I have to confess a personal interest in East of England: having enjoyed Eamonn Griffin’s work on Twitter for quite a while, I was one those who helped crowdfund this novel. I’m pleased to say that I am not disappointed.

I have to confess a personal interest in East of England: having enjoyed Eamonn Griffin’s work on Twitter for quite a while, I was one those who helped crowdfund this novel. I’m pleased to say that I am not disappointed.

The central character is Dan Matlock, a career debt-collector and enforcer. As the book opens Matlock has just been released from prison having served a sentence for manslaughter. The complication is that the person he killed was a member of the local organised crime family, the Mintons. They stayed their hand from exacting their revenge while Matlock was in prison; but surely, he reasons, it is only a matter of time before they act. Matlock has a choice: run to safety and establish a new identity somewhere, or return to his former haunts and await whatever may come.

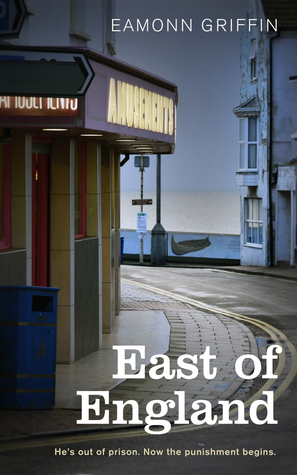

Matlock’s turf is that narrow strip of his home county nestled between the Lincolnshire Wolds and the coast. The territory is bisected by the A16, which runs from Grimsby in the north to Boston in the south. Much of the action of East of England takes place on or alongside this road, indeed it is as much a character within the world Griffin creates as Matlock himself.

This is a land of caravan parks, amusement arcades, agri-industrial units and greasy-spoon cafes. But even in these shabby towns that have clearly seen better days, there is money to be made, and the Mintons have most of the angles covered. The pages of this book are splattered with violence: bloody, shocking violence. Griffin does not judge or condemn, he merely presents us with acts of savagery to respond to as we will. The writer this most reminds me of is Derek Raymond and his Factory series of novels.

East of England is a work in the tradition of English realism and never strays into any form of literary experimentation or deep psychological explorations of its characters. However, it does have a gripping narrative pace and energy, and a strong evocation of life in provincial England. Something Griffin does which I find slightly disconcerting is to change the names of real places to a recognisable approximation of the original. Thus, Skegness becomes Skegthorpe, Louth is Loweth and Mablethorpe is renamed Mableton-on-Sea. Other than an homage to Thomas Hardy, I’m not quite sure what this achieves.

Griffin is from this part of Lincolnshire, although he now lives in North Wales. East of England was written, apparently, in his local café in Llangollen. This perhaps goes to explain why so much of the action in the book is punctuated by Matlock’s eating and drinking.

I hear talk of this being the first book in a series; indeed a taster for the next book is offered up at the end of this one. It is a sequel I will read with interest.

Eamonn Griffin, East of England (London, Unbound, 2019)