What is psychogeography, anyway? My understanding of the concept is three-fold: it is a theory, a practice and a body of evidence. The most interesting of these, for me, is the body of evidence: the books, works of art and reportage that enable us to understand and engage with the social and geographical environment in which we live. Thus, at Psychogeographic Review I write about the novels, poems, maps, photographs, paintings, films and music that help us to construct a living map of the places where humans live. The following is my personal and very subjective list of some of the books that have informed this discussion in 2023.

The Flow: Rivers, Water and Wildness by Amy-Jane Beer

As a biologist, a nature writer and a kayaker Amy-Jane Beer has spent much of her life in and around water. But it was the tragic death of her friend, Kate, in a kayaking accident on the River Rawthey in Cumbria on New Year’s Day 2012 that proved to be the eventual catalyst for her to write The Flow. Kate’s death was a shattering blow to Beer and caused her to fall out of love with rivers and paddling. Several years later, while visiting the scene of her friend’s death, Beer has a sense of Kate’s presence, but not the catharsis she had hoped for. She was inspired, however, to embark on the travels and research that led to this book. Just like water The Flow eddies, swirls and percolates. And, as with water, Beer’s narrative meanders along across 400 pages, sometimes gentle, other times powerful, but always relentless in its cyclical lifeforce. She moves effortlessly from science to mythology, embracing nature and human activity and weaving in her own personal story.

and around water. But it was the tragic death of her friend, Kate, in a kayaking accident on the River Rawthey in Cumbria on New Year’s Day 2012 that proved to be the eventual catalyst for her to write The Flow. Kate’s death was a shattering blow to Beer and caused her to fall out of love with rivers and paddling. Several years later, while visiting the scene of her friend’s death, Beer has a sense of Kate’s presence, but not the catharsis she had hoped for. She was inspired, however, to embark on the travels and research that led to this book. Just like water The Flow eddies, swirls and percolates. And, as with water, Beer’s narrative meanders along across 400 pages, sometimes gentle, other times powerful, but always relentless in its cyclical lifeforce. She moves effortlessly from science to mythology, embracing nature and human activity and weaving in her own personal story.

Edging the City by Peter Finch

During the 2020 Covid lockdown Welsh government rules meant that none of us could travel outside the boundaries of our own local authority without good reason. Being a seasoned jobbing writer, Finch seized on this situation as the perfect opportunity for a new project, rather than worrying about it being a limitation on the walking trips that had become so much part of his writing process. Finch had read and was intrigued by Iain Sinclair’s London Orbital back in 2002. Sinclair wrote about a circular walk he completed around the outer edge of London following a route as close as possible to that of the M25 motorway. The walk revealed new aspects of the city and took Sinclair through unfamiliar liminal zones, each very different in character to the London that he thought he knew. Finch, a life-long resident of Cardiff, felt that a similar journey around the border of his own city might result in new insights about it. Not just discoveries about the edges of Cardiff and the places where it butts up against neighbouring boroughs, but more general insights into the nature of borderlands.

The Edge of Cymru: A Journey – by Julie Brominicks

The journey described in The Edge of Cymru took place over a 12-month period in 2012 and 2013 and was prompted by the opening of the new Wales Coast Path. By linking the northern and southern ends of the coastal path with a walk along the Welsh-English border, Brominicks took on the challenge of walking over 1,000 miles around the edge of Cymru. She admits that she put very little planning into the actual journey and simply walked for several hours each day and pitched her small tent wherever she found a suitable spot. On most weekends she would be joined by her partner, Rob, and every few days she would return by bus to her home in Machynlleth to shower, clean her clothes, renew her supplies and, when required, sign on. Brominicks has spent the years since completing her journey researching the political, social, economic and natural history of Wales. The fruits of this research are skilfully woven into the narrative of her book and transform it into something that is much more than a simple description of walking trip. But it is Julie Brominicks’s own journey, her inner reflections, that make The Edge of Cymru such a compelling read.

