Book Recommendations

Darran Anderson – Imaginary Cities (2015)

Darran Anderson – Imaginary Cities (2015)

Darran Anderson’s Imaginary Cities is a weighty, erudite book which propels the reader on an exhilarating journey through the history of the city in art, architecture and the human imagination. But, like some literary conjuror, Anderson has managed to produce a volume which wears its extensive and meticulous research lightly. He also places examples from popular culture, such as Judge Dredd and The Jetsons, alongside the more esoteric and academic. But why not? Anderson suggests that the buildings which did not get beyond the drawing board, those that remain within the realm of the imagination, are just as significant as those that were actually built: “The boundary between ‘real life’ architectural settings and fiction has been an intriguingly porous one.” After all, every structure, whether real or imagined, will eventually end up in the dustbin of history. Just one small carp, however: although the book is backed up by a slick website and lively Twitter account, it would have been nice to have included some pictures and an index.

Stuart Braun – City of Exiles (2015)

Stuart Braun – City of Exiles (2015)

Stuart Braun’s book raises important questions concerning the influence of place on the human psyche and the nature of belonging. Berlin is, indeed, a city of exiles: from the Huguenots through to today’s Syrian refugees, outsiders have sought sanctuary in Berlin and each wave of exiles has left its mark upon the city. As Braun puts it:

Berlin is Berlin because of its strangers, its wanderers, its many displaced people who have come to build a kind of safe haven. These free-flowing exiles are the source of the freedom so many feel when they come to Berlin – they are the city’s substance in a sense.

Iain Sinclair – London Overground: A Day’s Walk Around the Ginger Line (2015)

Iain Sinclair – London Overground: A Day’s Walk Around the Ginger Line (2015)

These days Sinclair writes like a man aware that he is running out of time: words tumble out of him, one project after another, often over-lapping. There is a palpable sense of urgency in his work: the flow of words accelerates just as the pace of his walks, the groundwork that is so essential to his style of writing, seems to have speeded up. London Overground follows a typical Sinclair scenario, taking a walk along the route of London’s overground railway, the ‘ginger line’ of the title, and using it as a starting point for Sinclair’s peregrinatory riffs on writers, politics and urban life. Yes, he’s done similar London walks before, but rarely with the pace and verve of this book in which he sets out to complete the entire journey in one day. Sinclair’s companion on his walk, Boswell to his Samuel Johnson, is the film-maker Andrew Kötting, who brings a glowering physicality to Sinclair’s sensory meanderings. But, as ever with Sinclair, the words, the ideas, memories and observations, tumble forth.

Louisa Treger – The Lodger (2014)

Louisa Treger – The Lodger (2014)

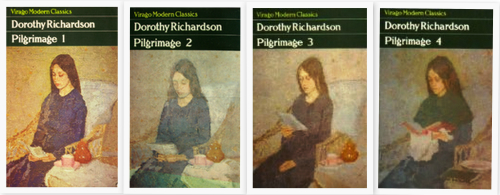

While studying for her PhD thesis on Virginia Woolf Louisa Treger stumbled upon a review by Woolf of a writer whose name she did not recognise. The review was of Revolving Lights, the seventh volume in Dorothy Richardson’s Pilgrimage sequence of novels. Treger sought out Pilgrimage and was immediately riveted:

Who was Dorothy Richardson? How had she come to re-invent the English language in order to record the experience of being uniquely female?

The Lodger, Treger’s first novel, tries to answer that question. It is ‘a melding of fact and fiction’ exploring a critical period in the life of Dorothy Richardson. She bases her story on the biographical facts of Richardson’s life, most of that life shadowed by Miriam Henderson, Richardson’s protagonist in Pilgrimage.

Tina Richardson – Walking Inside Out: Contemporary British Psychogeography (Place, Memory, Affect) (2015)

Tina Richardson – Walking Inside Out: Contemporary British Psychogeography (Place, Memory, Affect) (2015)

Tina Richardson is one of the key figures in contemporary British psychogeography and urban aesthetics. In this book she has brought together fourteen essays from a diverse range of urban walkers and writers. But this is not just a rag-bag collection of writings; Richardson’s own contributions give shape and form to the collection. For those of us interested in psychogeography she has provided a map of where we have come from and some pointers towards where we are going. More than anything else Walking Inside Out is a call to action:

Psychogeography does not have to be complicated. Anyone can do it. You do not need a map, Gore-Tex, rucksack, or companion. All you need is a curious nature and a comfortable pair of shoes. There are no rules to doing psychogeography – this is its beauty.

