I have to confess that when I first heard that Gareth Rees was moving from his home in East London to the Sussex coastal resort of Hastings it seemed to me odd for a relatively young writer to be forsaking the vibrant metropolitan cultural hub in order to settle in a quiet provincial backwater. Particularly so when Rees had just spent several years developing Hackney Marshes and the River Lea as his personal genius loci and the setting for his first novel, Marshland. However, while Hastings is very much part of England’s provincial outlands, one thing we learn from The Stone Tide is that it is a decidedly unquiet place.

The Hastings of this, Gareth Rees’s second book, is haunted by ghosts: emanations of the town’s past, present and, indeed, its precognitive future. Perhaps this is hardly surprising given that Aleister Crowley, the so-called Great Beast, spent his final days in Hastings and ever since the place has attracted a variety of mystics, occultists, visionaries and shysters. But Rees is also haunted by the ghosts that he brings with him, memories and presences that take root and grow in the fertile loam of Hastings’ psychic vortex.

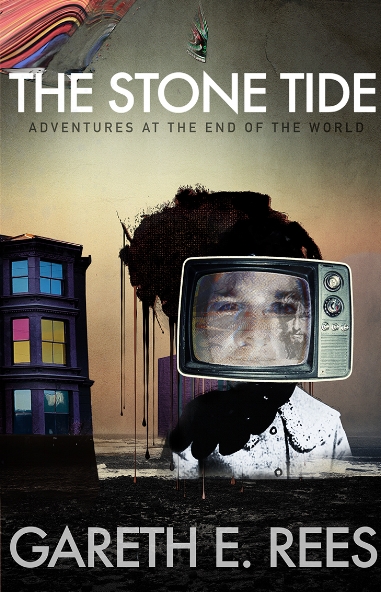

The Stone Tide is peopled with a cast of strange and compelling characters, past and present. Charles Dawson of the infamous Piltdown Man hoax rubs shoulders with Sir Arthur Conan Doyle and Teilhard de Chardin, the Jesuit priest who predicted the World Wide Web. Robert Tressell, one-time Hastings resident and author of the Ragged Trousered Philanthropists gets a mention, as does Rod Hull and Emu. John Logie Baird lived here for a time, arriving in 1923 to recover from a period of ill health. Whilst in the town he continued to experiment with the transmission of moving images. There is little evidence that Baird and Aleister Crowley ever met, but in Gareth Rees’s alternative history they do. Crowley confronts Baird on Hastings seafront accusing him of stealing his transmission idea, corrupting it from a medium to accumulate and raise human consciousness to another level into a device for mere entertainment:

Unbeknown to you, this technology was being developed in secret by adepts, like Promethean fire, for the liberation of mankind….if only your greedy little mind could imagine such a thing – to see across dimensions, to commune with the spirits, to wield influence in the universe!

The Stone Tide starts off in conventional enough fashion. Burdened by debts Rees, his wife Emily and their two young daughters move from London to a large, end-of-terrace Victorian house on the south coast. The house has potential but is badly in need of renovation, so the couple have the idea of gradually doing it up into their idyllic family home at the same time as Emily pursues her burgeoning career in digital marketing and Rees works on his second novel.

In a parallel universe this book could be the simple tale of a shiny, happy couple transforming a wreck of an old house into their shiny, happy new home: the dross of dereliction transmuted into designer chic, no doubt with numerous asides about local characters and colour. But from their first evening in Hastings we realise this is not going to be the case. It is even more run down and unloved than they remember it from their first viewing:

Above the front door, a cracked stone lintel was the house’s broken heart. Its subsiding interior had the wonk of an eighteenth-century galleon. There was an oppressive gravity to the place, as if it could no longer bear the weight of its own existence.

The house is peopled with odd noises and distant voices. It seems to be alive with creatures revelling in its decay: swarms of flies and rats and one particularly evil-seeming herring gull. Everywhere there is dust: the accumulated residue of decades, a shedding of generations of human skin. They clean up one lot of dust and more appears by the next day.

I enjoyed Marshland, Gareth Rees’s previous book, but this is something entirely different. Whereas his earlier novel sat comfortably in the oeuvre of London psychogeographic writing that has become so ubiquitous in the last decade or so, The Stone Tide, although clearly from the same writer, is instead a work of breathtaking originality. If Marshland was Gareth Rees’s With the Beatles novel, then The Stone Tide is definitely his Rubber Soul project. In other words, he has progressed from the competently entertaining to something strikingly new and exciting. I look forward to his Sergeant Pepper moment in the not too distant future.

Nothing is solid in The Stone Tide: everything is permeable and subject to the ravages of time and nature. Rees’s grip on reality begins to falter, his marriage shows cracks and their new home continues to crumble and decay. Even the very rock upon which Hastings is built proves to be neither solid nor permanent; the actions of tide and river cause whole chunks to fall into the sea. Indeed, the sea is ever present; it is vast, brooding and threatening and is a constant reminder to Rees that it was beside this same sea, in another part of this island, that his best friend died two decades earlier.

The only place to go was the sea. The indifferent, angry, calm, fucked-up sea. The sea that began life on earth. The sea that would finish us all off. The sea that took Mike then brought him back again.

But it is not just the crumbling cliffs of Hastings where a rift is opened up, the linear flow of time itself seems to have been disturbed. When he arrives in Hastings Gareth Rees seems to be secure on the rock upon which his life is built: his sense of himself, his marriage, family and his career, all of which seem to be going well. Even the greatest sadness of his life, the tragic loss of his best friend, Mike, some twenty years before, seems to be something that Rees has now dealt with, something with which he has come to terms. But in Hastings he assailed by forces which open-up the crusted wound of his grief.

Rees writes with painful honesty:

Our family was falling apart and I had failed to see it. I’d let it happen. I’d walked away from the truth.

There is much sorrow in this book, but its overall effect is not entirely bleak or self-indulgent; the sadness at the heart of The Stone Tide is leavened by the verve of Rees’s prose and his self-deprecating humour. Amid the despair and aching loss in this book there is hope and a determination to carry on:

Humankind is not locked into some ordained destiny. Consciousness is a force as powerful as time, strong as gravity. It moves through the universe, through the earth, through animals, vegetation and rocks. It mutates and evolves. It creates its own reality. The human mind, with its extraordinary imagination and capacity for invention, has unlimited potential, both to create catastrophe and avert it.

Rees worries throughout the time covered by this book if he will ever complete his current writing project and, if he does, whether it will be any good. Clearly, he does finish it and, equally clearly, it is indeed very good.

The Stone Tide: Adventures at the End of the World is available to pre-order from the publishers, Influx Press