Real Dorset by Jon Woolcott

Many of us think we know Dorset from past seaside holidays or from travelling to a Dorset port to catch a boat across the English Channel. But do we really know this ancient county with its Ryme Intrinsica, Beer Hackett and other fever dream villages? Is the ancient green hinterland beyond the coastal resorts really just part of the imaginary Wessex of William Barnes and Thomas Hardy? But Dorset resident and writer Jon Woolcott knows this county inside out, having travelled much of it by bike and on foot. But, like other books in the Real series, this is no conventional travel guide. Woolcott makes a point of seeking out the quirky and the overlooked; places that rarely make the glossy county guide books, but which nonetheless capture the essence of Dorset. In Real Dorset Woolcott travels the byways of his home county finding the topographical threads to tug at in order to reveal the temporal layers beneath.

The Instant by Amy Liptrot

The Instant picks up where Liptrot’s previous memoir, The Outrun, left off. The former details how she returned from London to the family farm in Orkney to overcome her alcoholism with hard manual labour, cold water swimming and the security of a familiar place. Now sober and a successful writer, Liptrot feels there is still something missing in her life. She is reluctant to admit to herself that what she lacks is something as simple and conventional as a relationship with a significant other, but she suspects that is indeed the case. She travels to Berlin, a city awash with other drifters, seekers and creatives. She finds cheap accommodation and spends her time walking, birdwatching and people watching. She also trawls the dating apps obsessively and embarks on a series first dates, with varying degrees of success. The Instant is a painfully humane account of alienation, loneliness and self-discovery in our current digital age.

details how she returned from London to the family farm in Orkney to overcome her alcoholism with hard manual labour, cold water swimming and the security of a familiar place. Now sober and a successful writer, Liptrot feels there is still something missing in her life. She is reluctant to admit to herself that what she lacks is something as simple and conventional as a relationship with a significant other, but she suspects that is indeed the case. She travels to Berlin, a city awash with other drifters, seekers and creatives. She finds cheap accommodation and spends her time walking, birdwatching and people watching. She also trawls the dating apps obsessively and embarks on a series first dates, with varying degrees of success. The Instant is a painfully humane account of alienation, loneliness and self-discovery in our current digital age.

Crimes of Cymru: Classic Mystery Tales of Wales – Edited by Martin Edwards

Crimes of Cymru is a collection of fourteen stories first published between 1909 and the 1980s. Among the better-known Welsh-born authors featured are Roald Dahl, Ethel Lina White and Arthur Machen. Other Welsh writers, less well-known but equally prolific, include Cledwyn Hughes and Jack Griffith. The rest of the collection is made up by writers from other parts of Britain who set some of their short stories in Wales. This includes Christianna Brand, Ianthe Jerrold and Michael Gilbert. The short stories presented vary in style and length and, it has to be said, they are of variable quality too. But I think the whole point was to present a representative picture of Welsh crime fiction in the twentieth century, some of the work good and some necessarily not quite so good. In fulfilling this objective Martin Edwards has fully succeeded and has produced a very entertaining collection with an extremely helpful introduction and notes on each author.

Brittle With Relics: A History Of Wales 1962 – 1997 by Richard King

Brittle With Relics is, perhaps, the best ever portrait of Wales in the late twentieth century. This is oral history at its most incisive and revealing. Some of King’s interviewees are household names: Neil Kinnock, Peter Hain, Dafydd Iwan and Leanne Wood, for instance. Others are less well-known but are nonethelees important to the strands of the story that King weaves together. Activists, and in particular women, from the Welsh language campaign, miners’ support groups, the second homes campaign and CND are given great prominence. The final two decades of the twentieth century witnessed several crucial steps in Wales’s journey towards re-asserting its national identity and for the Welsh to recover their self confidence as a people. This process resulted in the creation of a Welsh National Assembly and Assembly Government in 1999, which later evolved into the nation’s Senedd and Welsh Government. Prior to this, the Welsh Language Act of 1993 put Welsh on an equal footing with English for the first time and , incrementally, began to reverse the decline of the Welsh language. The establishment of a Welsh language television channel, S4C, had already brought Welsh into the daily discourse of both native speakers and learners from 1982 onwards.

This is oral history at its most incisive and revealing. Some of King’s interviewees are household names: Neil Kinnock, Peter Hain, Dafydd Iwan and Leanne Wood, for instance. Others are less well-known but are nonethelees important to the strands of the story that King weaves together. Activists, and in particular women, from the Welsh language campaign, miners’ support groups, the second homes campaign and CND are given great prominence. The final two decades of the twentieth century witnessed several crucial steps in Wales’s journey towards re-asserting its national identity and for the Welsh to recover their self confidence as a people. This process resulted in the creation of a Welsh National Assembly and Assembly Government in 1999, which later evolved into the nation’s Senedd and Welsh Government. Prior to this, the Welsh Language Act of 1993 put Welsh on an equal footing with English for the first time and , incrementally, began to reverse the decline of the Welsh language. The establishment of a Welsh language television channel, S4C, had already brought Welsh into the daily discourse of both native speakers and learners from 1982 onwards.

