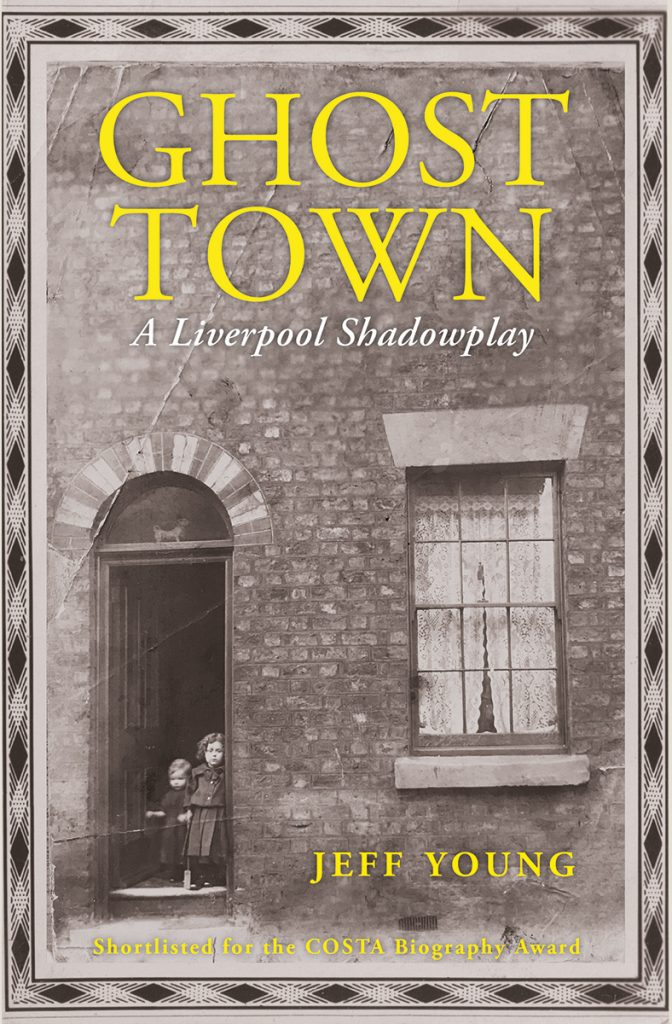

Book Review – December 2021

I go to the pubs where Allen Ginsberg drank with Adrian Henri in May 1965 when he declared Liverpool to be ‘at the present moment, the centre of consciousness of the human universe’. I walk past the building on Hardman Street where Atticus Books relocated, and where William Burroughs signed copies of his novels in 1982. I see Bob Dylan in 1966, hanging out with street kids in the doorway of a derelict warehouse on Dublin Street. I glimpse Arthur Rimbaud, wandering through the city in 1876, on his way from Cork to Le Havre after absconding from the Dutch Army.

I feel an affinity with Jeff Young’s Ghost Town: A Liverpool Shadowplay. My mother was from Liverpool, one of six sisters from Walton. This meant that, as a child, although I lived elsewhere, I frequently visited Liverpool and felt part of a ready-made clan of Scouse aunts, uncles and cousins. So, like Young, the Liverpool of the 1960s haunts my memories of childhood and the city of the 1970s still stalks my teenage recollections.

Young’s Liverpool is a city populated by ghosts. He evokes people, buildings and whole streets that are long gone but which still exist in shadow form. Liverpool is a radically different city from that of the 1970s, but its ghosts still inform the city’s character. I recall Niall Griffiths, the Liverpool/Welsh writer, saying that, to understand Liverpool, you have to remember that it is a Celtic city and that its unique blend of exuberance and melancholy comes from the twin Irish and Welsh influence. With Ghost Town Young succeeds in capturing this mood: he laments the Liverpool that has been lost, but at the same time celebrates its memory and the legacy it has left us.

Young’s first home was in inner-city Liverpool, near to the Everton FC football ground. His grandparents and other members of his extended family lived all around. Then, while he was still a child, the family moved to a house on a new estate on the outskirts of the city. Young’s new home had a bathroom, he had his own bedroom and in this rural demi-paradise the fields, woods and canal were his playground. Meanwhile the old centre of Liverpool was fast disappearing: much of what the Luftwaffe had failed to destroy was demolished by the city planners in the 1960s.

