the life of his alter-ego, Robbie. Like the films this, his only novel to date, traces the course of Robbie’s life as he struggles to come to terms with the weight of his upbringing, his Catholicism and his sexuality in the working-class Liverpool of the fifties and sixties. Davies’s vision is clearly more fully realised in film, indeed I would suggest he is a far better film haunting glimpses into Robbie’s interior world.

Elizabeth Smart – By Grand Central Station I Sat Down and Wept (1945)

Elizabeth Smart – By Grand Central Station I Sat Down and Wept (1945)

Elizabeth Smart’s prose poem of love, longing and betrayal delivers a visceral punch that is just as relevant today as when it was first written more than half a century ago: “I have learned to smoke because I need something to hold onto.”

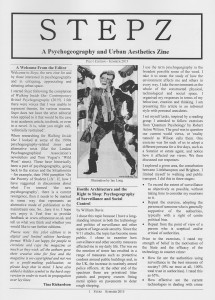

STEPZ: A Psychogeography and Urban Aesthetics Zine (Pilot Edition, Summer 2015)

STEPZ: A Psychogeography and Urban Aesthetics Zine (Pilot Edition, Summer 2015)

STEPZ is the first issue of a new zine launched by Tina Richardson to try to bring together some of the creative expressions of what she terms the new psychogeography. She succeeds in bringing together a host of new voices and some familiar ones, people interested in “critiquing, appreciating and debating urban space.”

Uniformagazine (No.3, Spring-Summer 2015)

Uniformagazine (No.3, Spring-Summer 2015)

A series of pieces on sounds, images and words each loosely connected by a sense of place: “The uniformity of presentation highlights the variations and particularity of each combination of text and image—the singularity of each work is established by its relationship to other works.”

and listening to:

Don’t Just Sing: An Anthology 1963-1999 – Karin Krog (2015)

Don’t Just Sing: An Anthology 1963-1999 – Karin Krog (2015)

Karin Krog is a Norwegian jazz singer whose CV stretches back to the early-sixties and includes work with Steve Kuhn, Red Mitchell, Dexter Gordon and Archie Shepp. Krog’s vocals have been described as sculptural and this collection amply demonstrates the way she is able to shape her voice to extract maximum effect from every syllable.

In Every Mind – A Year in the Country (2015)

In Every Mind – A Year in the Country (2015)

“This is the first audiological research and pathways case study constructed solely by A Year In The Country. In contrast to the telling of tales from the wald/wild wood in times gone by, today the stories that have become our cultural folklore we discover, treasure, pass down, are informed and inspired by, are often those that are transmitted into the world via the airwaves, the (once) cathode ray machine in the corner of the room, the zeros and ones that flitter around the world and the flickers of (once) celluloid tales. They take root in our minds and imagination via the darkened rooms of modern-day reverie, partaken of in communal or solitary séance.”

The Serpent’s Egg – Dead Can Dance (1988)

The Serpent’s Egg – Dead Can Dance (1988)

The music of Dead Can Dance is like an ethereal soundtrack meandering its way through ancient churches, stone circles and forest glades. The Serpent’s Egg is one of a string of richly textured albums band members Lisa Gerrard and Brendan Perry produced in the eighties and early-nineties and serves as a good introduction to their work.

This is Cale’s fourth solo album and arguably includes some of his best post-Velvet Underground work. A satisfying fusion of ballads, rock and the avant-garde music Paris 1919 also showcases Cale’s playful lyrics: “Somewhere between Dunkirk and Paris

Most people here are still asleep

But I’m awake

Looking out from here -at half-past France.”

and watching:

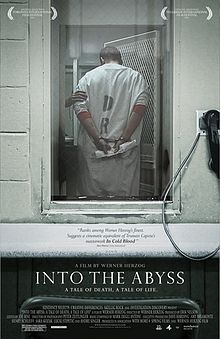

Into the Abyss – Werner Herzog (2011)

Into the Abyss – Werner Herzog (2011)

Into the Abyss is Werner Herzog’s critique of the American penal system and a powerful contribution to that nation’s debate on capital punishment. But this is not mere polemic, although Herzog is a well-known opponent of capital punishment he enables all those included in his documentary to tell their own stories in their own way.

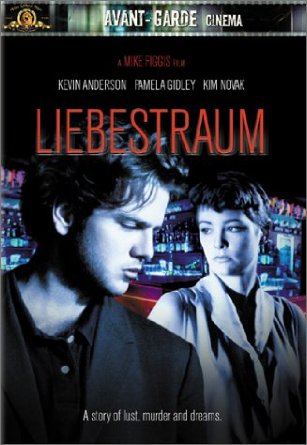

Liebestraum – Mike Figgis (1992)

Liebestraum – Mike Figgis (1992)

Liebestraum is ostensibly a thriller, but Figgis ignores any temptation to offered laboured explanations and instead concentrates on his film’s visual impact, soundtrack and moody atmosphere. In doing so he succeeds in conjuring up the ‘love dream’ of his title; and like all the best dreams it embraces love, death and architecture.

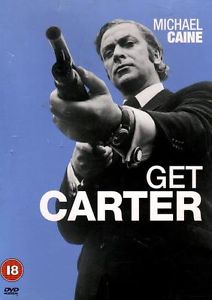

Get Carter – Mike Hodges (1971)

Get Carter – Mike Hodges (1971)

Michael Caine’s gangster, Jack Carter, is on the loose in Newcastle seeking answers and looking to exact revenge. Hodges created a genre of British crime films later taken up in movies such as The Long Good Friday and Lock, Stock and Two Smoking Barrels. But nothing quite matches Get Carter’s documentary-like evocation of provincial Britain in the 1970s, not to mention its score by Roy Budd and stand-out performances by Caine, Ian Hendry and John Osborne.