Book Review – January 2022

Those most caught up in the syndrome of work/family/machine/sport/success/failure/guilt… are those most outraged by the evolving Underground alternative.

Fifteen

I bought this book when I was fifteen and read it several times that summer. Since then it has followed me from house to house, town to town. Sometimes it has lived on a shelf, other times in a box, but I have never read it again since 1971. Until now.

I remember in my A level politics class, or British Constitution as it was called then, we were asked to stage a mock election with hustings and voting. My friend John and I spoke for the Labour Party. Two other friends, Nick and Helen, opted to represent ‘the alternative society’. I immediately decided that was much cooler and wished I’d joined their team. When it came to their turn they didn’t know quite what to say, so Nick just read out key passages from Play Power. I can’t remember who won that election, but I’m fairly sure it wasn’t the alternative society.

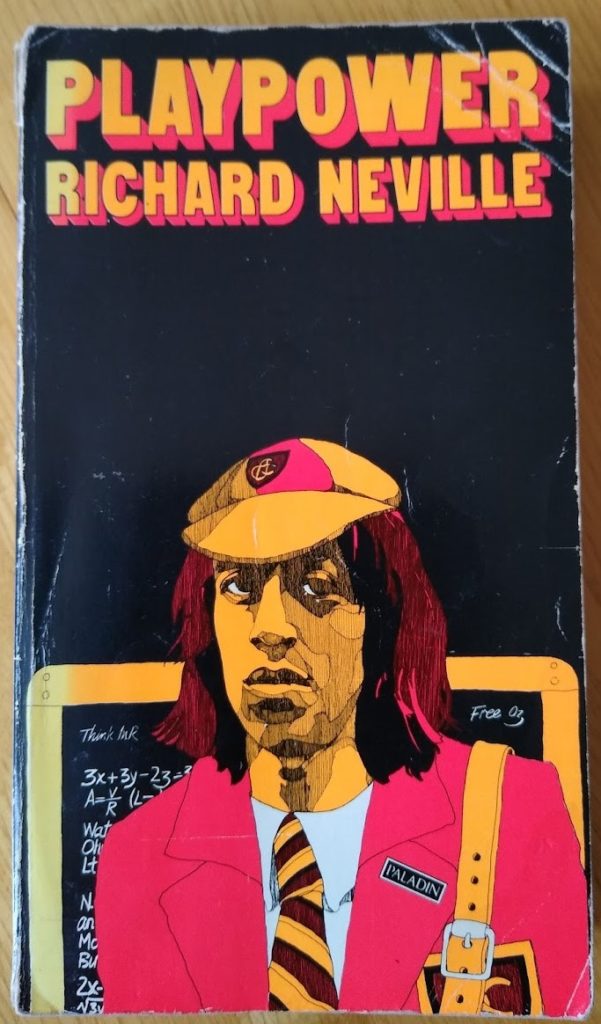

Richard Neville was born in Australia and was one of the key figures in the London-centred ‘underground’ scene of the late-1960s. As the editor of Oz magazine Neville was heavily involved in the counter-cultural movement. He and two co-defendants were convicted of obscenity in 1971 for one particularly notorious edition of Oz, but their sentences were quashed on appeal. The trial polarised opinion in Britain between the establishment and its supporters and the forces of the alternative society.

The Underground

Play Power was published that same year. Reading it again in 2022, I can say without hesitation that it still provides one of the most comprehensive reviews of the development of the 1960s underground movement and its manifestations across the world. Neville touches on music, sex and sexuality, race, politics and drugs. Despite the lazy aphorism that ‘if you can remember the sixties, you weren’t really there’, Neville was very much there and recalls it with great clarity and eloquence.

At the heart of Neville’s philosophy is the concept of ‘play’. For children play comes naturally but, as they grow and become adults, play is no longer acceptable, though it may be replaced by more formal ideas of leisure and recreation. This leaves a gap in the lives of most adults, argues Neville. For him, play is the means by which people can release their creativity, cut loose of inhibitions and have fun.

While lots of the ideas in this book are now very dated, there is something at the heart of it that was very prescient about our current situation. Neville foresaw in 1971 that, with future technological change, the worldwide economy would see greater connectedness and a massive revolution in productivity. This could result, he argues, in greater prosperity, less work, more equality and more leisure for everyone. In other words, more play. What we have, however, despite our technological advances, is greater global inequality, zero-hours contracts and more job insecurity and greater social polarisation. We live in a world with a ruined environment where absentee billionaires buy up our city centres as investments and dream of moving on from this planet to another.

The Problem

But there is a problem with this book. A very big problem. And the problem is Richard Neville himself. While some of the attitudes and language in Play Power are very much of their time, such as Neville’s frequent references to ‘chicks’, there is something far worse; something nauseatingly reprehensible. He openly boasts of having sex with a fourteen-year old schoolgirl, whom he demeans and objectifies with the descriptors ‘moderately attractive’ and ‘cherubic’. Just to be clear, this occurred when Neville was a man in his late twenties.

Neville was never held to account for his admission and died from a dementia-related illness in 2016. I have no idea whether the girl, now woman, whom he admits abusing ever complained, nor whether she is even still alive. The worrying thing, however, is that with most child abusers, the abuse is an ongoing pattern of behaviour rather than an isolated incident.

Despite its many positives, discussed above, I feel unable to wholeheartedly recommend this book. Not without flagging up this issue, anyway. In fact, I confess I feel somewhat uncomfortable about continuing to give the book house room.

A fair and nuanced review. How upsetting to find that in it – did you recall the abusive relationship being there? Books do change as we re-read them. It is very much of its time, but some things from those times we don’t want any more, of course.

I’m not sure I fully comprehended the enormity of it at the time – I suspect I was a much less worldly wise fifteen-year old than I believed I was then.

A LOT of stuff passed me by when I was 15, I have to say!!

I have a copy of this which I too haven’t looked at for decades, and having read your review I think I would struggle to engage with it now. It may have to leave the house. I know it’s of its time, and I can remember school friends of that age having relationships (although not with that age difference). However, it really isn’t acceptable then or now…

Very few of his obituaries even mention his admission of abuse, which is quite astonishing for 2016.