Claire-Louise Bennett – Pond (2015)

Claire-Louise Bennett – Pond (2015)

I first encountered Claire-Louise Bennett in the pages of gorse magazine and ever since I have looked forward to reading this, her debut collection of stories. The wait was worthwhile: Pond is a book that lives on in one’s imagination long after one has finished reading it. It is a collection of stories presented to the reader by an unnamed female narrator, but Bennett pushes the short story form to its absolute limits. In doing so she has achieved a work of profound and unsettling beauty:

Still, as I’ve said, none of this has anything to do with now whatsoever. I don’t know what it has to do with and as a matter of a fact I’m not sure what now is about either.

Music Recommendations

Sub-Lingual Tablet – The Fall (2015)

Sub-Lingual Tablet – The Fall (2015)

This is The Fall’s thirty-first album and is something of a return to form. Mark E Smith is at his irascible, snarling best and the band operates as a tight, punchy unit filling in the aural spectrum and leaving Smith’s voice free to wander in and out of his songs as only he can. Smith’s lyrics are totally unique and his subject matter is consistently idiosyncratic. Take Venice With The Girls, for instance:

Long nights in Brit-land

Olderness, his skin, whose is it

Too beautiful

Best thing, best thing for to do is hide

Instrumentals – Flying Saucer Attack (2015)

Instrumentals – Flying Saucer Attack (2015)

No lyrics, no song titles, no ‘songs’ to speak of. Nothing, in fact, to get in the way of David Pearce’s sonic wash of guitars, tapes and ambient effects. As the first FSA album in 15 years Instrumentals feels like something of a place-holder, but a very enjoyable one for all that.

In Every Mind – A Year in the Country (2015)

In Every Mind – A Year in the Country (2015)

“This is the first audiological research and pathways case study constructed solely by A Year In The Country. In contrast to the telling of tales from the wald/wild wood in times gone by, today the stories that have become our cultural folklore we discover, treasure, pass down, are informed and inspired by, are often those that are transmitted into the world via the airwaves, the (once) cathode ray machine in the corner of the room, the zeros and ones that flitter around the world and the flickers of (once) celluloid tales. They take root in our minds and imagination via the darkened rooms of modern-day reverie, partaken of in communal or solitary séance.”

Surface Tension – Rob St John (2015)

Surface Tension – Rob St John (2015)

Sometimes with a project of this ambition it seems the initial concept overshadows the final creative achievement. Thankfully this is not the case with this, Rob St John’s sublime multi-modal work. As he describes it: “Surface Tension is a project I have been working on since last summer, exploring the River Lea in East London through sound, writing and photography. Commissioned by the Thames21 charity’s ‘Love the Lea’ campaign, Surface Tension uses field recordings, tape loops, analogue synth, 120 and pinhole film photography to creatively interpret water pollution.”

Alasdair Roberts – ‘Alasdair Roberts’ (2015)

Alasdair Roberts – ‘Alasdair Roberts’ (2015)

Incredibly, this is Scottish singer/songwriter/guitarist Alasdair Roberts’s eighth solo album. He’s also done any number of collaborations too; he’s clearly a hard-working performer, though he’s yet to do a gig in my part of the world. Many of Roberts’s previous works have included traditional folk songs but this is an album of his own material. It is a very satisfying and mellow collection with sparse acoustic arrangements and deeply personal lyrics, though Roberts mischievously wanted to know how I knew they were so personal when I first reviewed this album earlier in the year.

