That was when I was twenty, half my life ago, and a boy my age made the most politely democratic proposition I ever received: would I like to make a movie with him in the ruined hospital near my San Francisco home

A Field Guide to Getting Lost – Rebecca Solnit

For a short time in the mid-1980s I worked in the occupational therapy department of a very large psychiatric hospital in Wales; a vast, rambling Victorian Gothic building that glowered down from its hillside above the town. Some of the patients I met were very ill and needed medical care to help them overcome the worst of their symptoms. The biggest issue faced by most of the people I worked with, however, was helping them to deal with the effects of years and years of enforced institutionalisation; their need to learn how to live a life out in the community again.

Although the hospital formed only a short period of my working life, I often think about it and occasionally its corridors haunt my dreams. The hospital is empty now and, as far as I am aware, steadily falling into decay. All of its residents have gone. . . somewhere. But it still exerts its power over me and, no doubt, everyone else who came into contact with it.

I recall Iain Sinclair talking in an interview about the powerful life force that still resonates in many abandoned hospital buildings; echoes of the intense emotional drama that has taken place there: suffering, hope, despair, life and death. He commented on how artists and other creators will often choose to occupy such abandoned spaces for their work, as if seeking to tap into some vast reservoir of creative life energy. Perhaps that is why Rebecca Solnit and her friend found that their abandoned hospital in San Francisco served as such a powerful catalyst and backdrop for their film:

Its intricate vastness reminded me of all those Borges tales about labyrinths and endless libraries, and part of my premise was that the hospital was thought to be infinite, an interior without an outside.

A Field Guide to Getting Lost – Rebecca Solnit

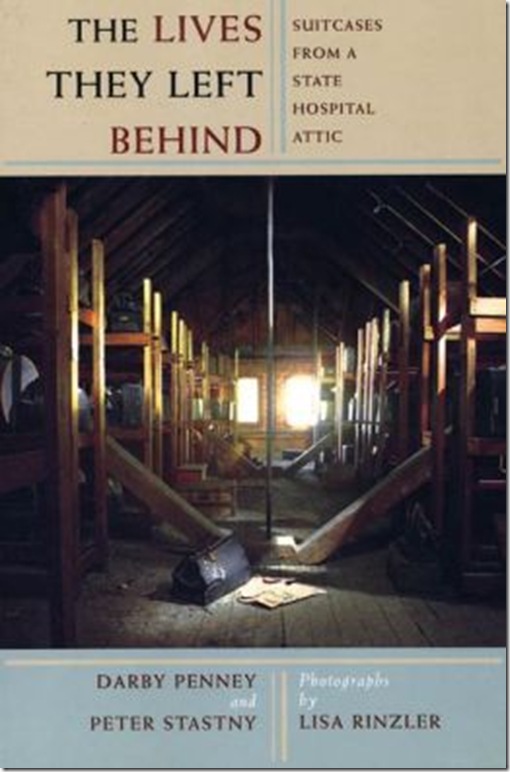

Darby Penney & Peter Stastney’s book is about such a place: an abandoned psychiatric hospital in New York State. Penney is a human rights activist and Stastney a psychiatrist and both were given access to Willard State Hospital to curate an attic full of property belonging to former patients. The Lives They Left Behind: Suitcases From a State Hospital Attic is the book that grew out of this project. Their aim was not to exploit this material for their own ends, nor was it to feed on the atmosphere of the place in a vicarious way. Instead they set out, with photographer Lisa Rinzler, to tell the stories of some of the former inmates of that institution, many of them now dead. They wished to give a voice to the voiceless, the forgotten.

