The Jago is not only a geographical area but an existential state of desperation

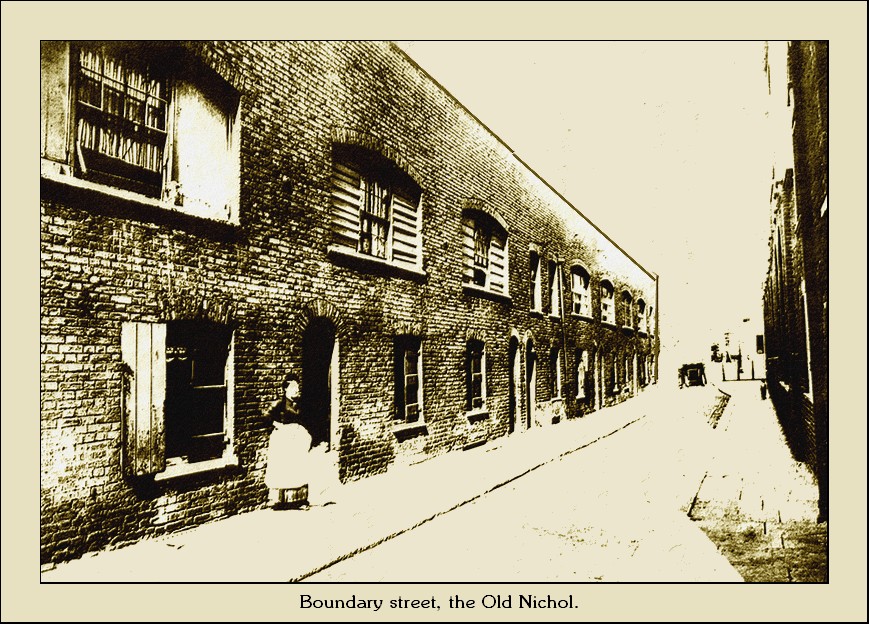

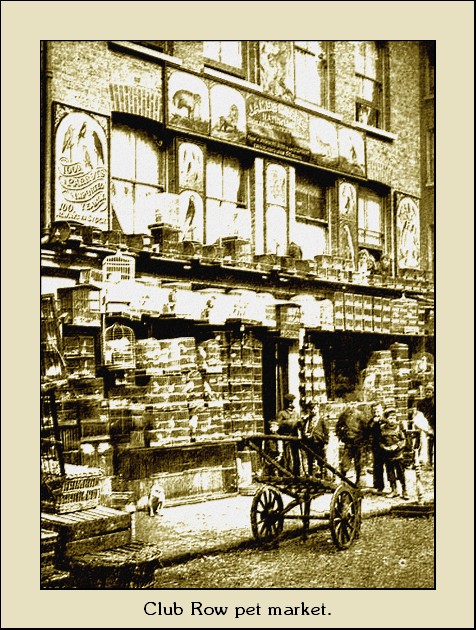

A Child of the Jago is London-born journalist Arthur Morrison’s best known novel. It was first published in November 1896 and is set in a fictional East End slum known as the Jago, which Morrison based a real district called the Old Nichol. The Old Nichol was a rookery of squalid dwellings squeezed into a slice of land between Shoreditch High Street and Bethnal Green Road in London’s East End. It was demolished in the mid-1890s and replaced by London’s first experiment with council housing, the Boundary Estate.

