What is psychogeography, anyway? My understanding of the concept is three-fold: it is a theory, a practice and a body of evidence. The most interesting of these, for me, is the body of evidence: the books, works of art and reportage that enable us to understand and engage with the social and geographical environment in which we live. Thus, at Psychogeographic Review I write about the novels, poems, maps, photographs, paintings, films and music that help us to construct a living map of the places where humans live.

But it’s still important to acknowledge that there is a set of theories underpinning this approach to how we interpret the world around us. I’m sure others can explain this more eloquently than me but, basically, the term ‘psychogeography’ was first coined by Guy Debord and the Situationist International in the 1950s. Debord and his associates were a disparate group of French intellectuals and dissidents who highlighted the fact that the city is a human-created environment. The way in which we experience and react to these environments, they argued, is not neutral but is conditioned and controlled by the prevailing drivers of our society.

As the Situationists were essentially Marxists, albeit maverick Marxists of a more libertarian persuasion, they identified capitalism as the force which coloured our view of the world. Everything in human society, all the ways in which we experience the world, is subject to a process of commodification by the prevailing system. So how do we get out of this bind where even the ways in which protest against the control of the system are absorbed by it and turned back on us to tighten its grip?

Psychogeography’s most powerful tool for experiencing the city in another way is the dérive, or drift. A dérive involves the participants in wandering through the city with no particular purpose or destination. But it is not an aimless walk; on a dérive our minds remains consciously engaged. And as we walk we remain open to the resonances that certain streets or buildings produce within our emotions and we note not just what we see, but the sounds and smells we encounter and the texture of the ground beneath our feet.

But the dérive isn’t something new. The literary character of the Parisian flâneur, the casual wanderer of the streets, was created by Baudelaire in the nineteenth century; but the idea goes back even further to Defoe, Blake, De Quincey and beyond. More recently a host of writers, from Peter Ackroyd to Iain Sinclair, have written about our experience of ‘place’. Invariably these are places on the liminal margins of our cities that the writers encounter on foot.

For me the exciting element that contemporary writers, such as Sonia Overall, add to ‘traditional’ psychogeography, if using that word is not too much of an oxymoron, is a heady seasoning of myth, history, topographical resonance, popular culture and occult-like phenomena. There is also a lot of personal disclosure in modern psychogeography: ‘this is me in the landscape and this is the landscape in me’. The following is my personal and very subjective list of some of the books that have informed this discussion in 2022.

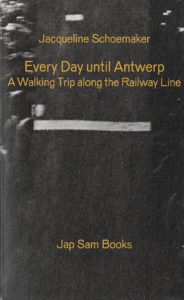

Every Day until Antwerp: A Walking Trip along the Railway Line by Jacqueline Schoemaker

Every Day until Antwerp is an account of a journey on foot that Schoemaker made in the summer of 2012, just before the old inter-city line was closed. Her plan was to walk the 150+ km between the two cities, shadowing as closely as she could the route of the railway line. She thought she knew this route well, having made the journey by train on many occasions. But, reflected Schoemaker while she planned this journey, her perception of the route was limited to the view from the train window. She had been a passive observer catching fleeting glimpses of the landscape rather than actually experiencing it by becoming a part of it. As we follow her journey, the repetitive nature of the landscape becomes apparent: various combinations of road, railway, cycle path, farm, village and industrial come into view, seemingly without end. In between these features in the landscape, however, are spaces that seem to belong to no one and have no particular utility. Schoemaker reclaims these liminal places; she humanizes them by using them as places to rest, wash or answer her calls of nature. Along the way she meets people who are kind and friendly. Most, however, ignore her, giving no more than a quizzical glance at this strange woman pulling along a shopping trolley.

summer of 2012, just before the old inter-city line was closed. Her plan was to walk the 150+ km between the two cities, shadowing as closely as she could the route of the railway line. She thought she knew this route well, having made the journey by train on many occasions. But, reflected Schoemaker while she planned this journey, her perception of the route was limited to the view from the train window. She had been a passive observer catching fleeting glimpses of the landscape rather than actually experiencing it by becoming a part of it. As we follow her journey, the repetitive nature of the landscape becomes apparent: various combinations of road, railway, cycle path, farm, village and industrial come into view, seemingly without end. In between these features in the landscape, however, are spaces that seem to belong to no one and have no particular utility. Schoemaker reclaims these liminal places; she humanizes them by using them as places to rest, wash or answer her calls of nature. Along the way she meets people who are kind and friendly. Most, however, ignore her, giving no more than a quizzical glance at this strange woman pulling along a shopping trolley.