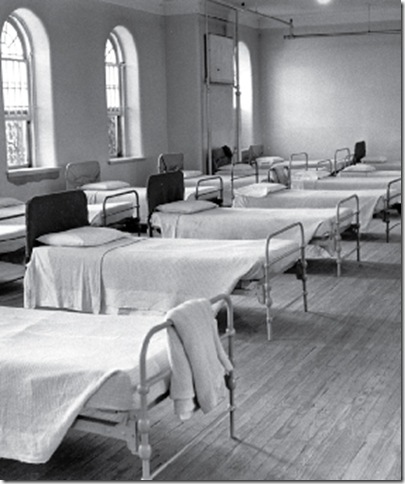

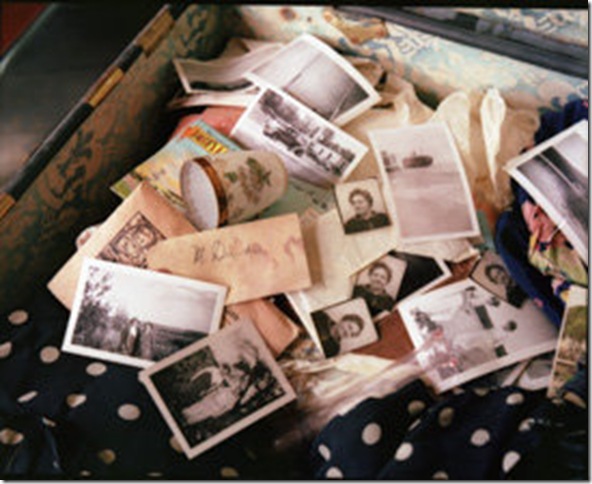

Penney and Stastney’s starting point was the large collection of suitcases stored in the hospital’s attic. Patients would arrive with cases stuffed not just with their clothes, but with a whole range of personal effects; items that represented who they were and the life they had led. But inmates were not allowed to have these cases with them on the ward, such fripperies were not deemed to be appropriate to institutional life, and so the cases were put into storage, in most cases for years, and too often for the rest of the patient’s life. Sadly, once someone entered Willard, they tended to remain there for the rest of their days.

Underlying this book is the story of how mental health was dealt with in the Western world over the course of much of the twentieth century. Mental hospitals operated not so much as places where distressed people could find refuge and receive help with their illness, but as institutions to remove people from society, often for life. In the United States in particular, notions of eugenics held sway for much of the century and the ‘insane’ and ‘mentally defective’ were in effect removed from the gene pool, at least for the duration of their breeding years.

The Lives They Left Behind: Suitcases From a State Hospital Attic tells the stories of ten inmates of Willard, stories illustrated by the contents of the suitcase belonging to each of them. But these were not ill people as we would understand the concept. Nor, in many cases, were they being helped with any therapeutic interventions we would recognise.

Lawrence Marek, for instance, spent over fifty years in Willard until his death in 1968 at the age of ninety. He was not mentally ill in the conventional sense of the word. As an immigrant from a small village in Austria he simply found himself culturally bewildered in the United States and, when he began to feel doubt about his long-held Christian faith, the whole framework of his life began to unravel.

Marek was clearly not insane, he was just profoundly distressed, but this was enough for the authorities to have him committed to Willard. He received no medical treatment at Willard but, as the years went by, it became his home until he reached the point where he did not want to leave. In fact, the institution came to rely on him because he became their unpaid grave-digger, a role he held for over thirty years. Marek’s brown leather suitcase, with the initials ‘L.M.’ etched onto it, held his pathetically small collection of personal items: clothes, shoes and shaving gear.

Another patient, Ethel Smalls, was admitted to Willard at the age of forty and remained there until she died at the age of eighty-three in 1973. Mrs Smalls had been subjected to a series of tragedies in a short period of time: both her infant children died in quick succession and then her father passed away with cancer. Soon after this her alcoholic husband, who had abused her for years, abandoned her and left her to struggle by on very little money. Not surprisingly, Mrs Smalls became depressed. But such was the attitude of the time to normal human responses to life’s traumas, particularly the responses of women, that Mrs Smalls was deemed to be insane and was admitted to Willard. Her suitcase tells the story of the little comforts she tried to hold on to in her tragic life: a family Bible, pictures of her children and, most heartbreaking of all, lovingly crafted home-made baby clothes.

Lawrence Marek and Ethel Smalls were just two of the 54,000 patients who passed through Willard State Hospital’s doors during its 126 years of operation. Some 18,000 of them died there and more than 5,000 are buried in the graveyard that was tended by Marek. Very few of these people had a severe mental illness. As Penney and Stastney put it:

The experiences and behaviours that caused someone to be sent to Willard ranged widely, from years of bothersome ‘agitation’ that was used to justify solitary confinement and physical restraint, to minor social nuisances and the inability to secure work.

The Lives They Left Behind: Suitcases From a State Hospital Attic tells just some of the human stories behind the statistics of the thousands of people who passed through Willard. Penney and Stastney build their narrative around the suitcases found in the hospital’s attic. Their work is moving and humane. The most haunting images, however, those that linger in one’s mind, come from the State archive pictures and those taken by Lisa Rinzler that are used to illustrate the text. Once one reads this book, Willard never quite leaves one’s consciousness.

* * *

The Lives They Left Behind: Suitcases From a State Hospital Attic by: Darby Penney and Peter Stastney; photographs by: Lisa Rinzler Bellevue Literary Press, New York, 2009

As a follow-up to Penney, Stastney and Rinzler’s work, the photographer Jon Crispin is systematically recording the Willard suitcases. His work in progress can be seen here:

http://joncrispin.wordpress.com/2011/03/18/willard-asylum-suitcase/

Thanks for pointing me towards this.

Dear Billy,

As you probably know Lawrence’s last name was Mocha. The OMH is against using real last names. We at the WCMP are trying to get that changed so we can memorialize Lawrence. We have a donor who wants to erect a memorial to him and we are being kept from doing this. There is legislation to release names to memorialize but it never gets to the floor for a vote. If you would like to join our effort check out our website.

Hi Colleen, Thank you for getting in touch. I wish you every success in your campaign to ensure that the 5,776 individuals are properly memorialized and remembered: willardcemeterymemorialproject.com