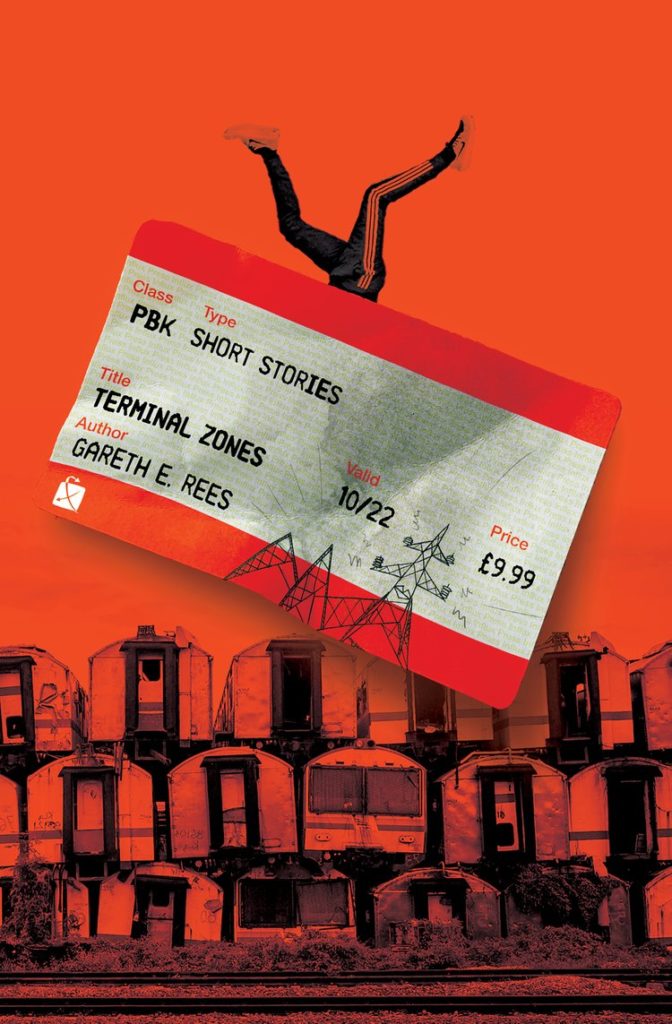

the old punk spirit that inspires the best kind of artists: if you’re dissatisfied with the culture, do something about it.

Nicholas Lezard, The Guardian

CB Editions is the brainchild of writer and publisher Charles Boyle. He also commissions, edits, typesets, designs the covers and publicises every book published, all from the living room of his house in West London. This is one of the smallest of small presses and Boyle’s aim is to publish books that he himself believes in, but that no one else will publish.

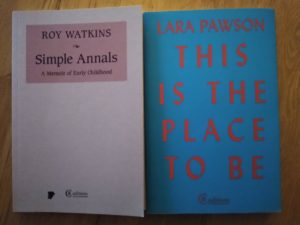

Two CB Editions books I have enjoyed recently are Simple Annals by Roy Watkins and This Is the Place to Be by Lara Pawson. Roy Watkins had several short stories published by Faber & Faber in the 1960s and has taught at universities in the UK and the United States. Simple Annals tells the story of his early childhood in Southport, Lancashire, covering the war years and into the 1950s when he reached the age of eleven. Watkins does not try to present any form of retrospective psychological analysis of his experiences, nor does he set his memoir in a social and historical context; the kind of understanding we might have when we become older. This is not the adult Watkins looking back, rather it is Roy the child sensing and feeling everything around him – the people and surroundings that form his whole world – as experienced at the time.

Too soft when Mam puts me to bed, too soft. She turns the gas low, puts things in drawers. While her back’s turned, shadows come slinking into the corners. She doesn’t know they’re there.

As Roy grows his language changes; his sentences become more coherent and his vocabulary more expansive. We see a world through a child’s eyes, a provincial working-class community which, in many of its features, no longer exists. This is a valuable historical document and an entertaining read.

Lara Pawson’s book is a very different kind of memoir. This Is the Place to Be is a fragmentary account of her time as an African correspondent for the BBC. It covers the period from 1996 to 2007 and focuses in particular on the wars in Angola and the Ivory Coast. The horrors and suffering she witnesses test her both as a journalist and as a human being and cause her to question the ethics and morality of her role.

Two doctors from Vietnam were working around the clock, tidying up blasted bone, sewing up stumps and flesh and, No, Lara they don’t want to be interviewed.

Woven into Pawson’s reminiscences are questions of identity; racial, national and gender identity. Her own somewhat androgynous look has often led to misunderstandings and abuse. She quotes James Baldwin’s thoughts on this kind of intolerance: ‘we are all androgynous … because each of us, helplessly and forever, contains the other – male in female, female in male’.

To be frank, both Simple Annals and This Is the Place to Be would struggle to find another publisher, at least not without changes of a type that would undermine the author’s original vision for the book. We have CB Editions to thank for enabling these books, and some seventy others, to see the light of day.