Weaving – Jo Johnson (2014)

Weaving – Jo Johnson (2014)

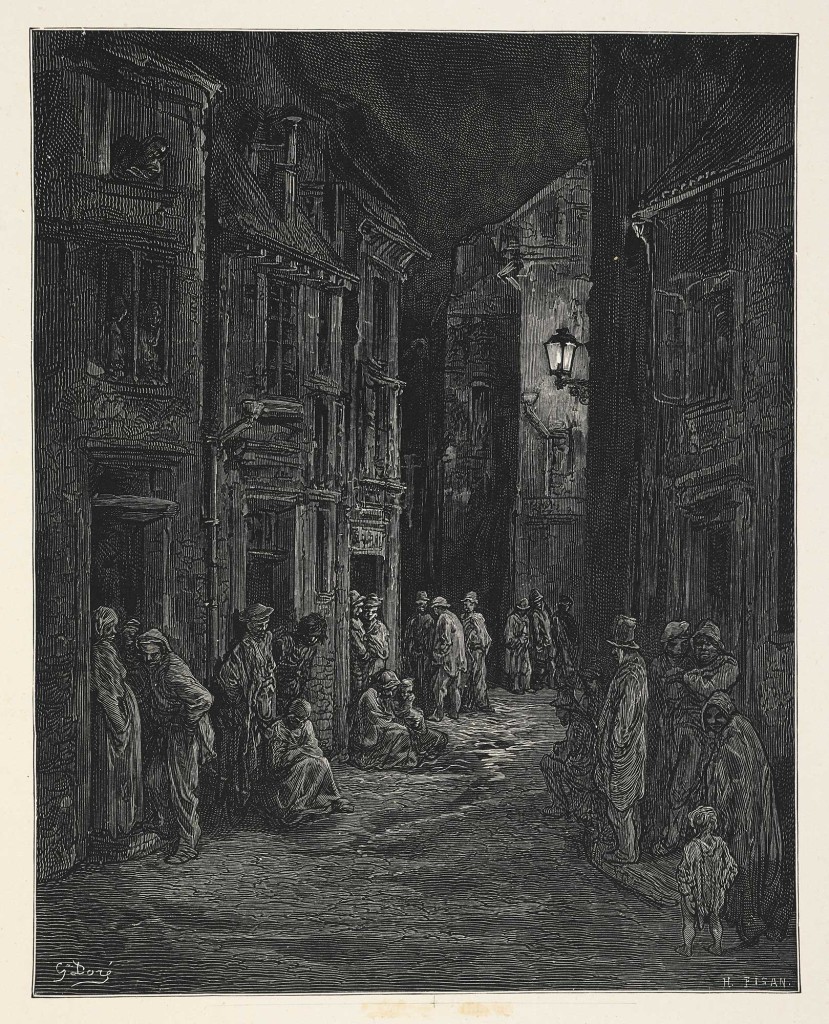

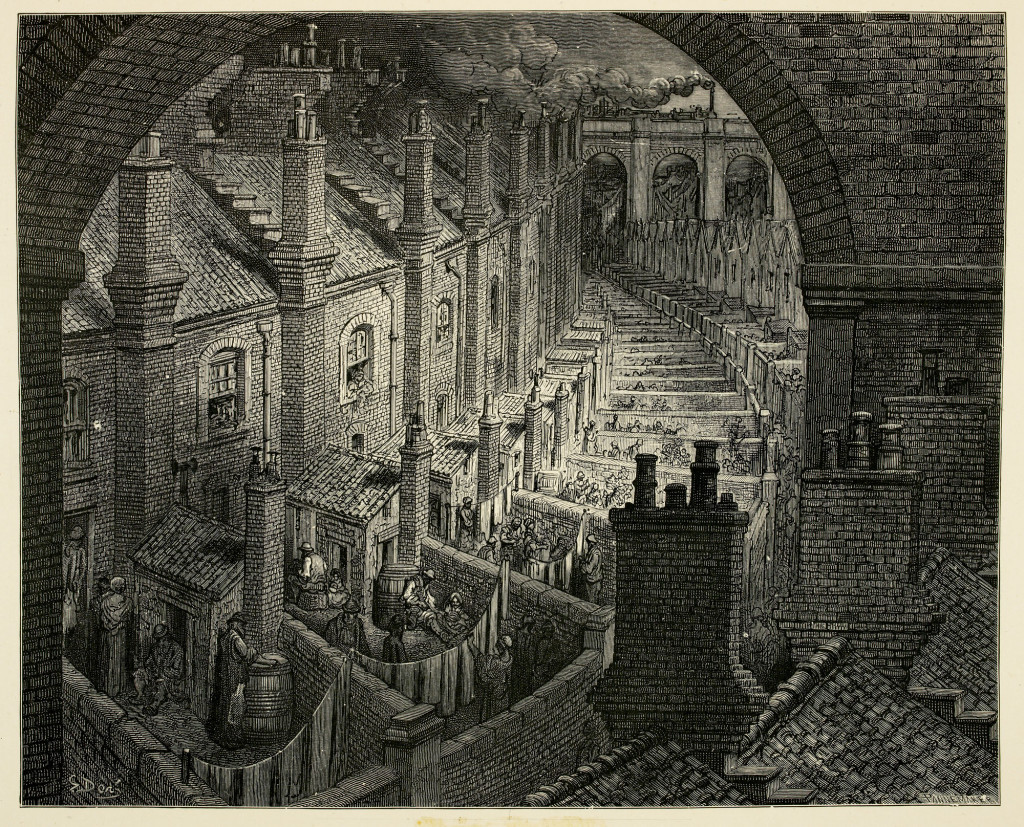

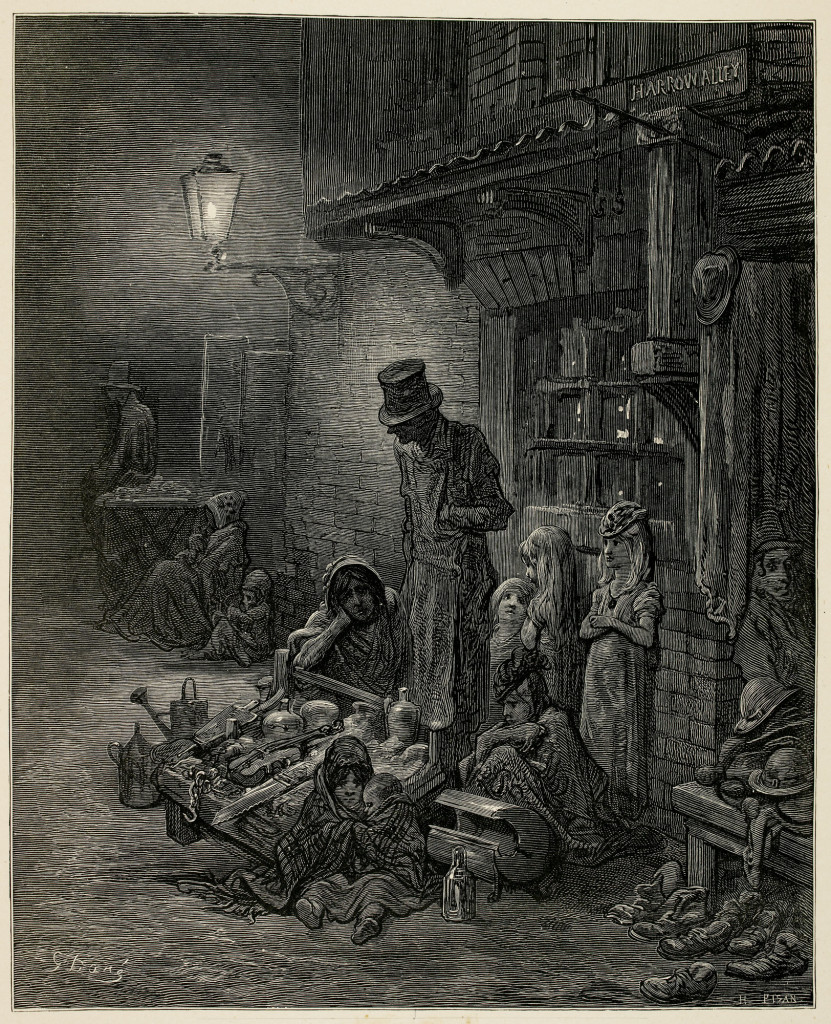

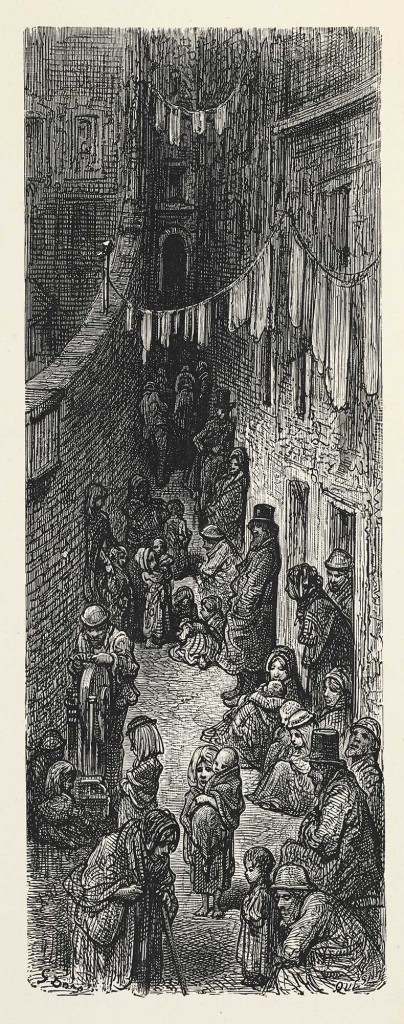

Jo Johnson has a background in punk and techno music and this is her first solo album. It’s quite a departure from her previous work – five slices of ambient sounds and minimalist repetitions. But it’s the attention to detail and the technical accomplishment of these ethereal soundscapes that really appeals. That and track titles like In the Shadow of the Workhouse, which somehow puts me in mind of the opening of George Gissing’s novel The Nether World.

Film Recommendations

Sunset Song – Terence Davies (2015)

Sunset Song – Terence Davies (2015)

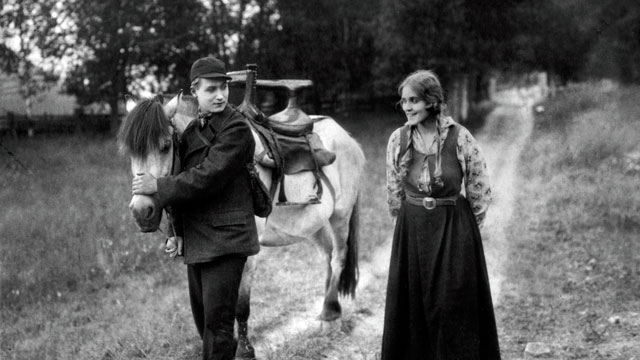

