On voit un chiffonnier qui vient, hochant la tête,

Butant, et se cognant aux murs comme un poète,

Et, sans prendre souci des mouchards, ses sujets,

Epanche tout son coeur en glorieux projets.

Charles Baudelaire: ‘Le Vin de Chiffonniers’ (‘The Ragpicker’s Wine’)

Charles Baudelaire

The concept of the flâneur, the casual wanderer, observer and reporter of street-life in the modern city, was first explored, at length, in the writings of Baudelaire. Baudelaire’s flâneur, an aesthete and dandy, wandered the streets and arcades of nineteenth-century Paris looking at and listening to the kaleidoscopic manifestations of the life of a modern city. The flâneur’s method and the meaning of his activities were bound together, one with the other. Indeed, Christopher Butler suggests the flâneur is trying to achieve a form of transcendence:

the city’s modernity is most particularly defined for him by the activities of the flâneur observer, whose aim is to derive ‘l’éternel du transitoire’ (‘the eternal from the transitory’) and to see the ‘poétique dans l’historique’(‘the poetic in the historic’).

Christopher Butler, ‘Early Modernism: Literature, Music and Painting in Europe 1900 – 1916’

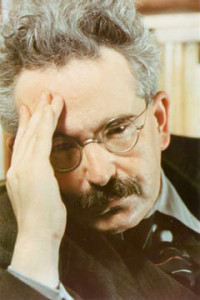

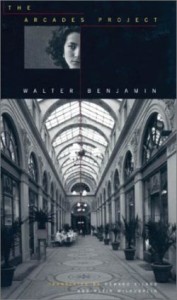

In the twentieth-century Walter Benjamin returned to the concept of the flâneur in his seminal work, The Arcades Project. This weighty, but uncompleted, study used Baudelaire’s flâneur as a starting point for an exploration of the impact of modern city life upon the human psyche. Anne Friedberg emphasises the centrality of the influence of Baudelaire’s work on that of Benjamin:

Baudelaire’s collection of poems, Les fleurs du mal (Flowers of Evil), is the cornerstone of Benjamin’s massive work on modernity, an uncompleted study of the Paris arcades. For Benjamin, the poems record the ambulatory gaze that the flâneur directs on Paris.

Anne Friedberg, ‘Les Flâneurs du Mal(l): Cinema and the Postmodern Condition’

That the arcades of Paris were long past their heyday was of no concern to Benjamin; in fact it was a key aspect of his world view that all manifestations of successive civilisations were transitory phenomena. As a consequence of this view, Benjamin saw modernity as transient too. Kirsten Seale describes Benjamin’s approach as follows:

The flâneur’s movement creates anachrony: he travels urban space, the space of modernity, but is forever looking to the past. He reverts to his memory of the city and rejects the self-enunciative authority of any technically reproduced image. The photographer’s engagement with visual technology is similarly ambivalent. The photographer reiterates the trajectory of technological advance through his or her acculturation to new technologies, yet the authority of this trajectory is challenged by photography’s product: the photograph, a material memory which is only understood by looking away from the future, by reading retrospectively.

Kirsten Seale, ‘Eye-swiping London: Iain Sinclair, Photography and the Flâneur’

Walter Benjamin

The Arcades Project is, above all else, the history of a city – Paris, the capital of the nineteenth-century, whose system of streets is a vascular network of imagination.

Peter Buse, Ken Hirschkop, Scott McCracken and Bernard Taithe, ‘Benjamin’s Arcades: An Unguided Tour’

In The Arcades Project, Benjamin puts forward two complementary concepts to explain our human response to modern city life. Erlebnis can be characterised as the shock-induced anaesthesia brought about by the overwhelming sensory bombardment of life in a modern city, somewhat akin to the alienated subjectivity experienced by a worker bound to his regime of labour. Erfahrung is a more positive response and refers to the mobility, wandering or cruising of the flâneur; the unmediated experience of the wealth of sights, sounds and smells the city has to offer. Benjamin was interested in the dialectic between these two concepts and cited Baudelaure’s poetry as a successful medium for turning erlebnis into erfahrung. As Benjamin wrote in his section of Illuminations entitled On Some Motifs in Baudelaire:

The greater the share of the shock factor in particular impressions, the more constantly consciousness has to be alert as a screen against stimuli; the more efficiently it does so, the less do these impressions enter experience (Erfahrung), tending to remain in the sphere of a certain hour in one’s life (Erlebnis).

