…the darkness does not lift but becomes yet heavier as I think how little we can hold in mind, how everything is constantly lapsing into oblivion with every extinguished life, how the world is, as it were, draining itself, in that the history of countless places and objects which themselves have no power or memory is never heard, never described or passed on.

W.G. Sebald, Austerlitz

There is nothing like unemployment for educating oneself

A.L . Lloyd

Jointly Presented by Travin Systems and the Pyschogeographic Review

Rock Park words by Charles Swain Photography by Bobby Seal Fort Wetherill words by Bobby Seal Photography by Charles Swain Design By Charles Swain at The Travin Press

A Psychogeographic Collaboration

This project came about as a result of a growing mutual appreciation of the other’s work by Charles Swain, Head Honcho at Travin Record Systems, and Bobby Seal, copywriting gun for hire and psychogeographer-in-chief at Psychogeographic Review. Although originally from the UK, Charles is currently based in Baltimore and Bobby lives on the Welsh borders. It seemed natural, then, that the project should embrace this geographical disconnect and come up with an idea that spans two continents.

Our Starting Point

We agreed to exchange six to ten photographs of a place we thought was interesting; somewhere that, to mangle Emily Dickinson’s phrase, dwelt in possibility. Other than the pictures, we agreed to disclose only the barest facts to each other about our chosen location. We would then each produce a creative response to the pictures: it could be prose, poetry, music – anything. But we could only work from the pictures, not with any further research on the location.

Bobby Seal: The place I chose for Charlie is Rock Park, a rundown Victorian suburb in Rock Ferry, near Birkenhead. I chose Rock Park because I’ve often passed by, but never explored it. Its main fascination for me was that it was the birthplace of May Sinclair, a writer for whom I have a great admiration.

Rock Park was built on the banks of the Mersey between 1837 and 1850. The large, substantial houses were constructed with local sandstone and housed wealthy merchants and brokers who traded across the river in Liverpool. Until 1939 there was a ferry to Liverpool.

Rock Park has declined in recent decades: the wealthy have moved away and many of the houses have been divided into flats. In the 1960s a new by-pass cut a swathe through Rock Park and many of the houses were demolished. I didn’t find May Sinclair’s house, but I did find the house once lived in by Nathaniel Hawthorne, the American writer. He was US Consul in Liverpool for a time and lived at Hawthorne House, 26 Rock Park. Unfortunately, all that is left is one gate-post.

Charles Swain: When we came up with the initial concept for the project I had a number of places that I had previously visited that I could have chosen to present to Bob. The setting had to be in the USA, so that ruled out a lot of locations from back home in the UK. I was originally going to write a piece on Fort Wetherill myself for Travin Systems but it struck me as having the potential to work really well in this project.

Why This Collaboration, or What the Fuck Were You Thinking Of?

We’d both agreed a while ago that it would be a good idea to work on some kind of collaboration, but the basic idea for this particular project came from Charlie. Although we’re working in different fields, there seems to be some commonality in the themes we each explore: place, history, memory, the stories wrapped up within a landscape.

The project came about through thinking of alternate ways to present places. Places that are a wellspring of emotion and curiosity via the depth of their history, their physical appearance and the singular atmosphere that is present when visiting them at a certain moment in time. This multiplication of variation sifts through your emotional state at the time to create an impression and that is what I try to put down via words, photography or music. We are both extremely interested in these ideas and to allow each other to interoperate each’s visits seemed natural. It was also thoroughly enjoyable.

Practically speaking it made sense to accept that I am based in the UK and Charlie in the US, so any collaboration would of necessity be predicated on an electronic dialogue. But actually, that’s what gives the project its cutting edge; we chose delib- erately to restrict ourselves to writing about a landscape we had never visited using as inspiration just the handful of photo- graphs provided by the other person. In other words, we would each try to create a new reality from, to use Eliot’s words, nothing more than ‘a heap of broken images’.

By presenting someone just photos and a brief outline of the location, which is what we did in this piece, you effectively ab- stract them in two ways. From the physical location itself and your own or others’ impressions of that place. Then you ask them to mentally transcend the 3000 miles or so to write about it.

In restricting what one’s collaborator sees to a handful of pictures, one’s imagination is freed to go beyond the confines of the lens. The human brain has a unique talent for constructing images and patterns, even where none exist in an objective sense. This is the story of a half-blind stumbling towards discovering some kind of meaning from a set of photographs.

This is What We Thought

I’ve never explored the east coast of the USA, though I have a vague idea of the location of Rhode Island. From the sparse factual details provided, I was aware that Fort Wetherill had been a military strongpoint since colonial times and was last used during the Second World War. Having been abandoned for many years, it was adopted as a State Park in 1972. We had already agreed that we would do no further research on the location in the pictures provided by the other. Sorry Wikipedia!