Sunset Song is Terence Davies’s first feature film release in over four years and is based on Lewis Grassic Gibbon’s 1932 book of the same name. Set in a bleak rural community in north-east Scotland on the eve of the First World War, Sunset Song’s connections with Davies’s previous work may not be immediately apparent. However, Davies was clearly drawn to Gibbon’s themes of marital abuse, death and thwarted ambition; personal and universal wounds he had previously picked over in his Trilogy. But there is beauty in this film: Davies’s cinematography is sumptuous, his use of music is inspired and, in Agyness Deyn in the lead role, he has discovered an exciting new talent.

The Falling – Carol Morley (2014)

The Falling – Carol Morley (2014)

The Falling is Carol Morley’s study of friendship, sexuality and mass hysteria at a girls’ school in the 1960s. She creates a satisfying mix of uncomfortable psychological insights and black humour seasoned with a hint of the uncanny.

A Pigeon Sat on a Branch Reflecting on Existence – Roy Andersson (2014)

A Pigeon Sat on a Branch Reflecting on Existence – Roy Andersson (2014)

Roy Andersson’s latest film takes us through a series of episodes of existential pondering. He reaches for truth by deliberately avoiding any hint of superficial reality: his interiors appear to be constructed from balsa-wood, he has a colour palette that is largely restricted to a washed-out shade of green and his actors all wear corpse-like pale makeup. Yet this is a genuinely funny and profound film; rather like Alexei Sayle channelling Samuel Beckett.

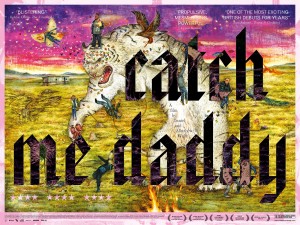

Catch Me Daddy – Daniel Wolfe (2014)

Catch Me Daddy – Daniel Wolfe (2014)

Laila and Aaron are a young couple, one Asian the other white, who seek quiet anonymity in a caravan on the Yorkshire moors. But Laila’s brother has other ideas. The script by Daniel and Matthew Wolfe is acid sharp and Robbie Ryan’s camera evokes a landscape tinged with an eerie beauty.

Like this:

Like Loading...