Gathering of the Tribe: Landscape by Mark Goodall

Gathering of the Tribe is a series of books by Mark Goodall in which he explores music and soundscapes which are capable of triggering altered states and mystical experiences. Each volume comprises a series of essays examining records selected from his personal collection. Volume 1, Acid, focuses on music and psychedelic drugs. This second volume, Landscape, takes as its premise the powerful effect that a particular landscape, be it urban or rural, can have on a creative mind. The albums discussed are mainly from artists most of us would regard as obscure and esoteric, although better known works by John Cage, Basil Kirchin and early Pink Floyd are also featured. It is difficult to write about music, and writing about the kind of music that Goodall himself concedes is ‘obscure and difficult’ is even more of a challenge. The great success of this collection of essays, however, is that makes you want to go out and track down these recordings and listen to them.

Welcome to New London by John Rogers

Fully ten years after his last book, This Other London, film maker, vlogger and psychogeographer John Rogers takes to print again with another consideration of his favourite subject matter: London. Welcome to New London focuses in particular on the changes wrought to East London by the legacy of the 2012 Olympics. Rogers vividly captures the struggle for the future of this part of the city and examines the contest of ownership and identity between local residents and developers as well as the ongoing fight for survival by nature. He guides us through the neglected corners of London, taking time out to investigate the capital’s concealed rivers and the cultural significance of graffiti. Rogers clearly has no illusions about the negative aspects of London, but his love for the city’s flawed beauty shines through.

psychogeographer John Rogers takes to print again with another consideration of his favourite subject matter: London. Welcome to New London focuses in particular on the changes wrought to East London by the legacy of the 2012 Olympics. Rogers vividly captures the struggle for the future of this part of the city and examines the contest of ownership and identity between local residents and developers as well as the ongoing fight for survival by nature. He guides us through the neglected corners of London, taking time out to investigate the capital’s concealed rivers and the cultural significance of graffiti. Rogers clearly has no illusions about the negative aspects of London, but his love for the city’s flawed beauty shines through.

Revolutionary Spirit: A Post-Punk Exorcism by Paul Simpson

Paul Simpson was a key figure in the Liverpool music scene of the late 1970s and early 1980s. He played with Will Sergeant and Ian McCulloch before they launched Echo and the Bunnymen and he then formed The Teardrop Explodes with Julian Cope before going on to put together his own band, The Wild Swans. Despite critical acclaim, penning one of the best singles of the 1980s (in my opinion) in Revolutionary Spirit, a strong following in Liverpool and, we read in Simpson’s record of those years, an odd pocket of popularity in the Philippines, success ultimately eluded the Swans. This is a very readable account of a fascinating and influential time and place in post-punk music. Simpson underpins this story with some frank disclosures, by way of exorcism perhaps, about his difficulties with mental health and his relationship with his father.

Paul Simpson was a key figure in the Liverpool music scene of the late 1970s and early 1980s. He played with Will Sergeant and Ian McCulloch before they launched Echo and the Bunnymen and he then formed The Teardrop Explodes with Julian Cope before going on to put together his own band, The Wild Swans. Despite critical acclaim, penning one of the best singles of the 1980s (in my opinion) in Revolutionary Spirit, a strong following in Liverpool and, we read in Simpson’s record of those years, an odd pocket of popularity in the Philippines, success ultimately eluded the Swans. This is a very readable account of a fascinating and influential time and place in post-punk music. Simpson underpins this story with some frank disclosures, by way of exorcism perhaps, about his difficulties with mental health and his relationship with his father.

Like this:

Like Loading...