The first thing that struck when I saw the Rock Park pictures was the houses. I have lived in a house similar to some of those pictured, back in Matlock. With their elegiac gardens and surroundings held in a kind of semi-status. That and those books stacked against that bay window.

Charlie’s pictures are redolent to me of a place built up out of layers laid down over several centuries of history. A place haunted by ghosts; a landscape of echoes and shadows. Concrete and rock. Litter and graffiti. Yesterday and today.

I actually stumbled across the place on a short visit to Rhode Island towards the end of winter. To go into my own thoughts on the place would be at odds with this project but I do remember a relative of mine hauling himself onto the vast concrete fields that make up the roof a week or so before a scheduled hip replacement.

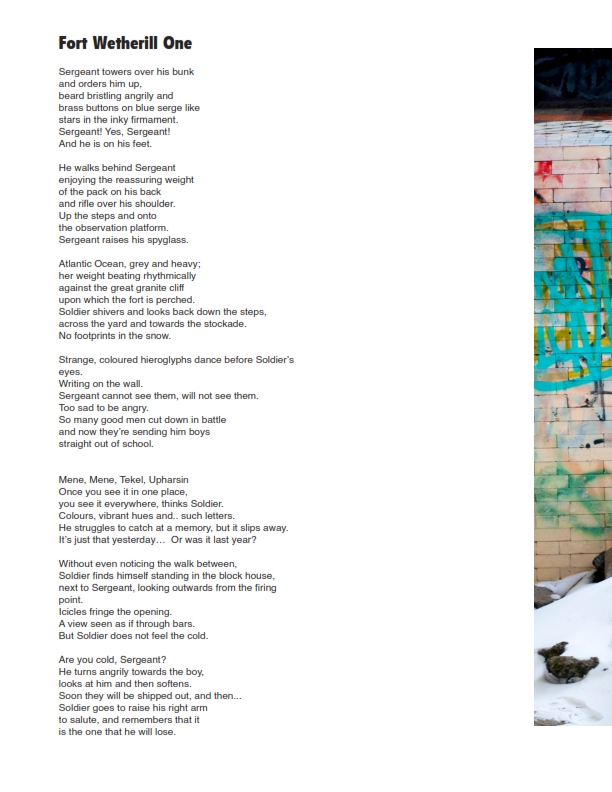

I kept thinking about the fort, seeing beyond the present-day beer cans and graffiti. Perhaps this place was a garrison in the American Civil War, guarding the Union shipping lanes from Confederate marauders. Or maybe a staging post from where soldiers were shipped out to join the battles further south. Thousands of men and boys sent into the slaughter. Cannon fodder. As I contemplated Charlie’s pictures, it seemed to me that poem was the best way to express my thoughts; to conjure up the odd tale that insinuated its way into my mind, a kind of ghost story in reverse.

I wanted to do something a little different than the usual essay format that I usually present. I like the idea of” fiction” with a firm basis in a realistic rendering of a place-be it objective or subjective. But also to capture those transient wisps of thought. One’s psychological reaction. In a lot of my prose I am trying to conjure and evoke a very tangible impression of the physical shrouded in the incorporeality of the supernatural or the bizarre. Building an image that you can sort of leap into but still be a little wary. So a film script (or any script or screenplay) really gives you the means to add yet another layer of visual direction.

A story formed in my head of a couple of soldiers from the American Civil War who were stationed at the fort, a young conscript and an old drill sergeant. They continue to patrol the fort unaware, or perhaps reluctant to accept, that the war ended a long time ago and that their corporeal selves died in the conflict. They exist in this location in one of many layers of ‘then’ which are all overlaid by a ‘now’.

My first thought was a short story, but I soon dropped that idea and wrote a narrative poem: Fort Wetherill 1. Dissatisfied with that, I wrote Fort Wetherill 2. This is shorter, less wordy, more condensed, but with an attempt to give a greater density of meaning to each word, phrase and space. I’ve also reverted to making the fort the main character – the entity that remains in situ while humans, and even their ghosts, come and go.

Am I satisfied with my second effort? No, but then I’m never completely satisfied with any poem I’ve ever written. As Paul Valéry said: ‘a poem is never finished, only abandoned.’

Rock Park by

Charles Swain

Final Shooting Script

1. Ext. Day

The scene opens on a backdrop of thick, heavy ,intertwined verdure bright leaden curtain of foliage draped over a gnarled wooden framework.