Walter Benjamin, ‘Illuminations’

For Benjamin, the environment of the city, in particular the arcades of Paris, provided the means to provoke lost memories of times past:

it is the material culture of the city, rather than the psyche, that provides the shared collective spaces where consciousness and the unconscious, past and present, meet.

Susan Buck-Morss, ‘The Flâneur, the Sandwichman and the Whore: The Politics of Loitering’

Not all critics accept the veracity of Benjamin’s analysis. Martina Lauster, for instance, feels that Benjamin’s flâneur device gives too much importance to only one aspect of Baudelaire’s work and ignores the significance of other nineteenth-century writers such as Poe. She suggests that Benjamin’s idea of the flâneur is not only of limited value for an understanding of the twentieth-century urban experience, but can be seen positively to hamper it. This negative effect, she argues, comes about from Benjamin’s mistaken application of the modernist aesthetic concept of self-loss. As a result, instead of informing urban modernism about itself, Benjamin’s work serves only to obscure it.

However, Lauster does accept the importance of The Arcades Project in assembling excerpts from nineteenth-century sources dealing with the phenomena of novelty – in particular the arcades and department stores, panoramas, exhibitions, fashion, and gaslight. In accepting the importance of these observations, Lauster seems to concede the relevance of their source – the strolling spectator who collects mental notes taken on leisurely city walks and transcribes them into written form; in other words, the flâneur:

In short, they resemble observations of a flaneur, the viewer who takes pleasure in abandoning himself to the artificial world of high capitalist civilization. One could describe this figure as the viewing-device through which Benjamin formulates his own theoretical assumptions concerning modernity, converging in a Marxist critique of commodity fetishism.

Martina Lauster, ‘Walter Benjamin’s Myth of the Flâneur’

What we can be clear about is that Benjamin does not just write about the flâneur but, in The Arcades Project, he writes as a flâneur. As noted earlier, he metaphorises his textual practice into ragpicking, unearthing ‘the rags, the refuse’ from his extensive reading, his cutting and pasting from all manner of sources, into the text of this, his best known work. The origins of The Arcades Project are in the textual detritus of Benjamin’s research; a method that echoes Baudelaire’s ragpicker and which he refers to when he writes that:

poets find the refuse of society on their street and derive their heroic subject from this very refuse. This means that a common type is, as it were, superimposed upon their illustrious type. … Ragpicker or poet — the refuse concerns both.

Walter Benjamin, ‘Charles Baudelaire: A Lyric Poet in the Era of High Capitalism’

The ragpicker is recurring motif in Benjamin’s writing and offers a useful metaphor for his textual methodology. Benjamin focuses on the margins of the modern city, scavenging amongst the texts and oral histories that have been omitted or neglected. Literary ragpicking resurrects discarded texts, forming them into new texts. Benjamin was interested not just in what is, but in what was and what might be. He is looking for where the imagined city meets the material one.

- Paris – Passage de Choiseul

In his exploration of the ‘imagined city’, Benjamin assigns particular importance to thresholds. Ancient peoples had access to numerous rites of passage, transition points and triggers for being jolted from one state of consciousness to another; from reason to myth. Modern people have grown poorer in this regard, but Benjamin saw the perambulations of the flâneur as a contemporary equivalent; the practice of flânerie, in other words, can facilitate a way through significant psychological and spiritual thresholds. In the same regard, Benjamin also referred to the power of advertising and its dreamlike quality; its capacity to link commodities with the human imagination. Thus, in entering the world created by advertising, one passes through a threshold, thereby achieving a form of transcendence:

Modern idlers attempt a kind of partial transcendence – imitating the gods – that temporarily overcomes the shock experience of modernity.

