Cléo From 5 to 7 is one of the key films of the French New Wave. Director Agnès Varda sets out to create a cinematic odyssey about our perception of time, with much of the action filmed in real time in the streets of Paris.

Cléo, Varda’s central character, is presented as a woman who is running out of time. The camera follows her for ninety minutes as she travels through the Left Bank, killing time while she awaits the results of some very grave medical tests. All around her are reminders of death – snatches of radio news broadcasts about the Algerian war, African death masks glimpsed in a shop window; but there are also confirmations of life, particularly in her encounters with her friend Angèle and Antoine, a young soldier on leave from Algeria.

At several levels, this is a film set in time. Varda captures the Paris of the early 1960s with the accuracy and precision of a documentary-maker. Cléo’s journey can be plotted on a map of Paris not just to confirm the reality of her route, but to reveal the accuracy of the film’s timings. But although Cléo’s journey takes place in ‘real’ time, Varda also plays with the way both we as the audience and Cléo as her protagonist experience that time.

Time seems to expand and contract with Cléo’s emotional state; there is no ticking clock underlying the soundtrack but, as the time of Cléo’s fateful appointment approaches, we nonetheless become almost viscerally aware of each second ebbing away at an ever-quickening pace. Varda seems to be suggesting, time is fluid and our perception of it is subjective. Whilst much of what we see in Cléo From 5 to 7 is hyper-real and shot in crisp mono-chrome, in allowing us to step inside Cléo’s skin for 90 minutes we become aware of a reality that exists beyond that which we see on the everyday surface and a concept of time that goes beyond the here and now.

Cléo From 5 to 7 is presented in 13 chapters, each assigned with the name of one of the film’s characters. The number 13 is significant in many religions and in folklore throughout the world; it is also the traditional number of turns in the hangman’s knot, an oblique reference back to the tarot reading in the opening sequence. To break down Cléo’s journey into a numbered sequence also creates echoes of a spiritual journey, such as that of the Via Crucis and Dante’s Inferno.

In Varda’s Paris the traditional is covered with a thin layer of the modern. Cléo is a pop singer and minor celebrity, seemingly at the cutting edge of vibrant 1960s modernity, but she is at the same time locked into a reliance on superstitious beliefs; in fact, the first time we see her is at a tarot reading.

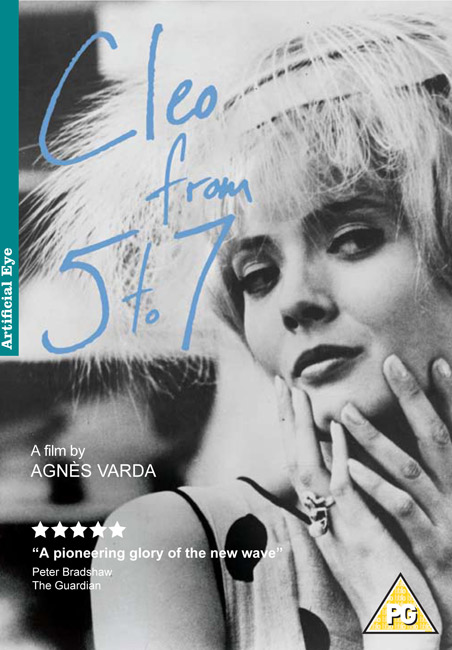

Cléo is played by the achingly beautiful Corinne Marchand. Marchand captures perfectly the self-dramatising, but ultimately vacuous, nature of the character she inhabits. But, by the end of the film, Cléo’s odyssey leads us to a place which hints at something universal, something redemptive that lies beyond her frail humanity.

Varda plays with the audience’s perceptions; alongside her film’s grounding in reality – real locations and real time action – she allows the art of the film-maker, the illusion creator, to show through. Thus, for instance, we move suddenly from the lush colour of the opening tarot reading sequence to mono-chrome of the rest of the film.

Like a butterfly trapped in a jar, Cléo flits from one friend to another and from one habitual location to yet another: café, hat shop, artist’s studio, cinema. All the time wrestling to come to terms, perhaps for the first time ever, with her own mortality. She gives away to a friend the hat she spent so much time choosing earlier and removes her elaborate wig, as if to embrace some kind of transformation.

In Parc Montsouris she meets Antoine, a sensitive and attentive young man who is also facing death; later that evening he will join his regiment to be shipped to Algeria. Antoine discourages her from merely ringing the hospital and suggests she needs to see her doctor, and by implication meet her fate, face to face. He offers to accompany her and they set off for Hôpital de la Salpetriere.

Image of DVD cover courtesy of Artificial Eye Film Company Ltd