In the foreground stands a pillar of dull ivory stone with a name carved in relief near its top. From behind this the shape of a man appears-his outline becoming more defined as he steps out from the cool recesses of the living curtain. He wears mourning dress, a stiff collar and a bright gold watch chain. At first we see hem only in silhouette but as he steps into the light his features become clear, vivid intelligent eyes, an aquiline nose and full, slightly parted lips. His hair is longish and parted to one side.

We follow him as he starts along a curving, unmarked road of grey tarmac. Along one side are low privet hedges broken occasionally by tall Iron gates. Some of these gates have swung heavily to one side, their hinges rusty and stiff. The man enters through a particularly ornate set but hesitates on the threshold of the property as if their openness belies a malevolent intent. Shrugging he moves up the spacious drive. He kicks bits of masonry into the prolific tangle of undergrowth that has replaced the front lawn.

Going up to the door of the large house he pulls a large key from him pocket and tries it in the lock. The door does not yield so he pushes his shoulder against it while turning the heavy knob.

[Camera zooms out to a long shot encompassing the man and the house from the open gate]

He takes a step back from the door and raps sharply one the door with the heavy black knocker. A ships horn blares from some distance away and a pair of cats scramble through a hole in a nearby fence.

[Camera zooms in tight over man’s shoulder]

As he turns away from the door and walks around the corner of the house descending some stone steps that lead to the back.

2. Ext. Day

Scene opens on a wide shot of mud flats. In the mid-ground there is a strip of grey water punctuated here and there by small boats and the occasional neon buoy. In the background a cityscape stretches, uniform in its dirty, dull shades of black, brown and grey. There are low sheds, church spires and the outlines of various masts and cranes. Above this the sky fills out the view as you would fill a jar containing some soft metal with oil. Right in the center of the frame, in the middle of the muddy beach stands the man, the wind whipping at the tails of his coat and around his trouser cuffs.

[Close up of the man’s face]

His skin looks pallid and slightly greasy. His bright green eye seeks restlessly along the horizon. We see a faint reflection of a cathedral spire in the lens.

[Cut to a shot of the man and the beach from one of the boats]

The man bends and pulls something out of the mud. It’s a small volume containing only one leaf.

[Cut to page in man’s hands-text is readable]

“The neighborhood was a grand one and that made its fall into dilapidation quicker and its impact felt more keenly decay of ash and ivy, of dimly lit interiors glimpsed through bay windows. A decay of rotted books by forgotten brooks their pages spread open into the soil”

The man slides the book back into an inside pocket and we follow him as he walks quickly back up some steps.

3. Ext. Day

Scene opens with medium shot of what appear to the back entrances to a row of large Victorian houses. At some points there are sections of wrought iron railings, slightly less grand than their counterparts at the front. There are stone pillars and the dappled grey- white of modern lampposts. Some of the entrances are boarded up with chipboard and cheap planks. A thick cable of ivy runs down the center of one of these shuttled portals, its leaves are of a dark racing green and they give of a rich, bitter scent. The man is centered with his back to the camera, his arms stretched above his head and his hands flat against the wooden boards.

[From the POV of the man looking down]

He notices a chink in the makeshift timber armor of the door in front of him. Through it can be seen a heart shaped gate handle of black iron. He pulls and twists it. The planks first creak and then begin to tear away from the nails and blue twine that secure them.

[Shot pans 180 and presents a wide-angle of the man emerging onto a pedestrian overpass strung above a busy road]

On one side of the road, just visible is a bank of grass boarded by thick trees. On the other tower the tall red brick houses of Rock Park, there gardens terminating at a sheer wall that drops of into the busy channel below.

The man walks along to the middle of the bridge and stops to lean against the railing. He gazes up the road flinching slightly as large wagons and fast moving cars speed underneath him.

[Cut to close up of the man’s hands gripping the railing]

We notice that the surface of the rail has been carved with names , initials and symbols. As he lifts his hand a tiny block of neat text is reveled, scratched into the flaking steel. He pulls a leaf of blank paper from his jacket pocket and a slim stick of graphite from his boot. He quickly makes a rubbing of the words and holds the paper up to the watery sun.

“The dual carriageway split the houses from their companions and disembodied their gardens from the mother fields and meadows. Feet crackle on broken brake light at the foot of the ribbed concrete face. You can throw a lucozade bottle through the sky light and have it thud heavily onto the bonnet of a rover 25 or puncture itself on a cargo of rubble and coat the powdery stone in a sticky orange. Drivers looking at the dismal edifices in the half-light of a cloud blanketed evening see marble figurines strangled by vegetation. Ornate formality gone to seed under the glow of innumerable sodium lights. Thin sheets of life laid over one another like wrinkled tracing paper.”

Download the PDF version of this collaborative project report here:

Great stuff – Interesting project guys.

Thanks, praise indeed, I tend to think of Fife Psychogeography as the benchmark in our genre!