The sudden change of ambiance in a street within the space of a few meters; the evident division of a city into zones of distinct psychic atmospheres; the path of least resistance which is automatically followed in aimless strolls (and which has no relation to the physical contour of the ground); the appealing or repelling character of certain places – all this seems to be neglected.

Guy Debord: Introduction to a Critique of Urban Geography (1955)

When I was a child I began to construct a map of the small town in which I lived. It wasn’t a physical map, but one that I began to trace in my mind. And it was an experiential map: as I grew and became more familiar with my neighbourhood, as I expanded my horizons, so the map grew.

As a small child my map consisted of the houses nearby where the children with whom I played lived and the waste ground across the road where we acted out our games. Just around the corner was the sweet shop and chippie which both featured prominently on my map and, once I was allowed to walk to school with my mates and without my mum, around the age of five or six I seem to recall, my map expanded hugely to include the recreation ground, the park and other, less familiar streets.

As I grew older my personal map steadily expanded and I even began to grasp some notion of how my sleepy market town fitted into the wider world. But I never actually saw a real printed map of my town, at least not until I started secondary school.

I don’t think my experience is unique; all children map out their surroundings, pushing at the boundaries and conducting explorations. It’s a process engaged in at an individual level, but also a collective one; as children on our council estate we had our own names for many of the topographical features around us, names which were not familiar to most of the adults around us. We had our own folklore and mythology concerning certain locations; dire warnings about certain houses, lanes or woods.

In fact, researchers from the National Library of Australia have shown that there is a form of folklore which belongs exclusively to children. Child’s lore is different to folklore in that it is passed from one child to another, whereas folklore is transmitted by adults to children.

I have a lifelong love of maps. I find them useful for what they can do; a street map can help me find my way around somewhere unfamiliar and, as a regular hill-walker, I rely heavily on OS maps. But I also love maps as works of art, gorgeous colourful maps with exotic names and suggestions of strange landscapes. Judith Schalansky’s Atlas of Remote Islands: Fifty Islands I Have Not Visited and Never Will, for instance, is a masterpiece of lovingly created, hand-drawn maps.

Maps have never been so readily available, not just the traditional Ordnance Survey and A to Z variety, but maps on your computer, on your phone and in your car. Maps are everywhere. But what is a map? What does it tell us and who drew it? Do we have to accept the officially sanctioned version or, taking the lesson that childhood offers us, do we make a conscious decision to construct our own living maps?

The Situationist International was a disparate group of French intellectuals and dissidents who, in the 1950s, created a loosely-drawn school of thought that we now refer to as psychogeography. For me, psychogeography is an invaluable and radically different tool that we can engage to help us understand the social and geographical environment in which we live.

The city is a human-created environment as, indeed, are suburban and rural zones. The way in which we experience and react to these environments, however, is not neutral but it is conditioned and controlled by the prevailing drivers of our society. The legacy of Guy Debord and other pioneers of psychogeography is to suggest to us that there are ways in which we can expose and subvert this environmental manipulation and, in doing so, begin to exert some control over the way that we experience our streets.

Our experience of the city is increasingly characterised by prescription: zones for retail, business and housing are assigned at the planning stage and the routes that we walk, cycle or drive through the city are labelled and any deviation is discouraged. Even our mental image of the city is manipulated and boxed into a kind of restrictive functionality. Harry Beck’s iconic London Tube map, for instance, though a beautiful visual creation in itself, sacrifices the human and the whimsical in favour of the functional. For many of us this map is London, but it is a London where any form of wandering, exploring or even simply hanging around is discouraged in order to push us towards taking the quickest route from A to B.

Psychogeography’s most powerful tool for experiencing the city in an altogether different way is the dérive, or drift. A dérive involves the participants wandering through the city with no particular purpose or destination. But it is not an aimless walk; on a dérive our minds remains consciously engaged. And as we walk we remain open to the resonances that certain streets or buildings produce within our emotions and we note not just what we see, but the sounds and smells we encounter and the texture of the ground beneath our feet.

…the Situationists developed an armoury of confusing weapons intended constantly to provoke critical notice of the totality of lived experience and reverse the stultifying passivity of the spectacle. ‘Life can never be too disorientating,’ wrote Debord and Wolman, in support of which they described a friend’s experience wandering ‘through the Harz region of Germany while blindly following the directions of a map of London

Sadie Plant: The Most Radical Gesture: The Situationist International in a Postmodern Age (1992)

This is not so much a case of wandering without a map but, to return to our original theme, it is wandering in order to construct our own map. And, rather like the tale of the emperor’s new clothes, once we make a conscious effort to see through and beyond that which we are told we should see, we begin to develop a cognition that is, to a limited degree at least, free of societal orthodoxy. We develop a way of experiencing the city that is not defined by consumerism or the commodification of our relationships. To use the language of psychogeography, this is our détournment; the turning around of our consciousness.

But, in case this is all beginning to sound a little too earnest, remember that Debord characterised psychogeography as ‘playful reconstructive behaviour’ and that the whole process is about asserting the freedom to enjoy exploring our streets.

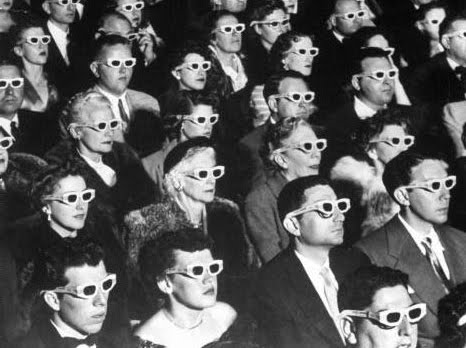

Image courtesy of Red & Black, Detroit

How do you experience the city without being affected by “consumerism or the commodification of our relationships?” Everything I see seems to revolve around capitalism and the spectacle. How does one find something on the derive that makes it different from a regular walk? What am I looking for, though I’m not really supposed to be looking for anything? I attempted to take a derive, but it felt like a regular walk.

Thanks.

Thanks Carly – you’ve raised a really incisive question and I’m not sure I have an answer to it, in fact I don’t think there is a complete answer. We live in a world dominated by global capitalism and our governments pander to the wishes of international brands and corporations and turn our cities into glorified shopping malls. You’re right to suggest that it’s impossible for us to step outside of the influence of this global system. I think it was Raymond Williams who said that the city is not just a place, but a form of consciousness, and it is to try to alter this consciousness, even if only fleetingly, that people calling themselves psychogeographers, deep topographers, flaneurs, or whatever, go in for the sorts of playful walking exercises you can read about on hundreds of blogs and websites. Maybe there’s a group or some like-minded individuals in the area where you live with whom you can explore this further? I’m sorry I don’t have a more complete answer, but I hope you’ll keep in touch with this blog.

Do you think there are shortcomings with psychogeography?I’m new to it and have been reading about how the derive is ultimately about trying to find something outside the spectacle, and there is focus on human becoming, but it doesn’t seem super realistic.

My view is that, although psychogeography’s most serious shortcoming as a methodology is its inexactitude, this also gives it a flexibility, which is its strength. Psychogeography is constantly able to morph and reinvent itself. Here is an interesting piece on this subject by Stewart Home: https://www.stewarthomesociety.org/sp/psycho.htm