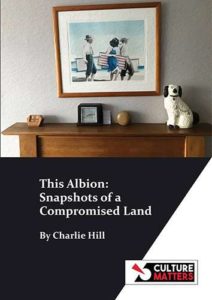

Charlie Hill is an author from Birmingham. He has written long and short form memoir, and contemporary, historical and experimental fiction. He is the co-founder and former Director of a literary festival, the PowWow Festival of Writing, which ran from 2011 to 2017 and featured guests such as Joanne Harris, Alex Wheatle, Stewart Home and Natalie Haynes. He has also appeared at many such events, including Frankfurt’s Literaturm and the Birmingham Literary Festival.

Charlie Hill is an author from Birmingham. He has written long and short form memoir, and contemporary, historical and experimental fiction. He is the co-founder and former Director of a literary festival, the PowWow Festival of Writing, which ran from 2011 to 2017 and featured guests such as Joanne Harris, Alex Wheatle, Stewart Home and Natalie Haynes. He has also appeared at many such events, including Frankfurt’s Literaturm and the Birmingham Literary Festival.

Clevelode is Paul Newland and his collaborators. Newland was one-half of The Lowland Hundred, a critically acclaimed duo that released three albums, Under Cambrian Sky (2010), Adit (2011), The Lowland Hundred (2014).

Clevelode is Paul Newland and his collaborators. Newland was one-half of The Lowland Hundred, a critically acclaimed duo that released three albums, Under Cambrian Sky (2010), Adit (2011), The Lowland Hundred (2014).

Jon Woolcott is a writer and publisher and currently works for the independent publisher, Little Toller, where he also edits The Clearing, the online journal for new writing about place and nature. He is the author of

Jon Woolcott is a writer and publisher and currently works for the independent publisher, Little Toller, where he also edits The Clearing, the online journal for new writing about place and nature. He is the author of

Gareth E. Rees is the author of Unofficial Britain, longlisted for the Ondaatje Prize and one of The Sunday Times best books of the year 2020. He’s also the author of Car Park Life, The Stone Tide and Marshland. His first short story collection, Terminal Zones, was published in 2022 and examines the strangeness of everyday life in a time of climate change

Gareth E. Rees is the author of Unofficial Britain, longlisted for the Ondaatje Prize and one of The Sunday Times best books of the year 2020. He’s also the author of Car Park Life, The Stone Tide and Marshland. His first short story collection, Terminal Zones, was published in 2022 and examines the strangeness of everyday life in a time of climate change