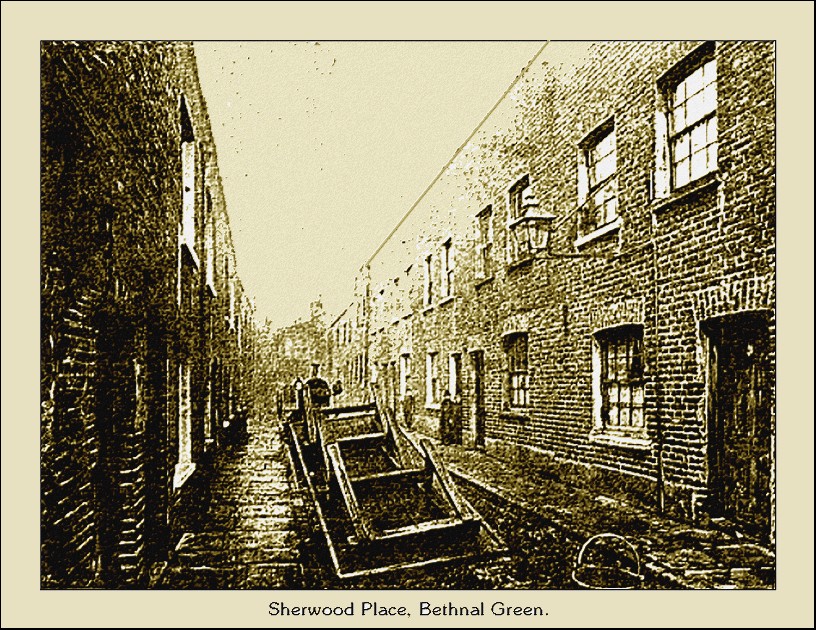

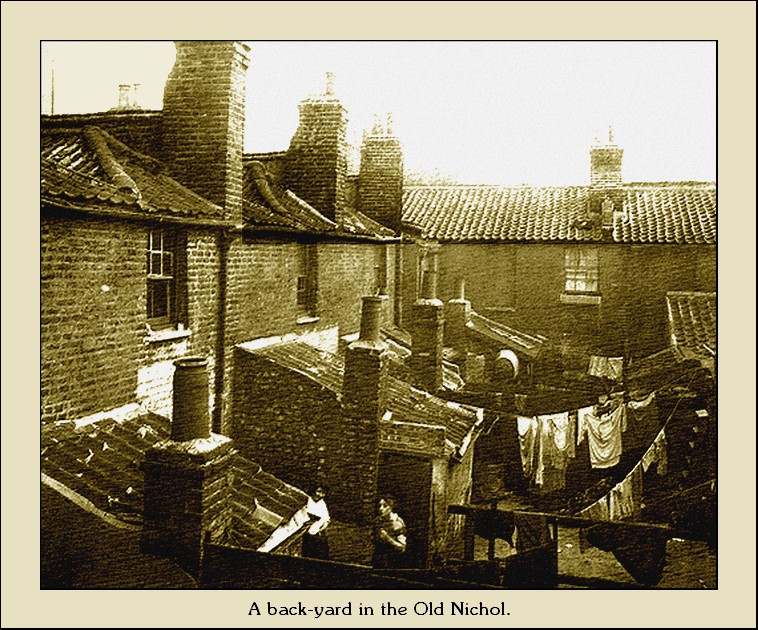

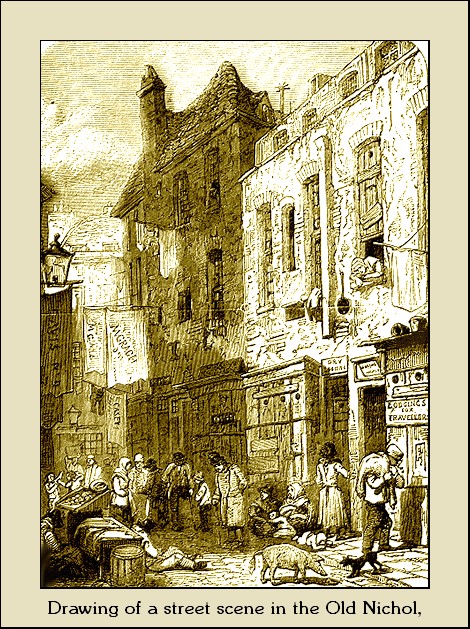

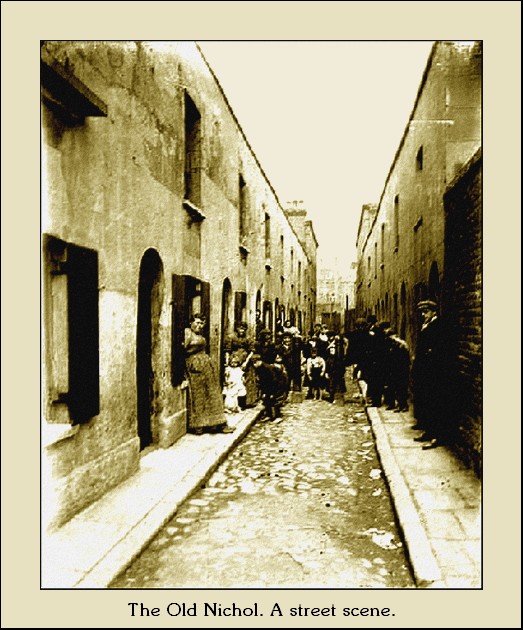

The Old Nichol was built around 1800 and comprised a labyrinth of thirty or so narrow streets and alleyways. Most of the area’s inhabitants were crammed into oppressive one-room flats with no sanitation or running water. The very bricks and mortar oozed with despair. To outsiders the streets of the Old Nichol were mysterious, threatening and laden with the threat of violence, but to the area’s residents its network of narrow streets provided a place of rapid escape and shelter from enemies, particularly the police.

