Dorothy Miller Richardson is a sadly neglected writer. A number of feminist critics began to take up her cause in the 1980s, but I feel it is now time that those of us who class ourselves as psychogeographers should also speak up to encourage people to read her works.

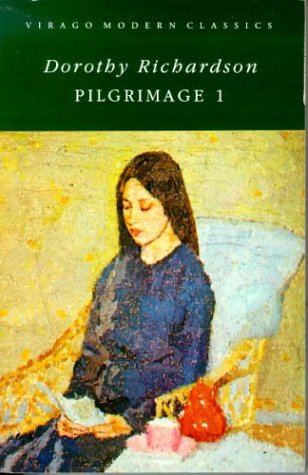

Pilgrimage Vol 1

Richardson was born in 1873 and died in 1957. Her seminal work was the sequence of 13 novels, published in 4 volumes, known collectively as Pilgrimage. Both in terms of its subject matter, the journey of one woman, and the amount of time Richardson invested in creating it, Pilgrimage can be regarded as her life’s work.

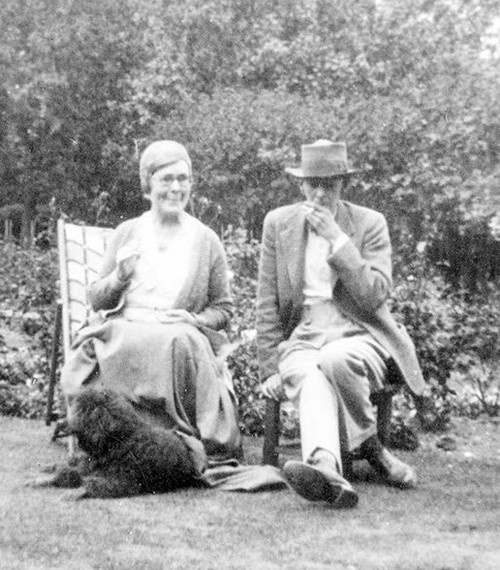

Dorothy Miller Richardson

Although born in Abingdon, Richardson is very much a London writer and, I would contend, a flâneur and a psychogeographer. New to London as a poorly-paid young woman, she walked everywhere. And as she walked, she looked, listened and absorbed, channelling her subjective impressions into her literature.

A contemporary of Virginia Woolf, Richardson was one of the early modernists. Until modernism took centre stage, there had been little or no literary depiction of urban street-life from a female viewpoint. Consequently, in terms of literary fiction, the ‘flâneuse’ was invisible and her narrative was silent. Richardson and Woolf were the key figures responsible for creating a fiction in which women characters were free to journey through and explore the streets of the city, and in doing so to delve into their own consciousness.

Pilgrimage is written from the viewpoint of Richardson’s protagonist, Miriam Henderson. She is represented as being an avid reader who looks through the words of the novels she reads to find meaning, but gradually begins to focus on the words themselves. Miriam switches from looking through the mirror to looking at the mirror and its frame. In the volume entitled The Tunnel, Richardson charts Miriam’s journey through a period of depression. Miriam struggles with the canonical texts of science and literature; rejecting the standard masculine approach but finding it difficult to develop an understanding of a feminist alternative. Pilgrimage represents Miriam’s (and by implication Dorothy Richardson’s) journey to a greater understanding of herself and of female consciousness in general.

Richardson with Alan Odle

Richardson should be considered as very much a metropolitan writer. Seven of the thirteen novels of Pilgrimage are set in the streets of Bloomsbury. The critic, Jean Radford, argues that Richardson ‘uses the city of London to represent the mind and the body of a woman’, thereby turning the streets of the city into ‘materialised history’. In other words, the city is merged into the very psychological make-up of Miriam.

As if to reflect the ever-changing nature of the modern city, Pilgrimage is written in a style that is very different from anything written before. Another contemporary, May Sinclair, described it as a ‘stream of consciousness’ novel; a term which Richardson never fully accepted.

Richardson was dissatisfied with the form of both the romantic and the realist novel. She wanted to write a novel based on her own life experiences, but to transmute it into something different by seeing it through the eyes of her protagonist, Miriam. Miriam’s voice was to replace Richardson’s. But clearly, there was still a narrator behind that voice. Richardson’s great achievement was to develop a new way of expressing her responses to the world that she saw about her. She was a modernist and a feminist. Pilgrimage has been described as the first full-scale impressionist novel.

The chronology of the thirteen volumes of Pilgrimage is interesting in that, although the events of Miriam Henderson’s life are presented chronologically, her understanding of these events – her inner journey – does not always follow this time sequence. Her psychological, and spiritual, development has a temporality of its own. Miriam’s consciousness, Richardson would argue, is emblematic of that of women as a whole.

In essence, Richardson’s London represents the maternal, and The Tunnel and Interim mark the development of a feminist critique of the patriarchal world Miriam lives in. It is her break from the lingering influence of her father. Up until this point the notion of a psychological journey, a pilgrimage, had been seen by writers in entirely male terms. The development of psychological theories and the increased freedom for women to wander through the modern city fed into the fiction of Richardson.

From Charles Baudelaire, through to Georg Simmel and Walter Benjamin, much of the critical analysis of urban life has been overshadowed by the figure of the flâneur. This concentration on the leisured, male idler of the urban public sphere, however, has given what might be regarded as a very gender specific colouring to much of the best known work on this subject. Most of the feminist criticism that has taken place since the 1960s, on the other hand, has been concerned to explore the gendered dimensions of city life and has challenged the specifically male account of flânerie. This work has added much needed questions of feminine and masculine identity to considerations of modernity in the city.

Richardson’s Miriam Henderson can certainly be described as a flâneuse. Miriam’s pilgrimage is a very personal one; a journey into her own consciousness. Her struggle to establish an independent life for herself frequently requires her to cross boundaries of gender and class. Richardson’s descriptions of Miriam’s walks through London constantly involve her in crossing roads, bridges and railway lines, as if to mirror her crossing of boundaries in her inner pilgrimage. Yet she finds the solitude of the street strangely soothing and less challenging than the other encounters in her life. Although Miriam closely observes the people she passes on the streets, she never seems to feel part of the crowd.

So I urge you, please don’t let Dorothy Richardson’s works lie neglected. Read Pilgrimage and let it take hold of you. The London streets Miriam/Dorothy walked are still there, as are many of the buildings she frequented. Why not walk those streets with her?

Like this:

Like Loading...

A Roman quay where the tidal River Dee once lapped at the city walls

A Roman quay where the tidal River Dee once lapped at the city walls