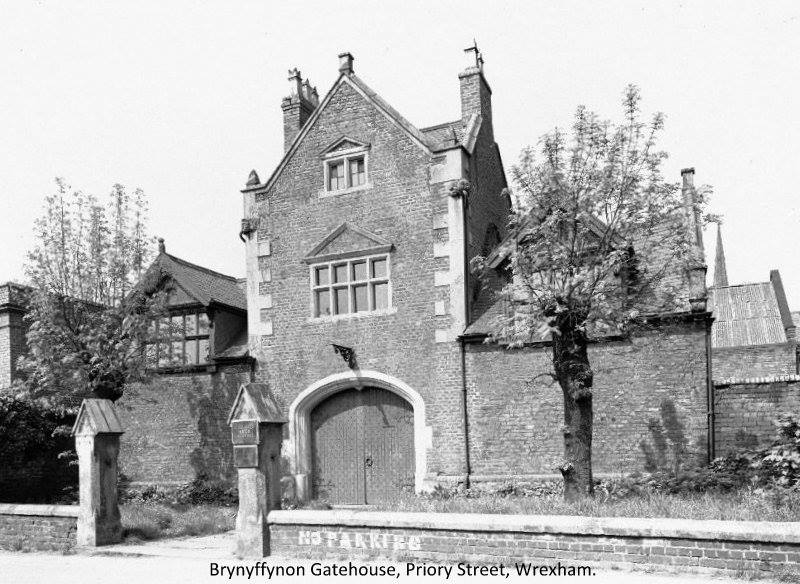

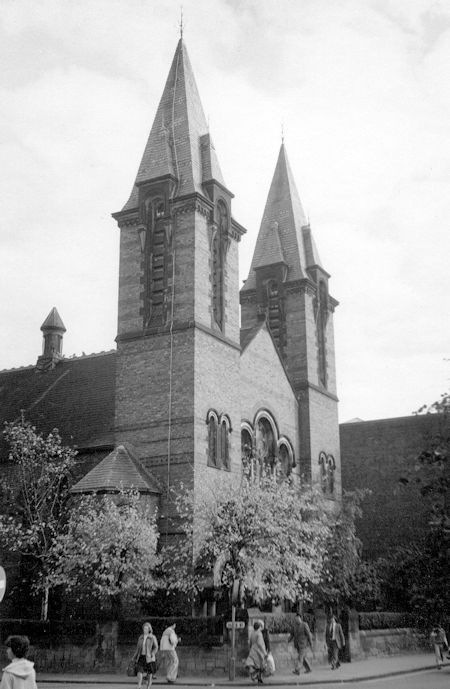

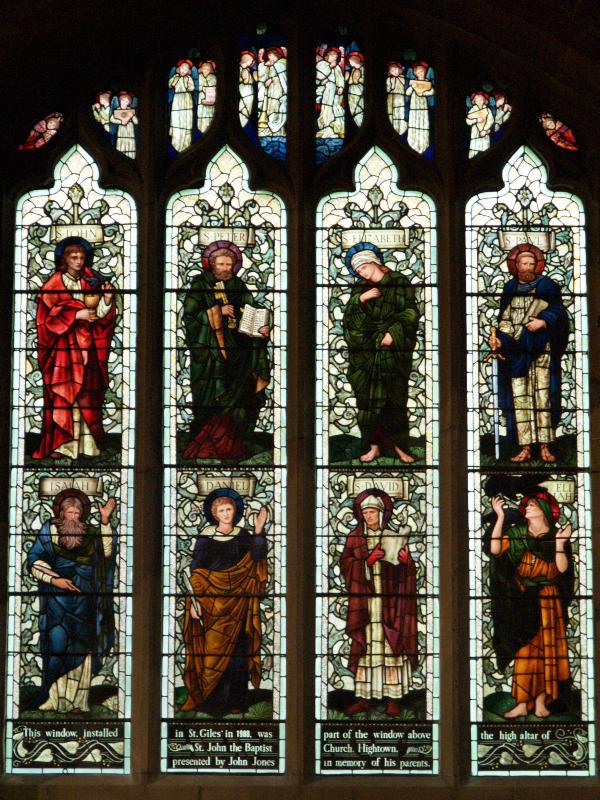

In a similar fashion, a slew of other buildings have been reduced to rubble in recent decades. When the Hightown flats were built in the 1960s they were praised for their innovative design concept. The concrete components of the 191 flats were factory-built and assembled on site creating light, airy homes each forming part of a small, neighbourly cluster. Lack of investment in the 1980s and 1990s, however, caused the fabric of the flats to steadily deteriorate and they were demolished in 2011.

In a similar fashion, a slew of other buildings have been reduced to rubble in recent decades. When the Hightown flats were built in the 1960s they were praised for their innovative design concept. The concrete components of the 191 flats were factory-built and assembled on site creating light, airy homes each forming part of a small, neighbourly cluster. Lack of investment in the 1980s and 1990s, however, caused the fabric of the flats to steadily deteriorate and they were demolished in 2011.

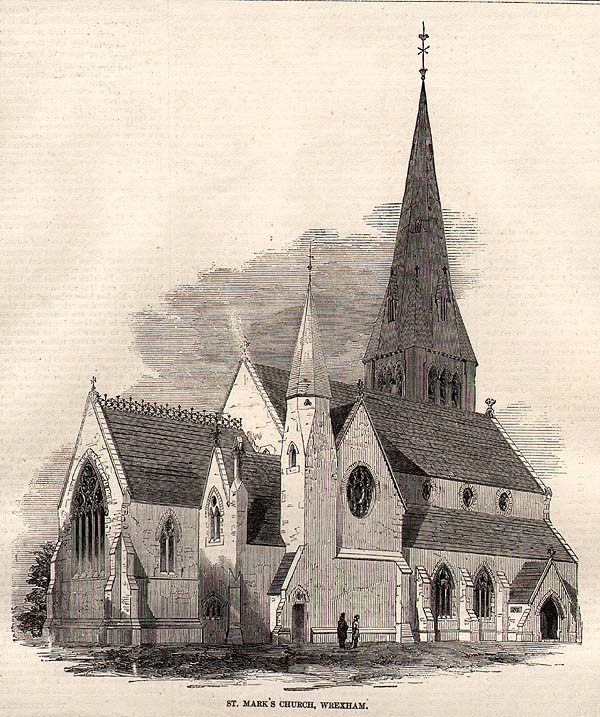

From a much earlier era, several of the Wrexham area’s large country houses have met a similar fate.

