They’re all the same, but each one is different from every other one. You’ve got your bright mornings; your fog mornings; you’ve got your summer light and your autumn light; you’ve got your week days and your weekends; you’ve got your people in overcoats and galoshes and you’ve got your people in t-shirts and shorts. Sometimes same people, sometimes different ones. Sometimes different ones become the same, and the same ones disappear. The earth revolves around the sun and every day the light from the sun hits the earth from a different angle.

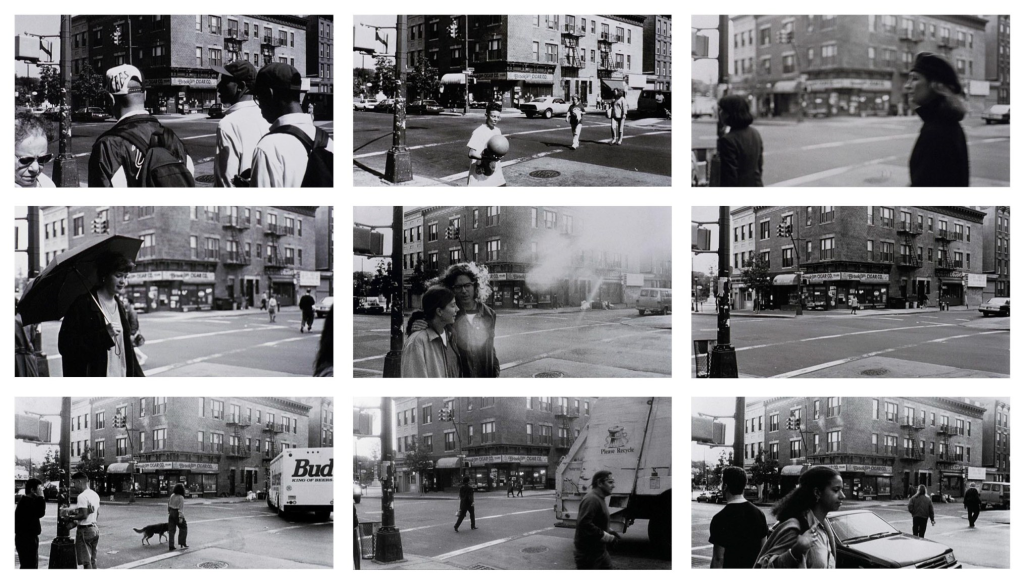

More than twenty years ago Paul Auster adapted his short story Auggie Wren’s Christmas Story to form the screenplay for Wayne Wang’s film Smoke. Both versions feature a key sub-plot which reveals one man’s beguiling obsession with the city in which he lives. Auster’s protagonist Auggie Wren, played by Harvey Keitel in the film, lives in Brooklyn and runs a tobacconist shop on the corner of Third Street and Seventh Avenue. Every day he takes his Canon 35mm SLR camera out into the street at 8.00 am and takes a picture of the same street corner, his corner, day after day.

Wren shows his album of photographs to one of his regular customers, a writer called Paul Benjamin (played by William Hurt), and tries to explain his project:

Benjamin: (leafing through the album) They’re all the same.

Wren: That’s right. More than four thousand pictures of the corner of Third Street and Seventh Avenue at eight o’clock in the morning, four thousand straight days in all kinds of weather. That’s why I can never take a vacation. I got to be in my spot every morning at the same time … every morning in the same spot at the same time.

People walking to work. The 7-Eleven truck making a morning delivery. The old guy walking his dog. And there, more than once, is Paul’s late wife, Ellen. Alive, lithe, and now dead. What is the meaning of Auggie’s odyssey? Why take the same picture every day? Auster does not give us a direct answer, at least not by way of straightforward exposition. However, the clues are all there in the screenplay. While Auggie seems to record the same scene day after day, never varying his routine, it is not in fact always the same. The cityscape Auggie frames in his lens is subject to constant change: variations in weather and light and the constant, ever-changing stream of humanity passing by.

The city, just like the lives of the people who inhabit it, has a veneer of permanence: on Auggie’s corner the days, seasons, years come and go with tedious repetition. But look a little closer and we see that the city is in the throes of constant, dynamic change and we, Auster implies, are an integral part of that ever-changing city.

We are all in the process of dying, whatever journey we choose to take through life, or whatever course is determined for us, each of us is marching forward towards our inevitable demise. So it is with cities, even as New York City grows it decays, its demise is built into the steel and concrete of its very bones. All cities rise and fall, the apparent solidity of Manhattan is but a flickering candle destined to be snuffed out in the maw of entropy:

All cities are slowly eroding, with gravity and the conspiratorial elements conspiring, and we fight a largely unseen war of attrition just to stand still.

Darran Anderson, Imaginary Cities.

Instinctively, perhaps, Auggie realises this and so presses ahead with his photographic project with no specific aim or intended destination. It will only be brought to a conclusion, we infer, when his own life reaches the end of its final reel.

In 2013, before I saw Smoke for the first time, I started a project which I called One Year. This involved taking a picture of the same scene every day for a year. The view I chose was that seen from my study window each morning at around 8.00 am just before I commenced work. The view my camera captured from my window was one of rooftops, trees and sky. I anticipated that my sequence of 365 pictures would be superficially the same but would also reflect the ever changing weather, light, colours and seasons and perhaps even show some evidence of human activity.