Young’s first home was in inner-city Liverpool, near to the Everton FC football ground. His grandparents and other members of his extended family lived all around. Then, while he was still a child, the family moved to a house on a new estate on the outskirts of the city. Young’s new home had a bathroom, he had his own bedroom and in this rural demi-paradise the fields, woods and canal were his playground. Meanwhile the old centre of Liverpool was fast disappearing: much of what the Luftwaffe had failed to destroy was demolished by the city planners in the 1960s.

School in Young’s Liverpool suburb failed to engage him and he seemed destined for a dead-end factory or office job. Having discovered Barry Hines’s A Kestrel for a Knave, he found himself increasingly identifying with the book’s protagonist, Billy Casper. Few of Young’s teachers took any interest in him or offered encouragement, but:

The only good teacher I ever had was an art teacher who wore a kipper tie and found two treasures in a gutter. The first was a rain-soaked record, John Coltrane’s A Love Supreme, which he played us one day in art class…. while the art teacher read to us from his second gutter treasure: a paperback copy of Franz Kafka’s Metamorphosis.

Discovering Kafka was an important step in Young’s own metamorphosis into becoming a writer. He left school with few qualifications and ended up in a stultifyingly tedious job as a filing-clerk with the local council. Lonely and directionless, the teenage Young drew solace from art, music and fiction. He found comfort and inspiration in the works of outsider artists such as William Burroughs, Mark E Smith, David Bowie, Alan Garner and the films of Terence Davies; works that intersperse melancholy, longing, a sense of loss and occasional joy.

Young found himself drawn back to the streets of the city in which he was born. He would sit alone in pubs like The Vines and Yates’s Wine Lodge, drinking, smoking and reading his latest paperback. Liverpool was the place he went to see bands, buy records, pick up art materials and mooch around the second-hand bookshops. The musty old paperbacks he picked up for a few pennies were Young’s education and his escape. More than anything, however, Liverpool was the place where he walked and looked, imprinting the city’s streets and buildings deep into his psyche.

It was Young’s mother who encouraged his love of Liverpool and its buildings; finding out what lies behind a building’s anonymous façade, discovering the history that is mapped out in the city’s streets. As a child, a trip into town with his mother would involve frequent diversions into alleyways, through doorways and up staircases. Her habit of ‘having a nose’, as she put it, was something which stayed with Young for life. He become the outsider constantly looking in, but at the same time developed into someone who was deeply embedded within the city he loved and to which he belonged.

The great achievement of Ghost Town is the way Young weaves in his own story and that of his family with the story of Liverpool. Personal memories, folk memories and dreams merge together; the streetscape of the old city is, in Young’s mind, superimposed upon that of modern Liverpool. In the shadows the city of the sixties, seventies and earlier still exists.

Ghost Town is not just something written by Jeff Young; it is, in the truest sense, part of him. He and his ghosts inhabit every page. Open it up and smell the diesel fumes from a Crosville bus, hear the lowing of ships’ horns on the Mersey, taste the bitterness Higson’s ale and run your fingers over the yellowing coarseness of the pages of a second-hand paperback from the comic shop on Moorfields. In Ghost Town we are shown Liverpool through Young’s eyes while he, in turn, looks at it it through the vision of those who came before him:

My mother taught me Liverpool; she was the guide into its shadows, into the hidden and forgotten. When I walk through Liverpool, and when I write and talk about it, I summon up my mother and try to see it through her eyes. I have used my blind grandfather in the same way, have tried to see the city through his blindness, to try to feel what he must have felt when the city he knew was being demolished.

Jeff Young

Jeff Young is a writer for theatre, radio and screen whose TV credits include Eastenders, Holby City, CBBC and Casualty. He broadcasts essays for Radio 3, collaborates with artists and musicians on sound art installations and has worked on many arts projects in Liverpool and elsewhere, including a residency in Bill Drummond’s Curfew Tower. He is a senior lecturer in Creative Writing at the Screen School of Liverpool John Moores University.

Pingback: Wild Twin by Jeff Young | Psychogeographic Review

Pingback: Psychogeographic Review’s Books of the Year, 2024 | Psychogeographic Review