From a much earlier era, several of the Wrexham area’s large country houses have met a similar fate.

The Vegetable Market, an indoor market hall built in 1898 with a mock-Tudor frontage was demolished in the 1980s to make way for a shopping centre.

The Vegetable Market, an indoor market hall built in 1898 with a mock-Tudor frontage was demolished in the 1980s to make way for a shopping centre.

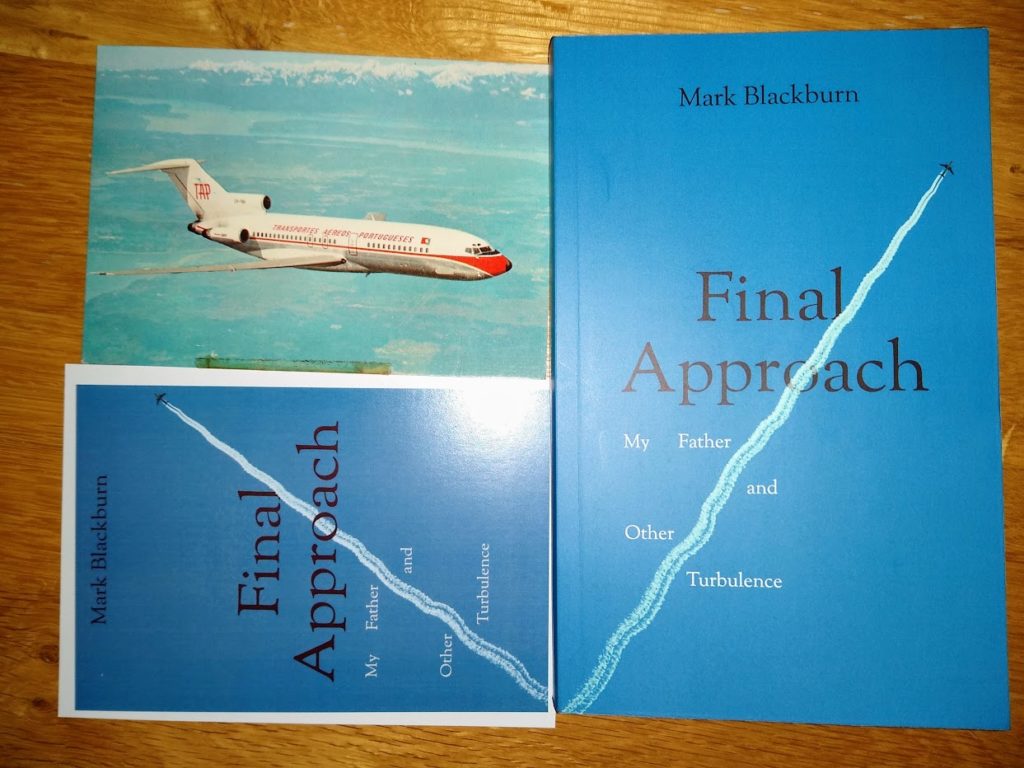

Mark grew up in Berkshire but, arriving in London during the heyday of punk to study at the LSE, he felt that was where he belonged. Sundry abortive attempts at stardom followed, as a stand-up comedian, actor and musician. A successful career there as a shoe-seller followed, but Mark now lives in Somerset, England, doing what he loves best – writing. He has written a number of short stories, poems and other pieces of creative non-fiction which have been published online and in print.

Mark grew up in Berkshire but, arriving in London during the heyday of punk to study at the LSE, he felt that was where he belonged. Sundry abortive attempts at stardom followed, as a stand-up comedian, actor and musician. A successful career there as a shoe-seller followed, but Mark now lives in Somerset, England, doing what he loves best – writing. He has written a number of short stories, poems and other pieces of creative non-fiction which have been published online and in print. and around water. But it was the tragic death of her friend, Kate, in a kayaking accident on the River Rawthey in Cumbria on New Year’s Day 2012 that proved to be the eventual catalyst for her to write The Flow. Kate’s death was a shattering blow to Beer and caused her to fall out of love with rivers and paddling. Several years later, while visiting the scene of her friend’s death, Beer has a sense of Kate’s presence, but not the catharsis she had hoped for. She was inspired, however, to embark on the travels and research that led to this book. Just like water The Flow eddies, swirls and percolates. And, as with water, Beer’s narrative meanders along across 400 pages, sometimes gentle, other times powerful, but always relentless in its cyclical lifeforce. She moves effortlessly from science to mythology, embracing nature and human activity and weaving in her own personal story.