The Old Nichol was built around 1800 and comprised a labyrinth of thirty or so narrow streets and alleyways. Most of the area’s inhabitants were crammed into oppressive one-room flats with no sanitation or running water. The very bricks and mortar oozed with despair. To outsiders the streets of the Old Nichol were mysterious, threatening and laden with the threat of violence, but to the area’s residents its network of narrow streets provided a place of rapid escape and shelter from enemies, particularly the police.

Morrison’s Jago reproduced the street-pattern of the Old Nichol, with only the street names changed. His narrative centres on one family, the Perrotts, who lived in a one-room lodging in a courtyard Morrison called Jago Court. In the original Old Nichol this was known as Orange Court and the writer described it as: ‘the inner hell of this awful place’.

A Child of the Jago explores the influence of a sense of place upon the human psyche. For Morrison the very geography of the streets of the Jago produces a certain mentality: just like the winding passageways of the slum its inhabitants are furtive, guarded, and secretive; they operate by their own rules and not those of the society outside their own narrow confines. Home to the people of the Jago comprises ‘foul rat runs, these alleys, not to be traversed by a stranger’.

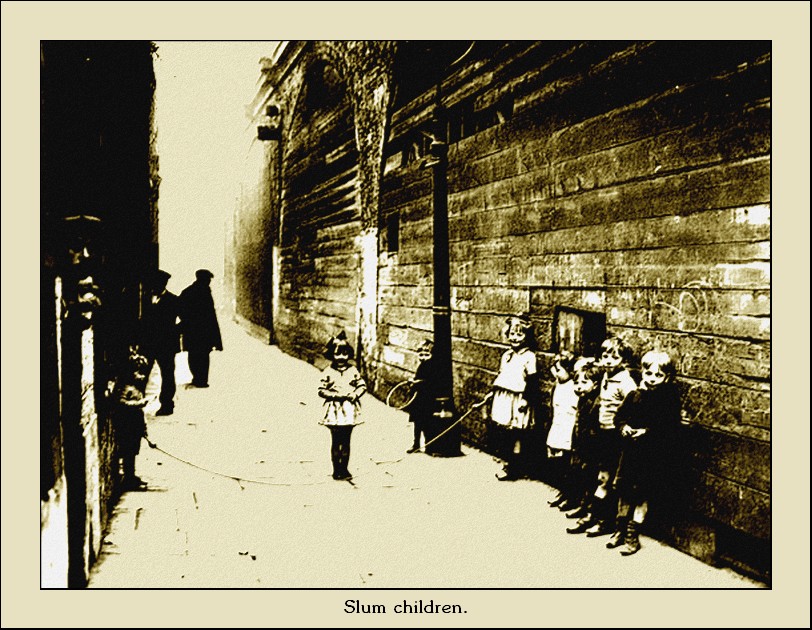

The child of the book’s title is Dicky Perrott, a lad of seven or eight when we first meet him. Dicky is presented as a decent boy at heart, but he becomes inexorably corrupted by the conditions in which he lives. There are only three ways out of the Jago one of its elderly residents, Old Beveridge, tells Dicky: the gaol, the gallows or to become one of the East End’s handful of gangster elite, the ‘high mobsmen’.

A Child of the Jago opens on an oppressively hot summer night when many of the residents of the Jago have chosen to sleep outdoors rather than within their airless dwellings. A stranger walking through the area is set upon, robbed and left unconscious in the street. Meanwhile young Dicky Perrott wanders home and finds his mother and baby sister trying to sleep. He finds nothing but a dry crust of bread to eat. Shortly afterwards his father, Josh Perrott, arrives home. Pretending to be asleep, Dicky notices that he is carrying a cosh matted with blood and hair.