In the Pines by Paul Scraton and Eymelt Sehmer

With In the Pines Paul Scraton presents us with a strange, brooding collection of literary fragments. They are drawn together by an unnamed narrator and haunted by the ever-present forest that dominates the narrator’s life. We are not given the name of the forest, nor is it made clear in what country Scraton’s stories unfold. Neither are we given the name of the narrator and even their gender is left unclear. Integral to the book is the black and white photography of Eymelt Sehmer. She uses a photographic technique called the collodion wet plate process. This requires a black tin plate to be coated, sensitized, exposed and developed in the space of about fifteen minutes. The viewpoint of the central narrative switches regularly from the first person to the third, often within the same fragment. The only constant is the forest; its presence underpins everything.

With In the Pines Paul Scraton presents us with a strange, brooding collection of literary fragments. They are drawn together by an unnamed narrator and haunted by the ever-present forest that dominates the narrator’s life. We are not given the name of the forest, nor is it made clear in what country Scraton’s stories unfold. Neither are we given the name of the narrator and even their gender is left unclear. Integral to the book is the black and white photography of Eymelt Sehmer. She uses a photographic technique called the collodion wet plate process. This requires a black tin plate to be coated, sensitized, exposed and developed in the space of about fifteen minutes. The viewpoint of the central narrative switches regularly from the first person to the third, often within the same fragment. The only constant is the forest; its presence underpins everything.

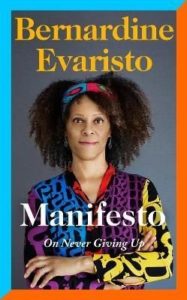

Manifesto: On Never Giving Up by Bernardine Evaristo

Manifesto is part memoir and part handbook providing insights into Bernardine Evaristo’s creative process. This inspirational work tells the story of her life and the influences, attitudes and ways of working that led to her eventual success as a writer. Recognition was a long time in coming and winning the Booker prize at the age of 60 was testimony of Evaristo’s commitment to never giving up. In 2019 Evaristo won the Booker prize for fiction for her novel Girl, Woman, Other and now combines her own creative work with teaching and encouraging others. Despite her current status as part of the nation’s literary establishment, Bernardine Evaristo has spent most of her career as an outsider. Her race, gender, sexuality and class all provided sticks with which she was regularly beaten, But, rather than cave-in to rejection and scorn, Evaristo used it to make herself stronger and more resilient. Manifesto is a portrait of a woman who has dedicated her life to breaking down barriers and bringing people together.

creative process. This inspirational work tells the story of her life and the influences, attitudes and ways of working that led to her eventual success as a writer. Recognition was a long time in coming and winning the Booker prize at the age of 60 was testimony of Evaristo’s commitment to never giving up. In 2019 Evaristo won the Booker prize for fiction for her novel Girl, Woman, Other and now combines her own creative work with teaching and encouraging others. Despite her current status as part of the nation’s literary establishment, Bernardine Evaristo has spent most of her career as an outsider. Her race, gender, sexuality and class all provided sticks with which she was regularly beaten, But, rather than cave-in to rejection and scorn, Evaristo used it to make herself stronger and more resilient. Manifesto is a portrait of a woman who has dedicated her life to breaking down barriers and bringing people together.

Shalimar by Davina Quinlivan

Davina Quinlivan is a writer and lecturer whose background embraces a rich cultural heritage. Her extended family melds together strands from Burma, India, Ireland, Germany, Portugal and the Shan hill people of South-East Asia. Shalimar explores the history of this family, comprising forebears from Europe and Asia, and takes us through to Quinlivan’s present life in rural Devon with her partner and children. At the heart of the book, ever present even after his death, is the writer’s father. At a social and political level Shalimar is about race, colonialism and migration. At a more personal level it is an exploration of the meaning of family and home. Like the rest of us, Quinlivan’s life is an outflowing of the influences of her family history. Unlike most of us, she is able to express this profound truth in achingly beautiful prose.