Peter Buse, Ken Hirschkop, Scott McCracken and Bernard Taithe, ‘Benjamin’s Arcades: An Unguided Tour’

In The Arcades Project and his exploration of Paris’s arcades, Benjamin writes of outside spaces that mirror the inside of buildings and vice versa. Hence his belief in the importance of the arcades; he believed they were able to bring together all manner of consumer commodities in an environment of mixed interiors and exteriors. As a result, Benjamin enjoyed posing questions such as whether the tables outside a café in an arcade were indoors or outdoors. He was concerned with the spatial, suggesting that the flâneur experiences the streets as an interior. This interior unites all epochs, all parts of the world and all phenomena of contemporary society. The flâneur, Benjamin argues, can be intoxicated by one glance, which stimulates his very being and results in a physical internalisation of the material world of commodities.

Cafes, cinemas and shops in which one is invited to browse, such as bookshops, all have in common that they can be seen as an extension of the street. Benjamin enjoyed such ambiguity. He applauded the development of new ‘dream spaces’, such as leisure parks, wax museums, and department stores and saw them all as products of a new commodity culture and as places that beckoned the flâneur.

Taking the concept of ‘dream space’ one step further, Benjamin argues that gambling has a key psychological role to play in this new commodity culture. On the one hand it is clearly a short-sighted and self-destructive occupation. But on the other, it gives the promise and anticipation of a utopian dream with many options and possibilities, and an aura pregnant with notions of superstition and fate.

Leeds – County Arcade

For Benjamin, the flâneur is the primary tool for interpreting modern culture. He is the observer, the witness, the stroller of the commodity-obsessed marketplace. He synchronises himself with the shock experience of modern life. He does not, however, challenge that system. The point of the flâneur, argues Benjamin, is to lead us toward an ‘awakening’ – the moment at which the past and present recognise each other; to erfahrung. His tool for achieving this is einfühlung – empathy:

Empathy with the commodity is fundamentally empathy with the exchange value itself. The flâneur is the virtuoso of this empathy.

Walter Benjamin, ‘The Arcades Project’

As noted earlier, Benjamin believed that one of the main tasks of his writing was to rescue the cultural heritage of the past in order to understand the present; not just the cultural treasures of the past, but the detritus and other discarded objects:

Benjamin the surrealist collects together the images of the city that the flâneur presents to him, to be left with a vast array of past objects, buildings and spaces that he then attempts to reassemble into illuminating order.

Deborah Parsons, ‘Streetwalking the Metropolis: Women, the City and Modernity’

Thus, we create a history which is not just that of the victor. He posits the flâneur as a key motif for urban modernist writing. Benjamin’s writings are peopled by two types of flâneur – the bourgeois wanderer of the arcades and his vagrant counterpart, the rag-picker. These are used, asserts Deborah Parsons, as vehicles for his speculations on urban modernity:

Both are itinerant metaphors that register the city as a text to be inscribed, read, rewritten and reread. The flâneur walks idly through the city, listening to its narrative. The rag-picker too moves across the urban landscape, but as a scavenger, collecting, rereading and rewriting its history.

Deborah Parsons, ‘Streetwalking the Metropolis: Women, the City and Modernity’

Flânerie was not without its ideological opponents: authoritarian regimes in particular objected to any expression of loitering or idleness, seeing it as a manifestation of subversion; Hitler, for example, banned both prostitutes and vagrants from the streets. The loiterer refuses to submit to thee social controls of modern industry:

Boredom in the production process originates with its speed-up (through machines).The flaneur with his ostentatious composure protests against the production process.

Walter Benjamin, ‘The Arcades Project’

Flâneurs ignore the rush hour; rather than hurrying off somewhere, they hang around. Their very being ‘is a demonstration against the division of labour.’ They demonstrate the resistance of the daydreamer to the rise of industry and commerce.