Several people said to me during the project and afterwards that I should have been more consistent with how I composed each shot. I seemed to have, I was told, variations in the film speed, exposure and framing and even, on occasion, some evidence of flaring on the glass of the window. More technically-minded observers even spotted when I experimented with a different camera.

In essence it was always the same scene but it was me that was the variation, I was the most obvious agent of change in each picture. The point I wanted to illustrate was that the act of taking a photograph is never neutral, it is always subject to human influence, whether that influence be deliberate or unintentional.

With One Year I was happy to flaunt every deviation from the aesthetic norm, to show the influence of the human behind the camera lens and the means whereby that process directs the way we look at a landscape. Landscape is never neutral either. Globally there are very few terrains that are not subject to some level of human manipulation.

While I was working on One Year several other people working on similar projects made contact. Cathy Dreyer, a writer and poet from Oxfordshire, decided to take the same walk from her home each day 365 times and to keep a record of it. She had been intrigued and inspired by reading Robert Macfarlane’s The Old Ways. How come he could, she mused, go off walking in all these far-flung places when he was a husband and father of young children?

Dreyer’s journey was closer to home but, in its own way, just as heroic as any of those of Macfarlane. She took the same route across the fields from her home, along footpaths and over stiles and back again. She passed the same fields, trees, hedges and streams each day. But each journey was slightly different: Dreyer noted the changes to light and vegetation that came with the gradual revolving of the seasons and the more regular changes brought about by the English weather.

But what made each walk truly unique for Dreyer was the company of her walking companions: the family dog, her children, her husband, friends and on one occasion the singer Toyah Willcox to record an episode of BBC Radio 4’s Ramblings programme. On each occasion Dreyer’s companions enabled her to see that same, familiar landscape through different eyes. By sharing her walk with each new companion Cathy Dreyer was able to encounter and perceive her local landscape in subtly new ways.

Michela Nicchiotti lives in Jebb Avenue in South London, right up against the walls of Brixton Prison. From the window of her flat she can see and hear the prisoners in their cells after they have been banged-up each evening. The shouts and calls and screams of the inmates form a constant backdrop to the lives of Nicchiotti and her fellow-residents. Perhaps even more unsettling is the fact that the prisoners, through the barred windows of their cells, can observe all the daily activities of the flat-dwellers just across the road.

Nicchiotti felt moved to embark on a project she called Through the Window. Between May 2011 and September 2012 she photographed the view from her window each day and recorded the sounds that she heard. Here is the resulting film:

Through the Window is a psychogeography project that investigates urban landscaping and the effect on emotions and behaviour of individuals, it’s the result of a personal experience, living close to the Brixton Prison, on Jebb Avenue.

Michela Nicchiotti

Nicchiotti leads us to ask who are the prisoners, the inmates of Brixton or those of us trapped within the limits of our own lives? In Smoke Paul Benjamin’s wife is dead, but she lives on as an image captured in panchromatic emulsion in Auggie Wren’s photograph album. We can record an image of a landscape and capture a moment in time. But, in a sense, Augie’s obsession to record his corner of Brooklyn captures him too; he is a prisoner of his own making. Every day at 8.00 a.m. he is there, never taking a holiday for fear of neglecting his project, never making any real friendships as he accepts no one else can quite understand his obsession.

Change, growth, entropy: all landscapes are constantly in flux. By capturing the image of his street corner day after day Auggie is able to transcend the familiar and the superficial and present deeper, more profound truths that are there to be seen, if you look hard enough, in even the most mundane of settings.

Credits

Words and One Year Montage – Bobby Seal

One Year Music – Martin Thulin

Smoke – Wayne Wang and Paul Auster (1995)

Imaginary Cities – Darran Anderson (Influx Press, 2015)

Walking in a Circle – Cathy Dreyer

Ramblings – BBC

Through the Window – Michela Nicchiotti

(Please note that YouTube has a clip from the ‘Auggie’s pictures’ section of Smoke without Spanish subtitles, but it is significantly shorter than the one I have used and misses out some key dialogue)

Great post Bobby and good to be reminded of Smoke and Auster’s short story – both favourites. Also weaving in Cathy’s Michela’s and your own project to raise interesting points about change, growth, entropy and flux. Also how repetition (& obsession) can de-familiarise the familiar and help us see things anew.

Thanks Fife – I was pleased with how the various pieces seemed to fit together!

I love the concept of recording change by staying in the same place – I really enjoyed your One Year project , and Cathy Dreyer’s project too. The images from Smoke all look very different to me, I suppose because of the people in them, whereas with your project (& Cathy Dreyer’s too) there was more sense of the subtle change of seasons – it all depends on where you choose to stand I suppose…Thanks for a very thought provoking post!

Thanks Carringtonia – I think I read somewhere that all the images used in the film were actually shot over a period of a few days, which possibly explains a lot!

Pingback: A View From The Point | Running Past

Pingback: Notes (1) | Photography 2: Documentary

Pingback: Smoke – Auggie’s Pictures | Landscape, Place and Environment