Davina Quinlivan is a writer and lecturer whose background embraces a rich cultural heritage. Her extended family melds together strands from Burma, India, Ireland, Germany, Portugal and the Shan hill people of South-East Asia. Shalimar explores the history of this family, comprising forebears from Europe and Asia, and takes us through to Quinlivan’s present life in rural Devon with her partner and children. At the heart of the book, ever present even after his death, is the writer’s father. At a social and political level Shalimar is about race, colonialism and migration. At a more personal level it is an exploration of the meaning of family and home. Like the rest of us, Quinlivan’s life is an outflowing of the influences of her family history. Unlike most of us, she is able to express this profound truth in achingly beautiful prose.

Nettles by Adam Scovell

Nettles opens with a harrowing account of a boy’s first day at secondary school and the campaign of bullying to which he was subjected. The bully has no name and is simply referred to as He and Him. He is the leader of a gang of fawning acolytes and presents as an almost mythical figure, one in possession of great physical strength and animal cunning. At its heart, Nettles is a lament for the loss of childhood innocence and happiness. But the boy is not without his allies; the marsh and the motorway bridge just behind his school provide a place of refuge, somewhere to hide from the attentions of the bully during lunchtime and breaks. But it offers more than just a place of physical safety, the marsh offers a kind of spiritual sanctuary too. It speaks to him, it encourages him to endure and promises that in the end he will prevail and will defeat the bully for good: ‘He will die.’

campaign of bullying to which he was subjected. The bully has no name and is simply referred to as He and Him. He is the leader of a gang of fawning acolytes and presents as an almost mythical figure, one in possession of great physical strength and animal cunning. At its heart, Nettles is a lament for the loss of childhood innocence and happiness. But the boy is not without his allies; the marsh and the motorway bridge just behind his school provide a place of refuge, somewhere to hide from the attentions of the bully during lunchtime and breaks. But it offers more than just a place of physical safety, the marsh offers a kind of spiritual sanctuary too. It speaks to him, it encourages him to endure and promises that in the end he will prevail and will defeat the bully for good: ‘He will die.’

Robinson in Chronostasis by Sam Jenks with Koji Tsukada and Dan Jackson

Opening the pages of Robinson in Chronostasis is like setting out on a psychogeographic dérive. You do not know where the journey will take you nor what you will see along the way. Discovering the route through this work is satisfyingly unclear. You can follow Sam Jenks’s narrative, a small block of text on each page, or perhaps read the story told by Koji Tsukada’s photographs, starting and finishing the sequence wherever you choose. Alternatively you can be drawn along by the looping threads, the puzzling symbols, of Dan Jackson’s graphic designs. Jenks’s narrative takes the reader on a journey through the streets of Bath, mixing past and present, memory and sensation. In doing so he seems to raise questions about our perception of time and the nature of story-telling and memory. The answers, if there are any, are left for the reader to decide. Robinson, of course, is the companion of the narrator in Patrick Keiller’s Robinson films. He/she/they is an almost mythical figure, the archetypal flâneur. Jenks’s Robinson stalks a trail left by the artist Koji Tsukada, his commentary mixing past, present and conjecture.

Opening the pages of Robinson in Chronostasis is like setting out on a psychogeographic dérive. You do not know where the journey will take you nor what you will see along the way. Discovering the route through this work is satisfyingly unclear. You can follow Sam Jenks’s narrative, a small block of text on each page, or perhaps read the story told by Koji Tsukada’s photographs, starting and finishing the sequence wherever you choose. Alternatively you can be drawn along by the looping threads, the puzzling symbols, of Dan Jackson’s graphic designs. Jenks’s narrative takes the reader on a journey through the streets of Bath, mixing past and present, memory and sensation. In doing so he seems to raise questions about our perception of time and the nature of story-telling and memory. The answers, if there are any, are left for the reader to decide. Robinson, of course, is the companion of the narrator in Patrick Keiller’s Robinson films. He/she/they is an almost mythical figure, the archetypal flâneur. Jenks’s Robinson stalks a trail left by the artist Koji Tsukada, his commentary mixing past, present and conjecture.