The early manifestation of flânerie was brief, being concurrent with the time when the arcades where at their height of fashion. Benjamin was, however, not concerned with nostalgia for the past, but with developing the critical knowledge necessary for a revolutionary break from history’s most recent configuration. He claimed the past was illuminated only when ‘lit by the present’, and the converse was equally true: “Every present is determined by those [past] images which are synchronic with it” (ibid. p. 458)

Map of Paris, 1900

By describing the flâneur’s vision of the city as phantasmagoric, Benjamin seems to suggest that it is a dream-like vision akin to that provided in theatrical entertainment. He also reminds us of Marx’s metaphorical description of the commodity as having the power of a religious fetish; an item that owes its magical status to the imaginative power of the human brain which confers magical powers upon it, at the same time as venerating the fetish, as an autonomous object. Phantasmagoric experiences, therefore, are created by humans, but have the appearance of seeming to possess a life of their own. This, suggests Benjamin, as exactly the same as Marx’s theory of the commodity coming to acquire the appearance of an independent life of its own as a result of the nature of social relationships that produce it.

But the approach of the flâneur is not overtly political. Whilst Engels, in his The Condition of the Working Class in England in 1844, maps out Manchester, street by street, hovel by hovel, with forensic detail, Baudelaire’s peregrinations around Paris are conducted in a much more abstract, poetic fashion. The flâneur exists in that space between the physical and the imaginary. However, as Guy Debord shows in the post-war period, some of the methodology of the flâneur can be very political. The flâneur’s defining characteristics are evident not in the expression, but the desire. The flâneur is undirected and motiveless, in that his or her motivation is simply the desire to wander. The flâneur can be said to represent both decadence and impoverishment.

And whilst Baudelaire’s Paris was destroyed in the mid nineteenth-century by Haussmann’s massive programme of urban renewal, it is still Paris, more than any other city, that is associated with flânerie. The flâneur’s role, one can argue, is symbolic. Physical wandering has parallels in intellectual exploration and, it can be said, the spirit of the flâneur is present in the intellectual curiosity of the bohemian; the bohemian-flâneur takes advantage of comparative affluence to explore different ideas and lifestyles. In twentieth century Paris, the bars and cafés of the Left Bank were the haunt of bohemians and flâneurs.

It is, therefore, clear that Baudelaire established a tradition that moved through the early modernists, to the Surrealists and on to the Situationists. As part of the latter movement, Guy Debord developed the notions of the dérive and the ‘spectacle’. A dérive (in English ‘drift’) is the means by which ‘psycho-geographies’ are achieved. A drift is an unplanned walk, usually through a city or marginal area, and a psycho-geography involves the walker creating a mental map of the city which:

depends on the walker ‘seeing’ and being drawn into events, situations and images by an abandonment to wholly unanticipated attraction.

Chris Jenks (ed), ‘Visual Culture’

Contemporary British writers, such as Iain Sinclair, have used this methodology to write about London. Sinclair continues the tradition of the flâneur and writes about his dérives across the East End and elsewhere in a style which owes much to the influence of Benjamin and the French situationists. His walks map out what he refers to as an ‘alternative cartography’, a process for which the situationists used the word psychogeography. In London Orbital, Sinclair introduces the notion of ‘eye-swiping’ – scanning the urban landscape for creative material. The term suggests the avaricious sweep of the flâneur’s eye, scooping up material for later transcription.

Sinclair’s walks suggest that the flâneur may have survived beyond the death-knell that Benjamin sounded for its practitioner. The flâneur has clearly adapted to conditions in the contemporary city, and absorbed developments in visual technology. Sinclair, in the tradition of the Baudelairean flâneur, has assimilated into his method new means of collecting and cataloguing information from the everyday. Such projects may, in fact, be easier than they were for previous generations of flaneur; the modern subject is comfortable with the presence and the use of photographic equipment. The camera is no longer exotic; it belongs to the sphere of the familiar.

Guy Debord, seeking to bring together Marxism, psychology and an analysis of the impact of rapid technological advance, all interlaced with Benjamin’s ideas, describes this process as being about:

This society which eliminates geographical distance reproduces distance internally as spectacular separation.

Guy Debord, ‘Society of the Spectacle’

But whilst Benjamin’s flâneur, the idle wanderer of the arcades or the ragpicker combing the liminal spaces of the city, may have disappeared, Susan Buck-Morss insists that the flâneur’s spirit lives on:

If the flaneur has disappeared as a specific figure, it is because the perceptive attitude which he embodied saturates modern existence, specifically, the society of mass consumption (and is the source of its illusions). The same can be argued for all of Benjamin’s historical figures. In commodity society all of us are prostitutes, selling ourselves to strangers; all of us are collectors of things.

