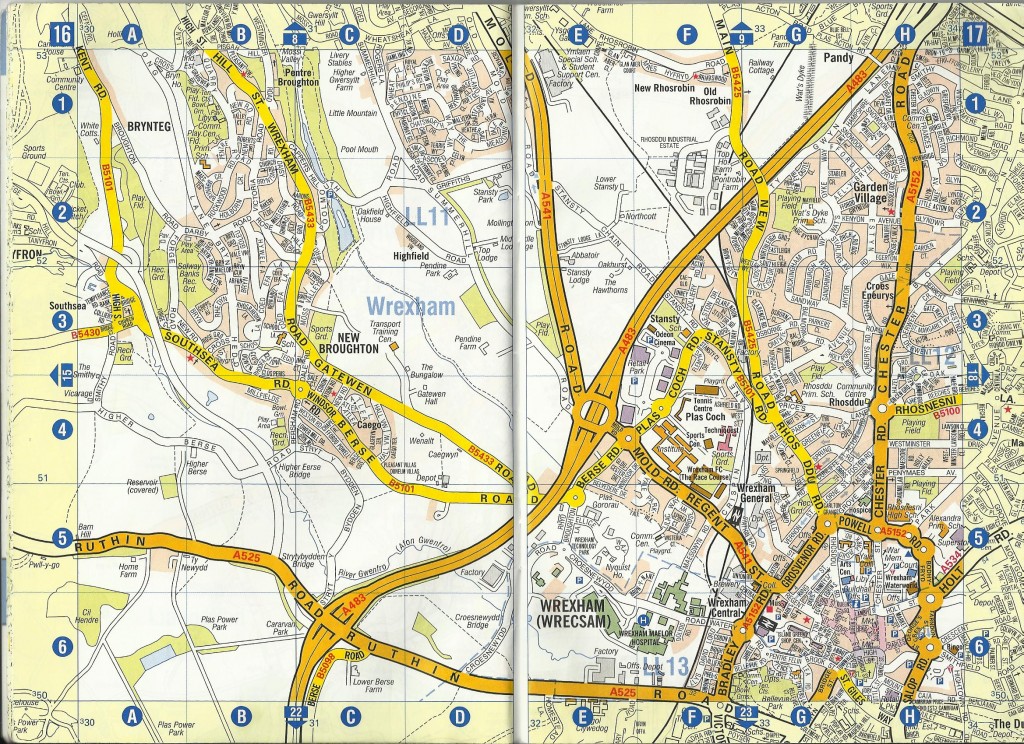

Dewdrop had called it a circumnavigation, but the reverence with which he handles the map this morning as he shows me our route suggests it’s something more akin to a pilgrimage for him. When he rang me last week he told me the plan was to walk the 1857 boundaries of the old Borough of Wrexham in North Wales. Dewdrop’s home town.

On the modern map it looks like a drunken circle, meandering vaguely clockwise from the north west of the borough and across to the east, turning south, then west, before returning to our starting point in the north west. A walk of just over nine miles. I remind Dewdrop of the mystical significance of circles; circles can unite and hold a number of elements together. But they can also form a knot, tying in accumulated memory and anchoring it to its rightful place in this world. Dewdrop sniffs dismissively.

He hands me the map and fiddles with his coat, desperately checking each of its pockets for something. Anything. I try to ignore him and, with my finger on the map, trace a clear western boundary formed by the line of the old Great Western Railway and, on the southern edge, another boundary formed by the River Clywedog. Dewdrop’s handwritten notes on the map promise old pubs and the husks of former breweries and mills; relics of bygone Brew Town, as Dewdrop calls Wrexham.

It’s a journey that regularly criss-crosses the serrated boundary between the Borough’s two medieval townships, Wrexham Abbot and Wrexham Regis. Which made me wonder if would there be any evidence of this municipal duality on the ground; a definable character to each township that is discernible in the local topography. And what of the zones of transition between the two?

We start our journey at the recreation ground in Garden Road. Dewdrop had been there waiting for me, leaning against the tubular steel frame of the swings, like some grotesque child, clothes too big for his body, the skin of his head too big for his skull. As we head down Garden Road we pass the Salvation Army Citadel, a stronghold of sobriety in a town awash with beer.

