Book Review – March 2022

My creativity can be traced back to my heritage, to the skin colour that defined how I was perceived. But, like my ancestors, I wouldn’t accept defeat.

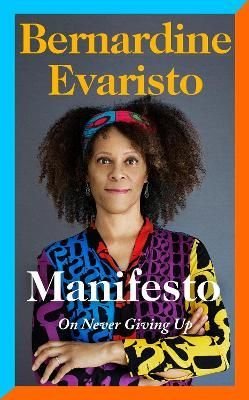

Manifesto is part memoir and part handbook providing insights into Bernardine Evaristo’s creative process. This inspirational work tells the story of her life and the influences, attitudes and ways of working that led to her eventual success as a writer. Recognition was a long time in coming and winning the Booker prize at the age of 60 was testimony of Evaristo’s commitment to never giving up.

She was born in London and raised in a family of eight children in Woolwich, a primarily white suburb. Her father was a welder from Nigeria who was active in the trade union movement and her mother a white English schoolteacher. Evaristo also embraces Irish, German and Brazilian strands in her ancestry.

As a child in the 1960s Evaristo encountered racism on a daily basis; from the thugs who regularly smashed the windows of their family home to the more subtle, but equally cruel, racist attitudes she experienced at her school and the local catholic church. But the most hurtful rejection on account of the skin colour of Bernardine and her siblings was from members of her mother’s white family who opposed her marriage to a black Nigerian.

I am first and foremost a writer, the written word is how I process everything—myself, life, society, history, politics. It’s not just a job or a passion, but it is at the very heart of how I exist in the world, and I am addicted to the adventure of storytelling as my most powerful means of communication.

Evaristo was a bright, outgoing young person who loved the theatre, literature and poetry and longed to gain a place at drama school. Her ambitions were initially thwarted and she found that too many doors at that time remained tightly shut for someone who was black, female and working class. But, true to her concept of never giving up, she kept trying and eventually secured a place at Rose Bruford College.

Once she had finished her drama degree, Evaristo found there were limited opportunities for black actors in the early 1980s. So, with two fellow graduates, she set up a black women’s theatre company. As well as acting Evaristo became involved in the management and promotion side of the company and, crucially, she found she had a talent for writing for the stage. This led eventually to becoming a full-time writer, at first creating poetry and later verse fiction. She found herself constantly pushing against the boundaries of race and gender and experimenting with new literary styles.

As a child Evaristo was a voracious reader, discovering new worlds within the covers of a book. In her teens and early twenties she sought out books that examined the reality of her own experience as a woman of colour. Very few such books were published by UK writers, but she took inspiration from the works of African American women writers and some from Nigerian writers. Later Evaristo herself wrote and published the kind of books she wanted to read but had failed to find in 1970s Britain.

In the last few chapters Evaristo lets the reader into the secrets of her creative process. Although there are no great secrets, just a set of core principles and a dedicated work ethic. She emphasises the importance of self-belief and ambition and underpins this with an openness to constructive criticism and a willingness to edit and rewrite for as many times as it takes to make one’s writing the best it can be.

In 2019 Evaristo won the Booker prize for fiction for her novel Girl, Woman, Other and now combines her own creative work with teaching and encouraging others. Despite her current status as part of the nation’s literary establishment, Bernardine Evaristo has spent most of her career as an outsider. Her race, gender, sexuality and class all provided sticks with which she was regularly beaten, But, rather than cave-in to rejection and scorn, Evaristo used it to make herself stronger and more resilient. Manifesto is a portrait of a woman who has dedicated her life to breaking down barriers and bringing people together.

Bernardine Evaristo

Bernardine Evaristo is the author of eight books of fiction and verse fiction that explore aspects of the African diaspora. Her novel Girl, Woman, Other made her the first black woman to win the Booker Prize in 2019, as well winning the Fiction Book of the Year Award at the British Book Awards in 2020, where she also won Author of the Year, and the Indie Book Award. Her writing spans reviews, essays, drama and radio. Evaristo is Professor of Creative Writing at Brunel University, London, and President of the Royal Society of Literature.

Bernardine Evaristo is the author of eight books of fiction and verse fiction that explore aspects of the African diaspora. Her novel Girl, Woman, Other made her the first black woman to win the Booker Prize in 2019, as well winning the Fiction Book of the Year Award at the British Book Awards in 2020, where she also won Author of the Year, and the Indie Book Award. Her writing spans reviews, essays, drama and radio. Evaristo is Professor of Creative Writing at Brunel University, London, and President of the Royal Society of Literature.