Terminal Zones by Gareth E Rees

Each short story in this new collection by Gareth E Rees is set against the background of the global climate crisis. In the Britain of the near future the ice caps are melting, our coastline is eroding, the land is poisoned and our forests and heathlands are burning. In the best of these ten stories Rees’ prose, quite appropriately, sizzles. Though it has to be said that the quality varies and some of the tales are more successful than others. But throughout Rees writes with passion and verve. But this is no scientific treatise nor work of polemic. Rees concentrates on what he writes about best, which is people. Throughout this collection ordinary people are caught up in extraordinary events. All of the usual Gareth Rees tropes are here: motorways, pylons, car parks, retail parks and abandoned industrial sites. The thing that is new, that is experimental, is the range of characters Rees creates, a whole world of them.

the global climate crisis. In the Britain of the near future the ice caps are melting, our coastline is eroding, the land is poisoned and our forests and heathlands are burning. In the best of these ten stories Rees’ prose, quite appropriately, sizzles. Though it has to be said that the quality varies and some of the tales are more successful than others. But throughout Rees writes with passion and verve. But this is no scientific treatise nor work of polemic. Rees concentrates on what he writes about best, which is people. Throughout this collection ordinary people are caught up in extraordinary events. All of the usual Gareth Rees tropes are here: motorways, pylons, car parks, retail parks and abandoned industrial sites. The thing that is new, that is experimental, is the range of characters Rees creates, a whole world of them.

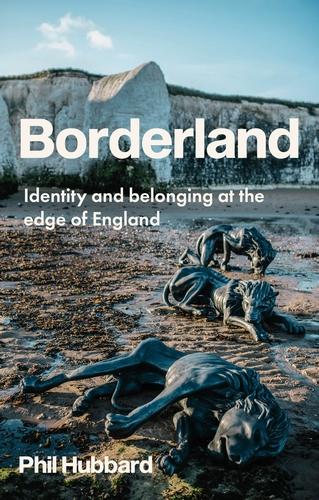

Borderland: Identity and belonging at the edge of England by Phil Hubbard

Borderland was born out of a series of journeys made on foot by Phil Hubbard in 2019. A native of Kent now based elsewhere, Hubbard wanted to explore the county’s coastline from the Thames and the North Kent Marshes down to Dungeness and the Sussex border in the south. It is a coastline configured by Britain’s relationship with continental Europe and is subject to the ebb and flow of relations between the two sides of the Channel; periods of antagonism followed by periods of ‘entente cordiale’ and closer ties. Hubbrd highlights how, during times of strained relationships such as the present, Kent’s coast is presented by some as the imagined battleground where a number of national myths are played out. Borderland is a hugely engaging read and offers some profound insights into the past and present of Kent’s coastline and, by extension, of England as a whole. Hubbard examines the myths we summon up to explain our national past together with the malleability of memory and how some will seek to exploit that.

Borderland was born out of a series of journeys made on foot by Phil Hubbard in 2019. A native of Kent now based elsewhere, Hubbard wanted to explore the county’s coastline from the Thames and the North Kent Marshes down to Dungeness and the Sussex border in the south. It is a coastline configured by Britain’s relationship with continental Europe and is subject to the ebb and flow of relations between the two sides of the Channel; periods of antagonism followed by periods of ‘entente cordiale’ and closer ties. Hubbrd highlights how, during times of strained relationships such as the present, Kent’s coast is presented by some as the imagined battleground where a number of national myths are played out. Borderland is a hugely engaging read and offers some profound insights into the past and present of Kent’s coastline and, by extension, of England as a whole. Hubbard examines the myths we summon up to explain our national past together with the malleability of memory and how some will seek to exploit that.