and around water. But it was the tragic death of her friend, Kate, in a kayaking accident on the River Rawthey in Cumbria on New Year’s Day 2012 that proved to be the eventual catalyst for her to write The Flow. Kate’s death was a shattering blow to Beer and caused her to fall out of love with rivers and paddling. Several years later, while visiting the scene of her friend’s death, Beer has a sense of Kate’s presence, but not the catharsis she had hoped for. She was inspired, however, to embark on the travels and research that led to this book. Just like water The Flow eddies, swirls and percolates. And, as with water, Beer’s narrative meanders along across 400 pages, sometimes gentle, other times powerful, but always relentless in its cyclical lifeforce. She moves effortlessly from science to mythology, embracing nature and human activity and weaving in her own personal story.

details how she returned from London to the family farm in Orkney to overcome her alcoholism with hard manual labour, cold water swimming and the security of a familiar place. Now sober and a successful writer, Liptrot feels there is still something missing in her life. She is reluctant to admit to herself that what she lacks is something as simple and conventional as a relationship with a significant other, but she suspects that is indeed the case. She travels to Berlin, a city awash with other drifters, seekers and creatives. She finds cheap accommodation and spends her time walking, birdwatching and people watching. She also trawls the dating apps obsessively and embarks on a series first dates, with varying degrees of success. The Instant is a painfully humane account of alienation, loneliness and self-discovery in our current digital age.

details how she returned from London to the family farm in Orkney to overcome her alcoholism with hard manual labour, cold water swimming and the security of a familiar place. Now sober and a successful writer, Liptrot feels there is still something missing in her life. She is reluctant to admit to herself that what she lacks is something as simple and conventional as a relationship with a significant other, but she suspects that is indeed the case. She travels to Berlin, a city awash with other drifters, seekers and creatives. She finds cheap accommodation and spends her time walking, birdwatching and people watching. She also trawls the dating apps obsessively and embarks on a series first dates, with varying degrees of success. The Instant is a painfully humane account of alienation, loneliness and self-discovery in our current digital age.

This is oral history at its most incisive and revealing. Some of King’s interviewees are household names: Neil Kinnock, Peter Hain, Dafydd Iwan and Leanne Wood, for instance. Others are less well-known but are nonethelees important to the strands of the story that King weaves together. Activists, and in particular women, from the Welsh language campaign, miners’ support groups, the second homes campaign and CND are given great prominence. The final two decades of the twentieth century witnessed several crucial steps in Wales’s journey towards re-asserting its national identity and for the Welsh to recover their self confidence as a people. This process resulted in the creation of a Welsh National Assembly and Assembly Government in 1999, which later evolved into the nation’s Senedd and Welsh Government. Prior to this, the Welsh Language Act of 1993 put Welsh on an equal footing with English for the first time and , incrementally, began to reverse the decline of the Welsh language. The establishment of a Welsh language television channel, S4C, had already brought Welsh into the daily discourse of both native speakers and learners from 1982 onwards.

This is oral history at its most incisive and revealing. Some of King’s interviewees are household names: Neil Kinnock, Peter Hain, Dafydd Iwan and Leanne Wood, for instance. Others are less well-known but are nonethelees important to the strands of the story that King weaves together. Activists, and in particular women, from the Welsh language campaign, miners’ support groups, the second homes campaign and CND are given great prominence. The final two decades of the twentieth century witnessed several crucial steps in Wales’s journey towards re-asserting its national identity and for the Welsh to recover their self confidence as a people. This process resulted in the creation of a Welsh National Assembly and Assembly Government in 1999, which later evolved into the nation’s Senedd and Welsh Government. Prior to this, the Welsh Language Act of 1993 put Welsh on an equal footing with English for the first time and , incrementally, began to reverse the decline of the Welsh language. The establishment of a Welsh language television channel, S4C, had already brought Welsh into the daily discourse of both native speakers and learners from 1982 onwards.

