Several years ago I had a friend, Henk, whom I would meet up with from time to time to ‘drink beer and talk bollocks’, as he put it. For a period of several months he would invariably turn the conversation round to a book he was reading called One Moonlit Night. It was a tale, according to Henk, of myth and madness and was set in a small Welsh slate-mining town around the time of the Great War. He spent a long time reading that book; he had the Penguin dual-language version with the English text on the right-hand page and the original Welsh on the left. Henk, despite his being at least partly of Welsh ancestry, wasn’t a Cymraeg speaker, but he loved the sound of the language and would read the Welsh text out loud just to enjoy the music of the unfamiliar words.

Eventually he gave me his copy of the book and urged me to read it. I still have that copy and have read it several times, though only in English. So far.

One Moonlit Night is a powerful evocation of loss, grief and madness set in a small community. A community that clings to a landscape that is scarred by the workings of the slate industry and a people many of whom are equally damaged. The book is Gothic in its tone and the atmosphere that Prichard evokes. Like that other great example of Gothic expressionism, Mervyn Peake’s Gormenghast trilogy, One Moonlit Night is peopled by a number of grotesque characters with strange names: Will Starch Collar, Bob Milk Cart, Owen the Coal and Humphrey Top House. But underlying all the various human dramas of his book, Prichard depicts something bigger, something much older. The very landscape upon which the village is precariously lodged is always there; it waits and watches.

To think there was a time I didn’t know where Post Lane went after it passed the end of Black Lake. Emyr, Little Owen the Coal’s Big Brother was the first person I remember walking as far as the end of Black Lake, but he didn’t carry on any further cos they found him there on his knees, with his shoes off and his feet all blistered, crying and shouting for his Mam. Huw and me couldn’t understand what was wrong with him, and Moi was only pretending to understand, that’s for sure, or else he would have told us.

The unnamed narrator is a boy who lives with his Mam in a tight-knit community. Their relationship is touchingly warm and loving, and is apparently based on Prichard’s memories of his own mother. The boy has two close friends, Huw and Moi. Together the boys come to learn about sex, death and madness. The tone is bleak, but not without humour. The narrator, despite the hardships he experiences, is uncomplaining and accepting. Indeed, the overall effect of the story of his childhood is life-affirming; Prichard shows us through his protagonist that he loves life because it is so precarious.

But one character, deep and brooding, remains in my memory longer than all of the others. Black Lake, just outside the village and as ancient as the hills in which it nestles seems to act as a repository of all the joys and sorrows, generation upon generation, that have been enacted upon the local landscape. And, at the conclusion of Prichard’s beguiling tale, the lake’s black waters act as a mirror to reflect the cruel light of the moon.

Jees, the old lake looks good too. It’s strange that they call it Black Lake cos I can see the sky in it. Blue Lake would be a better name for it, cos it looks as though it’s full of blue eyes. Blue eyes laughing at me. Blue eyes laughing at me. Blue eyes laughing

| Caradog Prichard: A Brief Biography

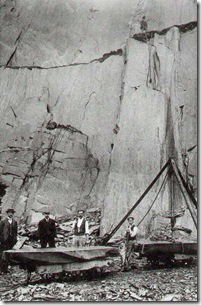

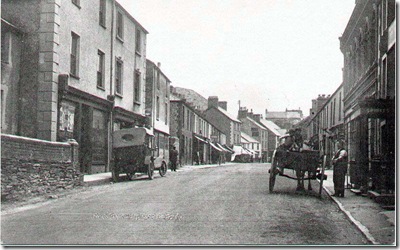

Caradog Prichard was born in 1904 in the Welsh slate-quarrying town of Bethesda. He worked on a number of Welsh local newspapers before moving to London where he became a sub-editor on the Daily Telegraph’s foreign desk. His published works include three collections of poetry and a semi-fictional autobiography. One Moonlit Night is his only published novel and, though first published in Welsh, it has since been translated into English and seven other languages. Caradog Prichard died in 1980. |

Your description reminds me of this artwork:

Dark pool – by Janet Cardiff and George Miller:

http://www.cardiffmiller.com/artworks/inst/darkpool.html

Yes, I see that. When the Black Lake speaks at the end of the book she tells us: ‘I am learned in the chemistry of tears; I assembled them in the cauldron of the centuries, then dissected and reduced them to their elements.’ I wish I’d included that quote in the blog post!