The Half-Life of Snails by Philippa Holloway

The Half-Life of Snails is a novel permeated by a sense of place. Philippa Holloway examines the influence of place upon the lives of the people who inhabit two landscapes, two separate places linked by a single catastrophe that occurred several decades before, but the resonances of which linger on. The Half-Life of Snails achieves a powerful evocation of both the north coast of Ynys Môn and the exclusion zone around Chernobyl. Holloway conducted extensive field research in Ukraine while she was planning this book and her descriptions of ‘the zone’ have a palpable intensity. This is a landscape defined by absence. But the empty villages and farmsteads are, nonetheless, peopled by the echoes, the ghosts of those who once lived there. It is, in a very real sense, a haunted place.

examines the influence of place upon the lives of the people who inhabit two landscapes, two separate places linked by a single catastrophe that occurred several decades before, but the resonances of which linger on. The Half-Life of Snails achieves a powerful evocation of both the north coast of Ynys Môn and the exclusion zone around Chernobyl. Holloway conducted extensive field research in Ukraine while she was planning this book and her descriptions of ‘the zone’ have a palpable intensity. This is a landscape defined by absence. But the empty villages and farmsteads are, nonetheless, peopled by the echoes, the ghosts of those who once lived there. It is, in a very real sense, a haunted place.

The object we call a book is not the real book, but its seed or potential, like a music score. It exists fully only in the act of being read; and its real home is inside the head of the reader, where the seed germinates, the symphony resounds.

Rebecca Solnit, from a talk given at Novato Public Library, California

Like this:

Like Loading...

Lionel Thomas Caswall Rolt was born in Chester in 1910. A prolific writer, he specialised in biographies of some of the major figures in British civil engineering, most notably Brunel and Telford. He is also regarded as one of the pioneers of the leisure cruising industry on Britain’s inland waterways, and was an enthusiast for vintage cars and heritage railways. He played a pioneering role in both the canal and railway preservation movements. Rolt died in Gloucestershire in 1974.

Lionel Thomas Caswall Rolt was born in Chester in 1910. A prolific writer, he specialised in biographies of some of the major figures in British civil engineering, most notably Brunel and Telford. He is also regarded as one of the pioneers of the leisure cruising industry on Britain’s inland waterways, and was an enthusiast for vintage cars and heritage railways. He played a pioneering role in both the canal and railway preservation movements. Rolt died in Gloucestershire in 1974.

Pete Evans is a writer and tour guide based in north-east Wales. He is the author The Holy Dee and leads walking trips.

Pete Evans is a writer and tour guide based in north-east Wales. He is the author The Holy Dee and leads walking trips.

Peter Finch is a poet, writer, performer, walker and literary entrepreneur living in Cardiff. He has been a publisher, organisation manager, periodical editor, event organiser, literary agent and literary promoter. He was at the forefront of the UK’s small press revolution in the 60s and the 70s with his magazine Second Aeon and pioneered performance poetry in Wales during the 1980s. From 1974 to 1995 he ran the Oriel Bookshop in Cardiff. From 1996 to 2011 he was Chief Executive of Yr Academi Gymreig / The Welsh Academy, an organisation which was later rebranded as Literature Wales. He specialises in books about the Welsh capital including the successful Real Cardiff series (4 volumes), Edging the Estuary and The Roots of Rock From Cardiff to Mississippi and Back. His latest books written alongside the work of photographer John Briggs are Walking the Valleys and Walking Cardiff.

Peter Finch is a poet, writer, performer, walker and literary entrepreneur living in Cardiff. He has been a publisher, organisation manager, periodical editor, event organiser, literary agent and literary promoter. He was at the forefront of the UK’s small press revolution in the 60s and the 70s with his magazine Second Aeon and pioneered performance poetry in Wales during the 1980s. From 1974 to 1995 he ran the Oriel Bookshop in Cardiff. From 1996 to 2011 he was Chief Executive of Yr Academi Gymreig / The Welsh Academy, an organisation which was later rebranded as Literature Wales. He specialises in books about the Welsh capital including the successful Real Cardiff series (4 volumes), Edging the Estuary and The Roots of Rock From Cardiff to Mississippi and Back. His latest books written alongside the work of photographer John Briggs are Walking the Valleys and Walking Cardiff.