Susan Buck-Morss, ‘The Flâneur, the Sandwichman and the Whore: The Politics of Loitering’

Images

Leeds image by the author, all others sourced under Creative Commons

Bibliography

Walter Benjamin, The Arcades Project (Cambridge, Mass and London, Belknap Harvard, 1999)

Walter Benjamin, Charles Baudelaire: A Lyric Poet in the Era of High Capitalism (New York and London, Verso Books, 1997)

Walter Benjamin, Illuminations (London, Pimlico, 1999)

Walter Benjamin, The Writer of Modern Life: Essays on Charles Baudelaire (Cambridge, Mass and London, Belknap Harvard, 2006)

Peter Brooker, Modernity and Metropolis: Writing, Film and Urban Formations (Basingstoke and New York, Palgrave, 2002)

Peter Buse, Ken Hirschkop, Scott McCracken and Bernard Taithe, Benjamin’s Arcades: An Unguided Tour (Manchester University Press, Manchester and New York, 2005)

Guy Debord, Society of the Spectacle (Detroit, Black & Red, 1977)

Chris Jenks (ed), Visual Culture (London and New York, Routledge, 1995)

Ian Munro, The Figure of the Crowd in early Modern London: The City and its Double (New York, Palgrave MacMillan, 2005)

Deborah Parsons, Streetwalking the Metropolis: Women, the City and Modernity (Oxford and New York, Oxford University Press, 2000)

Raymond Williams, The Country and the City (Oxford, Oxford University Press, 1973)

Journal Articles

Susan Buck-Morss, ‘The Flâneur, the Sandwichman and the Whore: The Politics of Loitering’, New German Critique, No. 39, Second Special Issue on Walter Benjamin (Autumn, 1986), pp. 99-140

Paul Castro, ‘Flânerie and Writing the City in Iain Sinclair’s Lights Out for the Territory, Edmund White’s The Flâneur, and José Cardoso Pires’s Lisboa: Livro de Bordo’, Darwin College Research Report, Cambridge (October 2003)

Deborah Epstein Nord, ‘The Urban Peripatetic: Spectator, Streetwalker, Woman Writer’, Nineteenth-Century Literature, University of California Press,Vol. 46, No. 3, Dec., 1991, pp. 351-375

Anne Friedberg, ‘Les Flâneurs du Mal(l): Cinema and the Postmodern Condition’, PMLA, Vol. 106, No. 3 (May, 1991), pp. 419-431

Martina Lauster, ‘Walter Benjamin’s Myth of the Flâneur’ The Modern Language Review, Vol. 102, No. 1 (Jan., 2007), pp. 139-156

Frank Mort and Miles Ogborn, ‘Transforming Metropolitan London, 1750–1960’ The Journal of British Studies, University of Chicago, Vol. 43, No. 1 (January 2004), pp. 1-14

Janice Mouton, ‘From Feminine Masquerade to Flâneuse: Agnès Varda’s Cléo in the City’, Cinema Journal, University of Texas Press, Vol. 40, No. 2, Winter, 2001, pp. 3-16

Elizabeth Munson, ‘Walking on the Periphery: Gender and the Discourse of Modernization’ Journal of Social History, Vol. 36, No. 1 (Autumn, 2002), pp. 63-75

Wendy Parkins, ‘Moving Dangerously: Mobility and the Modern Woman’, Tulsa Studies in Women’s Literature, University of Tulsa, Vol. 20, No. 1 (Spring, 2001), pp. 77-92

Kirsten Seale, ‘Eye-swiping London: Iain Sinclair, Photography and the Flâneur’, Literary London: Interdisciplinary Studies in the Representation of London, Vol. 3, No. 2 (September 2005)

Janet Wolff, ‘The Invisible Flâneuse: Women and the Literature of Modernity’, Theory, Culture and Society, vol. 2, no. 3, 1985, pp. 37–46

Like this:

Like Loading...