psychogeographer John Rogers takes to print again with another consideration of his favourite subject matter: London. Welcome to New London focuses in particular on the changes wrought to East London by the legacy of the 2012 Olympics. Rogers vividly captures the struggle for the future of this part of the city and examines the contest of ownership and identity between local residents and developers as well as the ongoing fight for survival by nature. He guides us through the neglected corners of London, taking time out to investigate the capital’s concealed rivers and the cultural significance of graffiti. Rogers clearly has no illusions about the negative aspects of London, but his love for the city’s flawed beauty shines through.

psychogeographer John Rogers takes to print again with another consideration of his favourite subject matter: London. Welcome to New London focuses in particular on the changes wrought to East London by the legacy of the 2012 Olympics. Rogers vividly captures the struggle for the future of this part of the city and examines the contest of ownership and identity between local residents and developers as well as the ongoing fight for survival by nature. He guides us through the neglected corners of London, taking time out to investigate the capital’s concealed rivers and the cultural significance of graffiti. Rogers clearly has no illusions about the negative aspects of London, but his love for the city’s flawed beauty shines through. Paul Simpson was a key figure in the Liverpool music scene of the late 1970s and early 1980s. He played with Will Sergeant and Ian McCulloch before they launched Echo and the Bunnymen and he then formed The Teardrop Explodes with Julian Cope before going on to put together his own band, The Wild Swans. Despite critical acclaim, penning one of the best singles of the 1980s (in my opinion) in Revolutionary Spirit, a strong following in Liverpool and, we read in Simpson’s record of those years, an odd pocket of popularity in the Philippines, success ultimately eluded the Swans. This is a very readable account of a fascinating and influential time and place in post-punk music. Simpson underpins this story with some frank disclosures, by way of exorcism perhaps, about his difficulties with mental health and his relationship with his father.

Paul Simpson was a key figure in the Liverpool music scene of the late 1970s and early 1980s. He played with Will Sergeant and Ian McCulloch before they launched Echo and the Bunnymen and he then formed The Teardrop Explodes with Julian Cope before going on to put together his own band, The Wild Swans. Despite critical acclaim, penning one of the best singles of the 1980s (in my opinion) in Revolutionary Spirit, a strong following in Liverpool and, we read in Simpson’s record of those years, an odd pocket of popularity in the Philippines, success ultimately eluded the Swans. This is a very readable account of a fascinating and influential time and place in post-punk music. Simpson underpins this story with some frank disclosures, by way of exorcism perhaps, about his difficulties with mental health and his relationship with his father.

Martin Edwards was born at Knutsford, Cheshire and educated in Northwich and at Balliol College, Oxford. A member of the Murder Squad (collective of crime writers, Martin was the longest-serving Chair of the Crime Writers’ Association since its founder John Creasey. In 2015 he was elected eighth President of the Detection Club; his predecessors include G.K. Chesterton, Dorothy L. Sayers, and Agatha Christie. He is Archivist of the CWA and of the Detection Club and consultant to the British Library’s Crime Classics.

Martin Edwards was born at Knutsford, Cheshire and educated in Northwich and at Balliol College, Oxford. A member of the Murder Squad (collective of crime writers, Martin was the longest-serving Chair of the Crime Writers’ Association since its founder John Creasey. In 2015 he was elected eighth President of the Detection Club; his predecessors include G.K. Chesterton, Dorothy L. Sayers, and Agatha Christie. He is Archivist of the CWA and of the Detection Club and consultant to the British Library’s Crime Classics.

Richard King is the author of Original Rockers (shortlisted for the Gordon Burn Prize and a Rough Trade, The Times and Uncut Book of the Year), How Soon Is Now? (the Sunday Times Music Book of the Year) and The Lark Ascending (a Rough Trade, Mojo and Evening Standard Book of the Year, shortlisted for the Penderyn Prize). He was born into a bilingual family in South Wales and for the last twenty years has lived in the rural county of Powys, in mid-Wales.

Richard King is the author of Original Rockers (shortlisted for the Gordon Burn Prize and a Rough Trade, The Times and Uncut Book of the Year), How Soon Is Now? (the Sunday Times Music Book of the Year) and The Lark Ascending (a Rough Trade, Mojo and Evening Standard Book of the Year, shortlisted for the Penderyn Prize). He was born into a bilingual family in South Wales and for the last twenty years has lived in the rural county of Powys, in mid-Wales.