The next day Dicky slips into a church mission event hoping to get free tea and cake. An opportunity presents itself for Dicky to steal a bishop’s gold watch and he does so, thinking of the food it will buy for his family. Pleased with himself, he returns home and hands it to his father, who promptly beats Dicky, but keeps the watch for himself.

The next day Dicky slips into a church mission event hoping to get free tea and cake. An opportunity presents itself for Dicky to steal a bishop’s gold watch and he does so, thinking of the food it will buy for his family. Pleased with himself, he returns home and hands it to his father, who promptly beats Dicky, but keeps the watch for himself.

Thus Dicky learns a harsh lesson about life in the Jago: any hint of sharing and generosity is regarded as weakness and only the cunning and devious will prosper:

Whoever was too young, too old or too weak to fight for it must keep what he had well hidden, in the Jago.

Dicky begins to steal regularly and falls in with the local fence, Aaron Weech, who encourages him to be ever bolder. He also learns to fight, joining in the feuds between the two clans that rule the Jago and on occasion getting involved in the pitched battles with the mob from the neighbouring slum, Dove Lane.

A Child of the Jago charts nine years of Dicky Perrott’s life in his East End slum, from the summer night when we first encounter him to the afternoon when his nemesis from Dove Street, Bobby Roper, pulls a blade on him in a street fight and the book reaches its inevitable conclusion. This is no Oliver Twist, despite there being several superficial similarities between the two books there is no happy ending in A Child of the Jago. Indeed, Morrison seems to suggest that there is no hope of redemption for any of the inhabitants of the Jago, a stance which drew widespread criticism at the time.

Morrison spent several months in the Old Nichol quietly conducting research for his book. He walked the area’s streets and talked to its people in the company of the local parish priest, Reverend Arthur Jay. Jay was the only outsider whose presence was tolerated by the inhabitants of the Old Nichol and he tried to improve the lot of the area’s young people by providing food and schooling.

Father Sturt, one of the few characters with any positive influence in A Child of the Jago, is based on Reverend Jay. Like Jay in real life, Father Sturt is the driving force behind having the slum gradually demolished and replaced by improved social housing. But just like Arthur Jay, Sturt was pessimistic that anything could be done to change the ways of the adults of the area: only with the younger children did he believe there was any hope of deliverance from the malign, corrupting influence of the Jago.

Sturt recognises something positive in Dicky Perrott and secures for him a job with a respectable local shopkeeper, Mr Grinder. Dicky works hard, learns quickly and things go well at first. But then Weech, having lost one of his best young thieves and fearful he will be exposed, feeds Grinder’s ear with poisonous rumours about Dicky and gets him sacked, pushing him back into the clutches of the Jago.

Most contemporary critics refused to accept that Morrison’s descriptions of the degradation and savagery of the Jago were based on fact. On the other hand, socialist reviewers, such as Robert Blatchford of The Clarion, said that Morrison played down some of the more appalling elements of life in the Jago: the brutal violence, sexual abuse, incest and prostitution.

Most contemporary critics refused to accept that Morrison’s descriptions of the degradation and savagery of the Jago were based on fact. On the other hand, socialist reviewers, such as Robert Blatchford of The Clarion, said that Morrison played down some of the more appalling elements of life in the Jago: the brutal violence, sexual abuse, incest and prostitution.

Modern-day historians accept that Morrison’s account, while it is bolted onto a fictional story, accurately reflects the reality of life in the East End of London at that time. Yet Morrison reserves the worst of his contempt for the high-minded philanthropists who tried to exert their influence on the Jago; only his friend Reverend Arthur Jay escapes this criticism. But Jay, like many at that time who had views that were otherwise socially progressive, also held some fundamentally reactionary ideas about the nature of those at the bottom of the social order.

Well-meaning people, even many who described themselves as socialists, despaired of the seeming unwillingness of the poor to improve themselves, to break free from the corrupting grip of places like the Old Nichol. Max Nordau’s twisting of Darwin’s work on evolution into notions of societal degeneration and coldly mad ideas such as eugenics were widely supported in the fin de siècle era.

Yet in the end it is the Jago that wins. Dicky Perrott embraces it and it breaks him, body and soul. To navigate the Jago’s labyrinthine streets, to have knowledge its ways, Morrison seems to say, is to have knowledge of evil.

Pingback: Past ghosts and future heroes – The Red Ink