We cross into Cunliffe Street and skirt along Spring Road. In the eighteenth century this was the site of Brew Town’s pleasure grounds and numerous springs provided fresh, clear water: the basis of good beer. We move on to Price’s Lane, a busy cut-through between two main roads but once just a track leading to Walnut Farm. The farm is long-gone, but the old farm-house remains, latterly it was the Walnut Tree pub now closed. At the other end of the lane we reach the site of another farmstead, Croes Eneurys Farm, its fields sweeping up to a hilltop where the farmhouse once guarded the road to Chester.

Dewdrop points out the allotments across the field and remarks on how it strikes him that so much of this land along the boundary of the old borough is, or once was, municipally owned. Across Chester Road we come to The Four Dogs, a 1970s pub named after the symbol of the old Acton estate, one-time owners of much of the land along the northern fringe of Brew Town. All that remains of the house is a monumental stone gateway next to the pub. On top of the gateway sit four dogs, two on each side, facing away from each other: Egyptian dog gods. The Jeffreys family, owners of the Acton estate, are long gone. Their most notorious member, Judge Jeffreys, the hanging judge, surely the least lamented. His family’s bad fortune and subsequent penury perhaps the price they all had to pay for his sins.

Along Box Lane we come to Acton Park primary school, its original building once a diamond-polishing works, leased from the Acton estate just after the Great War by a Belgian entrepreneur. Mineral wealth from Africa; a scheme to get rich quick, but in reality nothing more than vampire economics. Another failed endeavour; the luck of the Jeffreys. When the estate finally went bust it passed into municipal hands and, between the two wars, much of Acton was transformed by the Borough Council into another kind of estate; Brew Town’s first council housing. Semi-detached houses, pleasantly laid out in closes and crescents, each house with its own generous portion of garden.

We reach the Queens Park Estate, hastily renamed Caia Park after the race riots of 2003. Built in the days of old Labour, this huge council estate is a Brew Town dream that died under New Labour. There is very real deprivation here – the estate is supported by the Welsh government through its Communities First programme in recognition of this. And yet, just across the Holt Road is open, rolling countryside and several prosperous farms.

As we walk through the estate, Dewdrop tells me that the disgraced US president, Richard Nixon, was able to trace his roots back to the area. Nixon was apparently descended on his mother’s side from the Puleston family who lived at a country house called Hafod y Wern on land that now forms part of the Caia estate.

Abenbury Road takes us through to King’s Mills – once part of Wrexham Regis and the site of Brew Town’s corn milling industry, utilising water power from the River Clywedog. It’s now an industrial museum, flanked by two pubs. Dewdrop mentions he used to drink in one of them, the Red Lion. He’s off the drink now and I’ve heard he’s painting again, though I’ve not seen any of his work for years.

Wrexham Regis represents the lands formerly belonging to the Crown, mainly in the northern part of the town. The lands of Wrexham Abbot, on the other hand, belonged to the Church for hundreds of years. But when Valle Crucis Abbey was dissolved in 1537, the the lands passed to the Crown. King’s Mills is still something of a front-line between the two zones of influence, Church and Crown,

Skirting past the old mill, we clamber under the bridge and out onto the water meadows of the western edge of the Erddig estate.

Erddig, the eighteenth century house and over a thousand acres of parkland, was donated to the National Trust by the Yorke family in the 1970s. Philip Yorke, the last surviving member of the family, couldn’t afford the upkeep of the house and wanted it preserved for the nation. Dewdrop, slightly more relaxed after his beer, reminds me that the National Trust, those guardians of our heritage, recently tried to sell off a significant chunk of the parkland for executive homes. The Trust membership he concludes, fortunately, voted against the proposal and it was dropped. For now.

We follow the river to Felin Puleston, the site of another mill, and pass under the main road and out of the Erddig estate. Our walk now skirts the GWR railway track, a straight mile or so to the General Station; apparently the Victorians obliterated a long section of Wat’s Dyke to creatre this stretch of line.

We trudge on past the hospital, the station and through a building supplies company’s yard until we reach our starting point once more; completing the circle, closing it off. Symbolically we have united Abbot and Regis and salved the town’s ancient wounds.

Map courtesy of Geographers‘ A-Z Map Company Limited

Pictures by Anthony ‘Dewdrop’ Evans

given me the idea to walk my towns municipal boundary, as on an old map and document my findings.

Worth a try, I would say.